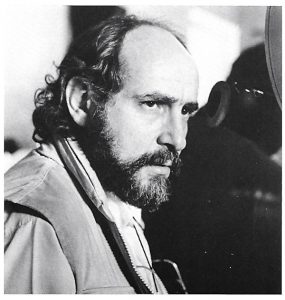

FIPRESCI Platinum Award 94 to Arturo Ripstein

Arturo Ripstein

The Poet of the Dark Side of the Mexican Bourgeoisie

Klaus Eder on Arturo Ripstein

His father produced films. One of his friends was Luis Buñuel, the great Spanish director. Buñuel had left Europe in 1946 and had found a new home in Mexico (where he made great movies). Buñuel was a regular visitor to Ripstein’s house, and the young Arturo was a regular visitor to the film studio where Buñuel worked. Nazarín impressed him, for El ángel exterminador (The Exterminating Angel) he could work somehow as Buñuel’s (non-credited) assistant. Buñuel’s magic (and his professionalism) had an influence on him, see El castillo de la pureza (The Castle of Purity, like Buñuel’s Angel exterminador a film about people who cannot leave a room, the film is considered as a classic of Mexican cinema. “In my films the family is a catalyst for destruction” said Arturo Ripstein).

In those days, middle of the sixties, Arturo Ripstein (born 1943) made another friendship, with a young, not yet much known writer, Gabriel García Marquez. The Colombian author offered him a script he had written earlier (following one of his novels). Another author, Carlos Fuentes, wrote the (Mexican) dialogues. Tiempo de morir (Time to Die) became an attention-getting first film. The critic Tomás Pérez Turrent wrote: “It is one of the most successful and promising debuts in Mexican film history.”

Tiempo de morir marked a turning away from the popular Mexican entertainment cinema and from the Hollywood images of Mexico (folklore and adventure, Emiliano Zapata and Francisco (‘Pancho’) Villa, the leaders of the 1911 revolution, had become Hollywood heroes). Tiempo de morir marked the beginning of a new Mexican cinema. As in other Latin American countries (in particular Brazil), in Mexico a new, young generation of filmmakers appeared at the end of the ’60s / beginning of the ’70s, with films receptive to the reality of the country, films with a political, historical, social interest and engagement – made by directors such as Paul Leduc, Alberto Isaac, Felipe Cazals, Jaime Humberto Hermosillo. Arturo Ripstein is the only figure of this New Mexican Cinema who has been able to work continuously — to some extent — within the film industry, even if he is more tolerated than supported by it. His oeuvre mirrors the development of Mexican cinema from 1965 to today.

His career continued from the 60s successfully into the 90s and 2000s and until today, with entries in the Cannes and Venice competitions, with retrospectives at a diversity of festivals, and with calls into juries. However, his unmistakable filmic universe had already been shaped in his early work, and he varied, fine-tuned and daringly extended it permanently. A film by Arturo Ripstein can distinctively be recognized as a film by Arturo Ripstein. Even if he worked always within the existing structures of the Mexican film industry, he (almost) always managed to make the films he wanted to make: a real author.

Arturo Ripstein’s universe is painfully and hermetically closed; there’s no way out. It’s a dark world without exit. It’s also a universe which, in its surreal aspects, is influenced by writers (Carlos Fuentes, Gabriel García Marquez, Juan Rulfo, José Donoso, also Manuel Puig and, surprisingly, Naguib Mahfouz). Ripstein manages to build, with power and without pity (and preferably using long shots and an artificially moving camera), invisible walls around his characters, as if they lived in a prison – a prison made up by the Mexican society and its social and moral conventions and its strong Catholicism (which he sometimes contests with a cynical anti-clericalism). In El castillo de la pureza these walls are even tangible: a family is not allowed to leave its house. In Ripstein’s grief-stricken micro cosmos, ‘society’ is fully present – as in La reina de la noche, where the story of a bohemian folk singer in the 40s is populated with immigrants from Spain and Germany. That’s why Ripstein is not at all an apolitical filmmaker – just the opposite. He finds and analyses politics in the kitchen of ordinary people – meaning us all; some of his films are melodramatic studies of an ordinary fascism, others show the vulnerability of human beings. It’s difficult to elude this dark world which penetrates its characters merciless until it finds the hidden corners of their souls – like Dionisio Pinzón in El imperio de la fortuna, whose rise and fall touches all the ups and downs of human existence.

Arturo Ripstein is the poet of the dark side of the Mexican bourgeoisie. He tells Mexican stories which involve us all, and he tells them in a highly personal and, at the same time, very Mexican style. After having seen his films you’ll see Mexico with other eyes.

Ripstein: “The first duty we have as filmmakers in Mexico is to look at our reality and see what’s happening. We must look in our own backyard. At our own history. The only way to be universal is to be ourselves.” To realize this, he can count on one of the best scriptwriters on the continent, Paz Alicia Garciadiego, who writes and co-writes his films since El imperio de la fortuna (the adaption of Juan Rulfo’s El gallo de oro, 1986, with Ernesto Gómez Cruz as a handicapped loser trying his luck with cock fights).

Arturo Ripstein’s films talk about the art of survival. The necessity – or senselessness – of survival. The pain of survival. Profundo Carmesi (Deep Crimson, one of his most known films, awarded in Venice 1996) is a dark, pessimist, sharply ironic view on man and a woman who base their love on blackmail, on violence, even on murder. A not less dark image of life unfolds Así es la vida (Such is Life). It’s the story of Medea, transferred to nowadays Mexico. A woman has been left by her husband; all attempts fail to win him back. At the end she will take a terrible revenge, by killing her own children. Así es la vida is one of the first films where Arturo Ripstein used a small, mobile camera which allowed him to register the narrow social world of the heroine (the wonderful Arcelia Ramirez) in a precise way. Another great actress can be adored in La perdición de los hombres (The Ruination of Men), Patricia Reyes Spíndola. The title of the film refers to an old Mexican song about machos complaining their fate. Two women fight over the corpse of a ladykiller. As most of his films, La perdición de los hombres is also a film about filmmaking, using the language of cinema (the new digital technics) in a daring and even experimental and curious way. From this point of view, Arturo Ripstein’s films are more modern and audacious (see his use of the camera and his unexpectedly long shots) than a lot of nowadays movies.

What does Mexico mean for you? Ripstein: “That is a difficult question. A few places. A few people walking along a street at night. The volcanos. The pollution which is slowly the death of me. My house, my wife. My eyes. Mexico is a dead landscape. lt is Hell.”

Klaus Eder

(The quotations are extracts from a conversation Klaus Eder had 1989 with the director in Mexico City for a publication on Arturo Ripstein.)