Essays, Part 2

• Places of Individuality in Chinese Cinema at Berlinale 2020

By Maja Korbecka

• The True Colors of Latin American Tricksters

By Rodrigo Garay

• Transcending the Race Barrier

By Sadia Khalid

• New Life Rising From the Deep

By Savina Petkova

Places of Individuality in Chinese Cinema at Berlinale 2020

By Maja Korbecka

Conversations around discourse and dialogue in Chinese cinema were featured prominently at this year’s Berlinale.

For the last several years, Chinese films have been a mainstay in the Berlinale’s programming. Chosen filmmakers such as Wang Quan’an, Lou Ye, or Zhang Yimou were members of the “Berlinale family” – a term often used by former director Dieter Kosslick to refer to auteurs whose films were consistently invited. The new festival team headed by Mariette Rissenbeek and Carlo Chatrian has put more focus on discourse and dialogue highlighted especially in this year’s On Transmission series. However, the conversation exceeds the section’s frames and permeates the whole program. If one looks for striking contrasts and surprising similarities, they certainly can be found in two Chinese selections, which are the only contemporary fiction films from mainland China in the 2020 program.

Both films are also linked to the figure of Jia Zhangke, reflecting various aspects of his relationship to the idea of Chinese cinema: its audience, cinematic image of the nation, filmmakers who shape it. Jia was one of the seven directors invited to bring one of their peers to the Berlinale and engage in dialogue about cinematic art accompanied by two film screenings: a work of their own and of the guest they have chosen. In the On Transmission section, Jia Zhangke selected Crossing the Border (Guo Zhao Guan, 2018) a feel-good family road movie directed by Huo Meng. This choice might reflect his desire to support independent filmmakers in their pursuit to connect to the broad Chinese audience. In the Forum section, The Calming (Ping jing, 2020) a minimalist arthouse pan-Asian production directed by Song Fang, features Jia as a producer. It reveals his ongoing support of individualist filmmaking in China that chooses to ignore market and audience expectations.

The Calming and Crossing the Border are very personal projects, written and directed by their respective authors and connected to their personal backgrounds in China. However, despite having a Chinese director and producer, and being mostly shot in China, The Calming is not labeled as a film from the People’s Republic of China in the program. Is there something that makes The Calming less officially representative for China than Crossing the Border? Both films have several elements in common: themes of travel, mobility, and family. However, the difference between the two titles is much more visible in many elements of the narrative: location, character design, language, mode of storytelling. The contrast is connected to the unending divide in Chinese philosophical thought and ways of seeing the world: one that is endorsed by the government, the other treated as an uncomfortable anomaly. A comparison of the two films’ narrative elements will shed light on their strategic location in the festival program as well as within Chinese cinema.

Crossing the Border recounts a journey through Henan, director Huo Meng’s home province. Starting from Yuanma village, the main characters drive a slow farm truck to visit an old friend on the distant western border of the region. The experience of rural provincialism is deeply ingrained in the film, celebrating a kind of diversity strictly within the national frame. The Calming, on the other hand, takes place in Tokyo, Niigata, Beijing, Nanjing, and Hong Kong. The travel between Japan and China connects the film to a transnational paradigm, reminiscent of the idea of pan-Asian cinema prominent in the 2000s.

The increased mobility is also connected to the main character’s identity, an upper-middle-class woman filmmaker whose exploration of space and environment is not marked by national borders. Her privilege is reflected through professional, educational, and social capital that allows her identity to become more fluid through the experiences of international travels and friendships. When asked about what it means for her to be Chinese, writer-director Song Fang stated that she is more interested in the individual experience, while rigid and inflexible terms such as nationality are secondary. The main character in The Calming serves as her alter ego, both are well-rounded citizens of the world but admit that the Chinese language and culture filter their ways of seeing the world.

The protagonists in Crossing the Border are the stark opposite. The film’s elderly farmer and his grandson experience limited mobility. They are left behind by working-age family members who have joined the urban lower class. The film tackles the phenomenon of massive internal economic migration and its extreme demographic effects on the countryside that is inhabited mostly by elderly people and their grandchildren. Crossing the Border reflects the state of Chinese society more explicitly and comprehensively than The Calming, which focuses on personal matters and is largely disconnected from social issues.

The differences between the films continue in their use of language. In The Calming, the main character shifts smoothly between Mandarin, English, and Jiangsu dialect, indicating her ease as a cosmopolitan. Her language abilities are one of the benefits of her education and access to resources. In Crossing the Border, the grandfather strictly speaks the regional Henan dialect while his grandson uses national standard Mandarin. Their communication reflects gaps in generation, education, and history. While they can’t speak each other’s language, they are able to devise a practical way to understand each other. Language abilities are acquired through informal learning that meets the necessities of everyday life.

When it comes to narrative style, Crossing the Border fulfills the state-approved ideology, presenting an exemplary Chinese man who remains very trustful and good-natured despite difficult experiences of Chinese history, as if the Cultural Revolution did not traumatize him at all. It could be that such idealization is informed by the filmmaker’s longing for his grandfather, who was a motivation for making the film. The cinematic space is extremely clean and polished as if dirt was cast out from the countryside. There is a different kind of sterility in The Calming. The visual style is minimalist, colors are toned down, cinematic space is very ascetic, the camera often remains static, centered on the protagonist’s face, her figure, and the way she interacts with the environment. All these factors reflect the main character’s self-imposed isolation from society and desire to come closer to nature, however, the pursuit might be after its idealized depiction. The shared idealization could be grounded in the filmmaker’s cultural position as the university-educated privileged generation, whose youth coincided with the reform period when more and more opportunities emerged to study and capitalize on the opening market.

Both films represent two extremes in Chinese philosophical thought that continue to guide the ways people in China interact with each other and the environment. Crossing the Border is permeated with a Confucian point of view. The focus on family, filial piety, social roles, and the attached responsibilities, the pursuit of harmonious coexistence visibly drives the narrative. It is also the reason why the film complies with the national agenda, since Confucianism enjoys an unexpected renaissance, becoming a useful tool of soft power as orchestrated by the government. The Calming, on the other hand, is closely connected to Taoist perspective and values: withdrawal from society, reconnecting with nature, life in isolation, focus on private and personal instead of public and collective that renders such attitudes suspicious from the government’s point of view, regardless of the period in Chinese history. Taoism had always existed on the margins of Chinese society but its importance cannot be underestimated.

While a transnational cinema paradigm and Taoist undertones might mark The Calming as less officially representative for China, it does not fully answer the question of why the film’s country of production is left blank. Jia Zhangke concluded his 2020 Berlinale Talents masterclass expressing hope that the future of Chinese cinema will no longer be marked by traumatic generational experiences and that filmmakers will finally be able to move on to truly individualist filmmaking and explore the language of cinema beyond the prescribed forms and national framework. The Chinese film industry is going through great transitions, the future is even harder to predict than the changing moods of film censors. The only thing left for us to do is to wait and observe.

The True Colors of Latin American Tricksters

By Rodrigo Garay

On Raúl Ruiz & Valeria Sarmiento’s The Tango of the Widower and its Distorting Mirror (El tango del viudo y su espejo deformante, 2020) and Matías Piñeiro’s Isabella (2020).

Old meets new in the 2020 Berlinale line-up. Forum, the most radical section of the festival, turns 50 this year and somehow embodies the duality of avant-garde and long-standing tradition in the latest Raúl Ruiz/Valeria Sarmiento post-mortem collaboration: a film that represents both the past and the present. Sarmiento took Ruiz’s unfinished rolls from the 70s and turned them into a whole new monster. On the other hand, Carlo Chatrian’s administration launched Encounters: a fresh selection of plural aesthetic perspectives that includes Matías Piñeiro’s latest ‘shakespeareada’—a modern take on a lesser-known comedy of the Bard.

Both features deal with ambivalent characters that could be partially deciphered with the help of two particular pieces of literature. A Pablo Neruda poem and a William Shakespeare play each hold the key to unlocking these deceivingly alluring tricksters’ true colors.

Raúl Ruiz shot The Tango of the Widower and its Distorting Mirror right before Augusto Pinochet’s coup d’état in 1973 threw him into exile and, hence, was never able to finish it. If he had, it would’ve been his first feature film. Now, almost fifty years later, his former wife and editor Valeria Sarmiento has reassembled the pieces of celluloid that he left behind into a wicked and beautifully psychotic palindrome of a crime flick.

First we see, lying on the bathroom floor, a woman whose death makes protagonist Clemente Iriarte’s status as a widower effective immediately. Poor, poor man. He walks alone in the black-and-white streets of Santiago de Chile, he meets with friends looking sorry, like a ghost, and for a brief second, he inhabits the world of an early Éric Rohmer moral tale—perhaps a little bit drunker, and a little bit crazier. Clemente can barely sleep at night; tokens of his wife haunt him in dreams, and this gradually becomes a living nightmare.

There’s a sense of the old French poetic realism in the dark euphoria that unveils Clemente’s fall into madness. Think of The Tango of the Widower and its Distorting Mirror’s camera as a fly trapped in a poorly ventilated room. A lively creature inside a tiny prison cell, it buzzes around with no sense of direction other than the one established naturally by its own mortality. It’s not performance, storytelling, nor the visual effect that dictate where the shot is directed or how it is framed, it’s the fact that its time is finite. Instinct as a way to film one man’s destiny.

By the magic of Sarmiento’s editing, The Tango of the Widower and its Distorting Mirror starts moving backward halfway through its runtime. It literally rewinds. Conversations make no sense any more, people walk facing the other way, doors open and close in the opposite direction. Events repeat themselves but twisted. Only when we get to the beginning of the film (which is now the ending) and watch it in reverse, we realize what truly happened to the wife lying on the bathroom floor. Neruda’s namesake poem “El tango del viudo” foreshadows this in its first few lines:

Later you’ll find, buried by the coconut palm,

the knife I hid there for fear you’d kill me,

and now, suddenly, I’d like to smell its kitchen steel

accustomed to the weight of your hand and the shine of your foot:

under the dampness of the earth, among the deaf roots,

of the human languages only that of the poor could know your name,

and the heavy earth doesn’t understand your name

made out of impenetrable, divine substances.[1]

So the man is a widower by his own making. Clemente, you bastard. This metaphorical knife was hidden all along in the normal sequence of events; once you read the scenes backward, it reveals itself. “Aquí no ha pasado nada,” says the voiceover, suddenly comprehensible: nothing happened here. Keep moving.

A more intricate time puzzle unfolds in Isabella, written and directed by Matías Piñeiro. Our main character, Mariel, is trying really hard to get a part in a production of William Shakespeare’s “Measure for Measure”. To prepare for the audition process, she’s helped by Luciana, an intriguing young actress who seems confident and successful. Luciana practices lines with her, gives some tips and clever exercises to improve her delivery. Her old friend is so knowledgeable of this particular role because it’s actually hers: since she gets an unmissable job opportunity in another country, Luciana is unable to do the Shakespeare gig and is training a proper replacement.

We’re left to patch this sequence of events on our own, with visual cues that range from the humane (pay close attention to Mariel’s pregnancy and early motherhood) to the purely abstract (a light installation takes up the screen and flashes pink and purple hues every now and then—eventually becoming part of the story), immersed in a labyrinth of non-linearity and time fractures.

The only constant in this game of past and future is a cloud of disappointment permeating the entire movie. Luck doesn’t seem to strike for Mariel. She fails to get the part and doesn’t really understand what’s expected of her when that happens. This is verbally emphasized by one of Piñeiro’s favorite rhetorical devices (one he shares with his friend and fellow filmmaker Nicolás Pereda): repetition. Through Isabella’s lines, a dialogue that soon becomes a frantic monologue, Mariel begs chance for mercy.

Isabella –

Too late? why, no; I, that do speak a word.

May call it back again. Well, believe this,

No ceremony that to great ones ‘longs,

Not the king’s crown, nor the deputed sword,

The marshal’s truncheon, nor the judge’s robe,

Become them with one half so good a grace

As mercy does.

If he had been as you and you as he,

You would have slipt like him; but he, like you,

Would not have been so stern.

The third line from the bottom perfectly captures the dynamic between the two leads. If she had been like you and you like she: Mariel by Luciana, Luciana by Mariel. From the latter’s point of view, their relationship is one of cosmic unfairness. Why is the other so talented and natural? How is she doing it? In apparently random order of alternating plot points and non-sequitur encounters, there is a series of almost identical panning shots spread throughout the movie that follows Luciana on her way to the same audition she’s insisting Mariel go to, the camera hiding behind a corner. Isabella’s camera is a sick voyeur trying to unravel something secret from a distance.

We soon learn that Luciana stole back the part. Was this easy-going and charming ally prepping her new colleague just to take her desire away in a last-minute act of treachery? So little is known about her that we’re left wondering. In Shakespeare’s dialogue, Isabella pleads to an abusive power figure that wants to take advantage of her sexual innocence. A vampiric despot craving flesh. Mariel inhabits her role intertextually when she says the proper words, making Luciana, in a way, a veiled and sophisticated tyrant. Like Clemente’s criminal intentions in the Neruda poem, her whole conundrum is encapsulated in Isabella’s plea. Poetry and violence keep finding their way in Latin American cinematic artistry, it seems. Images and words, literature and cinema, clashing together, vibing in unison. Perhaps it’s just me, but Borges, Carpentier, Arenas, or Pessoa keep coming back to meet an audience every time Piñeiro, Llinás, Ruiz, or Guzmán make their characters speak for too long.

Transcending the Race Barrier

By Sadia Khalid

From First Cow (2020) to Berlin Alexanderplatz (2020), this year’s Berlinale offered hope for greater racial harmony and inclusivity.

Every February, May, and September, the film fraternity makes pilgrimages to Europe to attend the three almighty film festivals in Berlin, Cannes, and Venice. These festivals, some of the highest authorities in determining the future of films, have long been accused of being Eurocentric. Although there may be ample evidence to that, the wind seems to be shifting favorably towards diversity, at least for the time being. Many films at the Berlinale this year were adequately multicultural, enough to offer hope for greater racial harmony and inclusivity, even if it’s only within the realm of cinema.

Bi-racial duos dominated the storylines of several films at the Berlinale this year. In the Competition section, First Cow and Berlin Alexanderplatz trailed two such leads fused by their collective struggle to survive in a savage world. Berlinale Special entrant High Ground (2020) saw a white bounty hunter team up with an indigenous tracker to settle an old score, while I Dream of Singapore (2019) from the Panorama Dokumente section featured a local NGO manager’s ardent attempt to relocate a migrant Bangladeshi worker. What do these pairs have in common? A shared goal and a sense of humanity over racial identity.

In Kelly Reichardt’s First Cow, an unlikely friendship brews between a taciturn cook, Figowitz, nicknamed “Cookie,” and a lone Chinese fur trapper, King Lu, in 1920s Oregon. A stranger among his own kind, tormented by his employers for his pacific nature, Cookie finds a reliable companion in Lu. The film doesn’t endorse any of the racial stereotypes that have plagued the Western genre for decades. The Chinese protagonist is more pragmatic than superstitious, unlike in most other films where the global north and south intersect. In the beginning, Cookie mistakes Lu for a Native American exposing his lack of familiarity with his comrade’s heritage. However, that doesn’t impede him from wholeheartedly trusting this mysterious man from a faraway land. Eventually, the real “secret Chinese ingredient” in the irresistible oily cakes the duo sells to make a living turns out to be a solid friendship.

A harsh contrast to Reichardt’s predominant visuals of earthy green forests is the neon-lit concrete jungle of Burhan Qurbani’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, which touched on issues of illegal immigration with the lead Franz, who escapes from West Africa and lands in Berlin only to get entangled in further tribulations. An immigrant himself, Qurbani examines how stateless persons can be dragged down dark paths. This poetic adaptation of Alfred Döblin’s 1929 classic novel injects here and there existential explorations of what it means to migrate. In an intimate moment with Eva, a club owner of Nigerian descent, Francis reflects, “There is so little sun in Germany, if I stay here long enough, I will become White.” Lying by his side, still panting from exhaustion after intercourse, Eva confesses she sees the world through “white man’s eyes” after spending many years in Germany. In another scene, Franz howls at his associates to not call him a refugee, but an immigrant instead. The distinction was somehow important to him to preserve what little dignity he had left. At home, race never came up once in his passionate love affair with German sex worker Mieze. One of the racial slurs we hear is kingpin Pums repeatedly calling Franz a gorilla. But even Pums soon sees himself in Franz, seduced by the same man to a lamentable point of no return. The gorilla metaphor comes back later in another form, from another person: psychotic wheeler-dealer Reinhold, who hands Franz a gorilla costume for a party. While Eva points out it was meant as an insult, Franz takes it sportingly, confident his “friend” wasn’t a racist. Their misfortunes, in the end, are derived from their statelessness rather than their race.

If Qurbani’s Berlin signified a microcosm of post-colonialism, then Stephen Maxwell Johnson’s High Ground embodied the horrors of colonialism. The vast wastelands of Australia provide a beautiful backdrop to an inhuman tale of a massacre. Mirroring true events of an unintentional butchery of an indigenous tribe in 1919, the film revisits the misfortunes inflicted on the natives by European settlers. However, one of these immigrants, Travis (Simon Baker) has his heart in the right place right from the start. He takes massacre survivor Gutjuk under his wing, even going as far as to kill his own people who murdered the Aborigines. He differs from the white savior archetype, as his actions are not fueled by a desire to lead a disadvantaged race. His quest is personal, one of cleansing a guilty conscience. Despite Travis’ best efforts to “not make it easy” on the settlers to wipe the natives clean of their heritage, his allegiance is misconstrued. “You can’t share a country,” exclaims fellow policeman Eddy when the natives turn on Travis, as though to justify the ethnic cleansing he has been facilitating for over a decade. The film reimagines the Western genre yet again, differing from First Cow in both tone and visuals; sunny and somber as opposed to Reichardt’s damp and light-hearted take.

Among the documentaries that featured such a central pair was Lei Yuan Bin’s I Dream of Singapore, which illustrates the struggles of migrant unskilled workers. The shiny cityscapes of Singapore may look like a dream from afar to Bangladeshi village boy Feroz, but the life he can afford there with his low wages is less appealing than the poverty that surrounds his ancestral home he is so eager to escape. When he is injured on the job, and his employers discharge him without compensation, the director, with the help of an NGO, assists him to pay for his medical bills and relocate back to his country. The strong bond this pair forms in the process manifests in a long, heart-warming parting scene. This observational documentary consistently breaks the fourth wall, inviting the audience to join the crude expedition of this accidental bi-racial duo.

Through these and many more films this year, migration and immigration emerge as a timely theme. Racial tension, in many of these films, takes a back seat to compelling personal stories that ring true across continents. The human condition supersedes any socio-economic or political construct and visionary directors once again capture this phenomenon through characters of varied cultures and colors. Although I can’t vouch for the other two mighty festivals, with an array of diverse films, the 70th Berlinale certainly did due diligence to tackle the blame of Eurocentrism.

New Life Rising From the Deep

By Savina Petkova

Water myths haunt Undine (2020) and Red Moon Tide (Lúa vermella, 2020), doubling as vehicles to comment on the social fabric of the present day.

It is usually said that mythology is a structuring element of ancient societies, a way to interpret the codes of unknown worlds. Rather than taming the chaotic forces, myths can generate meaning in their interaction with reality. When cinema, as a modern-day myth-making machine, engages with folklore, it turns its structures inside out, erupting into the unknown. A sea creature takes a victim and stops time. A woman bound by her sea spirit curse has to kill the man that does not love her back. Such are the premises of Christian Petzold’s Undine from Berlinale Competition and Lois Patiño’s Red Moon Tide, which screened as part of the festival’s Forum strand.

In these two films, water myths clutch the cinematic world so firmly that it is forced to burst out and transform. This can be a symptom of the past weighing down on the present and an urge to break away from patterns. However, this oscillation between gravity and freedom also forms a wave-like motion that intertwines their inherently political messages – the relations between myth and present times. While both directors approach aquatic legends from their own culturally specific perspectives, they ultimately end up arriving at the same motif: life conquers myth. Also, dealing with time, the films propose a break from cycles and repetitions, which serves as an exit point of trauma and mourning, like cutting through a swollen wound.

Red Moon Tide composes its mythology out of a real story – the disappearance of a local fisherman named Rubio, which disrupts time and the social order in a small village on the Galician coast. A region with rich folklore from its Celtic origins through Roman times and the Caliphate, to its autonomous state as a Gaelic kingdom, it is no wonder that a cinematic rendering of Europe’s Western end has mythopoetic potential. The camera caresses the old wall of a dam, rusty waves stratifying the past through marks of water levels, now dried up, while the dam in Undine offers both salvation and a death threat for industrial divers. Aside from its multi-layered history and culture, it is the overbearing presence of the sea that has shaped most of the folklore narratives of northwest Spain.

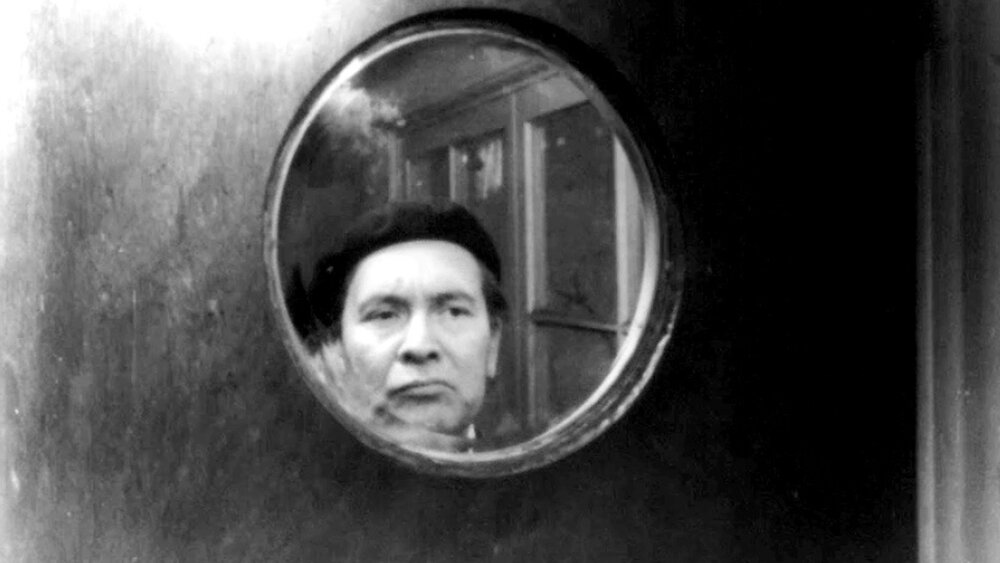

Lois Patiño’s first feature, Coast of Death (Costa da morte, 2013) pays attention to man and nature – shipwrecks and fishermen are seen as equals in a contemplative documentary. Red Moon Tide takes a bolder look at the interactions between land and water as its narrative slowly deteriorates, mirroring the entropy of time in the film itself. Rubio, the diver that retrieved dead bodies from the sea to return them to their loved ones, is reduced to a whisper in the film’s underwater opening sequence, with the graininess of a million little air bubbles piercing the screen. Looking up from the bottom of the ocean, the camera assumes the point of view of a drowned man or sea creature, while a voiceover speaks of a monster’s predatory instincts.

Undine, on the other hand, never openly manifests its story’s origins and transforms the myth by putting forward a real story – a love story. Instead, it proposes a first name – Undine Wibeau (Paula Beer). In a way, it is the viewer who is asked to be already acquainted with the sea spirit folklore, particularly with the name (Latin for ‘wave’), given by German Renaissance thinker Paracelsus. However, elemental spirits and especially aquatic ones are usually associated with femininity and desire, while also questioning the possibility of love, up to Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid”. Christian Petzold was inspired by Ingeborg Bachmann’s novel “Undine Leaves”, which problematizes female agency when subjected to a curse such as this – having to kill the man you love if he one day leaves you. Petzold’s film is more about becoming human as a result of a rupture of the heroine’s own patterns of life as a sea spirit, yet she is presented mostly as Ms.Wibeau, a historicist of urban development, which also puts her in a decisive position in relation to the past.

Both films interrogate the need to revisit the past and by returning, one can reinvent, rather than invent, a future. In its long, meditative takes, stasis overpowers all the villagers in Red Moon Tide. Absence echoes from the dislocation between images and sound, as voiceover narrates what seems like monologues over the visuals of unmoving bodies. Warped in a never-ending present, the protagonists of the film utter Rubio’s name, describe his mother’s grief, and build in the legend of the monster which rises with the moon, “washing their blood away.”

Lois Patiño shot the film himself and did so as a still life, with interior compositions that trap their objects in a fixed time and place, held firmly by the camera’s gaze for minutes at a time. Animals pass through the frame unaffected by the paralytic curse but even their motions don’t seem to make the camera tremble. Attentive to solid structures, Patiño films coastal rocks in a way that unearths their hypnotic potential. In long, repetitive sequences, the camera lingers on their shapes, as their otherwise smooth surfaces crease into one another and form fissures into which one can disappear. An oneiric film about the silence of infinite time, Red Moon Tide thirsts for salvation by water.

Undine also saves its protagonists with the help of water. A massive aquarium bursts into pieces over two strangers that have just met, shedding glass all over a restaurant floor. Carpet drenched, clothes soaked, tiny rivers trickling down the wooden support that now stands bare as bones. Water engulfs a fated meeting at the beginning of the film, following a merciless break-up opening. Moments after Undine has realized her lover has left her for another woman and she is obliged to kill him, she stumbles upon Christoph (Franz Rogowski), a kind and warm man who looks at her with curiosity and burgeoning adoration. Then the tranquil world, both the actual one and the one held in the aquarium, explodes. Coming back to the mythology of undine spirits, this meeting is both fate and chance for the protagonist since the presence of Christoph poses an opportunity to break away from her own curse and the bond of her violent nature, surrendering herself fully to love.

From that moment on, Undine frames the relationship that blossoms as a singular experience, leaving behind all repetitions, flashbacks, sequence replays, and memories that the film resorts to when explaining how it feels for one to be without the other. It’s a recurring theme of Petzold’s films to have his characters miss each other, almost relegating them to different but parallel worlds. But in Undine, he supplies the audience with an example of a certain rarity. Christoph is an industrial diver who takes his time to muse over nature’s underwater wonders, such as a gigantic catfish or an engraved ruined bridge while being a good worker who does a commendable job. In his face, Undine recognizes real-life thrusting into her old nature, as if Christoph has plunged himself into her (him being the diver, her being, essentially, water).

By approaching marine mythology from reality (Undine) and to reality (Red Moon Tide), both films comment on the social fabric of the present day. The push and pull between fantastic elements and realism is also used as a thrust for transformation, the need for which is shared by the two directors. While Red Moon Tide makes the viewer thirst for its missing waves by singling out details such as salt scattered on a dusty table, Undine drowns its audience in both water and love, appealing to the emotional tides that mark a break in an otherwise repetitive narrative. Stepping back before one can leap forward – such a bodily motion is also made up of a hidden wave of movement that spans head to toe. Since water is regarded as a female element, unsurprisingly movement, future, and change intertwine in this desire to quench the spectator’s thirst.

[1] Translated from the original Spanish by Lewis Hyde:

Enterrado junto al cocotero hallarás más tarde

el cuchillo que escondí allí por temor de que me mataras,

y ahora repentinamente quisiera oler su acero de cocina

acostumbrado al peso de tu mano y al brillo de tu pie:

bajo la humedad de la tierra, entre las sordas raíces,

de los lenguajes humanos el pobre sólo sabría tu nombre,

y la espesa tierra no comprende tu nombre hecho de impenetrables substancias divinas.