The festival was held in digital format and the jury was only given access to the films in the FIPRESCI competition. Since it is not possible to write about a festival that we did, in fact, not attend, I offer here instead a brief overview of the films we did see.

Sweat (2020)

Director: Magnus von Horn, Poland/Sweden

A thick layer of loneliness lies over this Polish film about a young fitness guru and influencer. She has 600,000 followers on social media, but no one is close enough to hold her hand and tell her she is loved.

Sylwia is a child of her time, as is the film, and Magdalena Kolesnik makes a great impression in a demanding lead role. Michael Dymek uses the camera to both closely investigate Sylwia’s face and at a distance reflect modernity through house façades, glass, mirrors and surfaces that both bear an architectural distinctiveness and a beauty, but also shine with a cold emptiness.

The film is worth seeing, but tells nothing new about stardom, narcissism and loneliness.

This is not a Burial, it’s a Resurrection (2019)

Director: Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese, Lesotho, Italy, South Africa

This film is both universal and specific South African, and it is as unforgettable as the late Mary Twala (and her face) in the leading role as Mantoa, an old lady reaching an emotional ground zero when her son dies. He was the only one she had left.

But when the village is threatened by a dam construction that will overflow the landscape, and the ancient graveyard, Mantoa rises with grief and anger.

There is an almost documentary depth in the way the film shows how “progress” hits the villagers like a steamroller. At the same time, Pierre de Villier’s stunning camerawork, together with the excellent sound, gives us a rare and impressive audio-visual experience.

And Tomorrow the Entire World (Und morgen die ganze Welt, 2020)

Director: Julia von Heinz, Germany/France

The film’s energy is as high as its timeliness. It focuses on some of the questions that have occurred in both Europe and the USA in recent years: How to demonstrate against racists and neo-Nazis?

A law student, Luisa (Mala Emde) joins a collective of Antifas who live, demonstrate and party together. Among the young idealists, the meanings and motivations differ. Some want to just have fun, throwing cakes in the face of the neo-Nazis. Others tend towards more physical confrontations.

Von Heinz points at some structures in German society that indicate certain links between the police and the neo-Nazis, and how these links threaten the constitutional rights of young people.

Using the character Dietmar (Andreas Lust), a former revolutionary who has been in jail for illegal activities, the film also points back at Germany’s past, such as the Rote Armee Fraktion (Red Army Faction)/Baader-Meinhof group, but leaves it for the viewer to draw conclusions.

The sometimes almost frenetic camerawork catches the pulse and energy of the young people and their actions. The film would have been more focused without the erotic tension between Luisa and two of the guys in the collective. But this also gives quite a precise description of a young community where revolution, sex and partying meet in an often explosive mixture and on several levels.

Father (Otac, 2020)

Director: Srdan Golubovic, Serbia, France, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Slovenia, Croatia, Germany

The curse of poverty could have been the title of this quiet drama. The father, Nikola, appears as an almost biblical character, like Job in the way he is confronted with impossible trials, like Christ in his stoic way of meeting them.

The theme also turns the director into a kind of Serbian Ken Loach: When a tragedy linked to the family’s poverty occurs, Nikola is ordered to give up his two children to social services. He will get them back if he gets a stable job. But there are no stable jobs in the village. This Gordian knot is also tightened with corruption, which Nikola tries to release by appealing to the Minister of Social Services in Belgrade. But moneyless as he is, he has to walk the 300 kilometres to deliver the appeal by hand.

This changes the film into a road movie, where Nikola is like a pilgrim for justice. Slowly the film takes us closer and closer to the man, even though the dialogue is sparse. And the film also takes us through a rural, decayed and poor Serbia, in contrast to the modern city where he arrives.

A strong, outrageous and watchable film that maybe does not tell us anything new about the theme, but points a poignant finger at the conditions in modern Serbia. It is beautifully shot and with impressive acting, especially by Bosnian Goran Bogdan in the lead role.

Ecstasy (Êxtase, 2020)

Director: Moara Passoni, Brazil

To me, this essayistic, impressionistic documentary was an immersive experience. The director uses both her own and other people’s experience with the eating disorder anorexia to build up an almost abstract narrative where a fictional character, Clara, tells her story by voice-over. That allows her to jump back and forth in time, from the moment when she was a foetus in her mother’s womb during one of the many riots during the junta era in Brazil, to her grown-up age. Clara’s voice takes us right into the core of the illness: the mindset and strategies of the ill, and the paradoxes of the illness. Passoni draw lines from architecture, religion and politics, to the ballerina’s need for both flexing and control.

The film thematizes anorexia in a way that both binds the illness to the body specifically, to skin and bones and fat, but at the same time lifts it out of the individual suffering and into a bigger picture.

Together with Janice d’Avita’s fluent camera and the often almost transparent pictures, and sound designer Cévile Chagnaud’s exceptional work, this forms a multi-layered film rich in texture, thoughts, pictures and ideas.

Scarecrow (Pugalo, 2020)

Director: Dmitrii Davydov, Russia (Yakutia)

This fascinating film takes place in a small community of Sakha, living in the northern part of Russia. Most of all, it is an extraordinary portrait of a woman. It is a tragedy, but it is partly told with a light-hearted take on her situation.

Valentina Romanova-Chyskyyray, a folk singer, gives a remarkable interpretation of the unnamed woman, a healer and a drunkard living in an awful place. She is bullied by the people in the village, but called upon when someone is sick, a husband is impotent or a child is stuttering. The healing costs her a lot. But she also has a heavier cross to carry than her need for vodka.

The landscape is bitterly cold. Winter and snow make the outdoor scenes almost black-and-white. Davydov combines an original story with traditional Russian cinematic art.

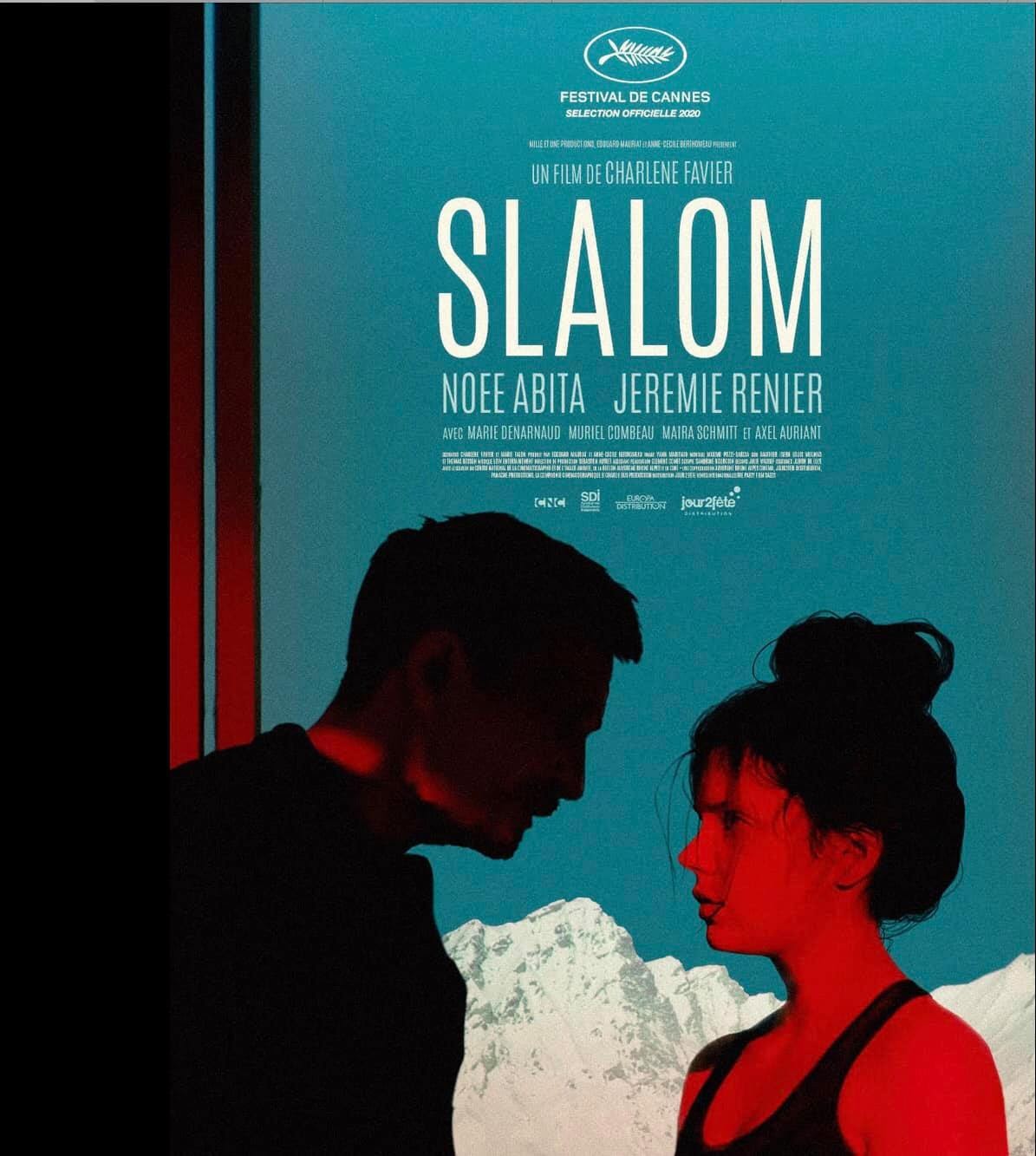

Slalom (2020)

Director: Charlène Favier, France

This is #metoo in the slalom environment, but it is also much more. Favier combines a coming-of-age story with a story of abuse, told with many nuances and a stunning cinematic power.

The young actress Noée Abita gives an impressive interpretation as Lyz, a 15-year-old talented slalom runner. She spends the winter in a training centre in the Alps, led by Fred (Jérémie Renier), who uses quite tough methods. Several issues in Lyz’s life makes her vulnerable.

The film uses the magnificent alpine landscape in a fascinating way, making the mountains on the horizon look both threatening and enticing, mirroring both the possible future career of Lyz, and Fred as character, man and coach.

Similarly fascinating is the use of colour, with extensive use of red, alternating with the white landscape. Danger and innocence. Warmth and cold.

Dealing with a provocative theme, the film is pleasantly “not angry”, although it has some really nasty (and therefore “good”) scenes and examples of sexual manipulation.

The Truffle Hunters (2020) by Michael Dweck, Gregory Kershaw – the winner of the FIPRESCI prize – will be reviewed separately.

Britt Sørensen

© FIPRESCI 2021

Edited by Birgit Beumers