The Quiet Spring of Love: Chronicles at IFFK

The 30th International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK) concluded on a jubilant and quietly assertive note, reaffirming its role as one of India’s most vital platforms for independent and world cinema. In an ecosystem increasingly shaped by algorithms, instant gratification, and spectacle-driven narratives, IFFK 2025 stood its ground as a space for reflective, humane, and politically conscious storytelling. As aptly observed by noted filmmaker Saeed Akhtar Mirza, who was honored at the festival’s closing ceremony to mark his 50 years in cinema, “No place in India that has such a tremendous history of cinema as Kerala. When this State honours me, it means a lot to me“.

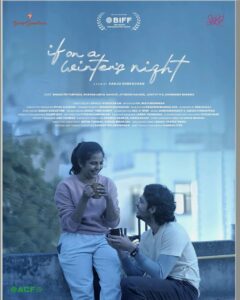

Among the festival’s assorted global offerings, two Malayalam-language films – If On a Winter’s Night (original title: Khidki Gaav) by Sanju Surendran and Desire (Moham) by Fazil Razak, emerged as some of the most discussed, and celebrated works among cinephiles.

Their recognition was not incidental. If On a winter’s Night received the FIPRESCI Award for Best Film in the International Competition, while Desire won Best Malayalam Film by a Debut Director. At a moment when Malayalam cinema is emerging as a renewed phase of new wave filmmaking within the Indian cinematic landscape, these two films add a decisive feather to its cap – not through novelty of subject alone, but through rigor of craft and emotional sincerity.

Spending nine eventful days at IFFK 2025 as part of the FIPRESCI jury inevitably prompted larger reflections. One question lingers insistently: what would become of independent cinema in the absence of film festivals? In an industry where theatrical spaces are shrinking and digital platforms privilege marketable familiarity over artistic risk, festivals remain among the last democratic sites where vulnerable, small, and uncompromising voices can be seen, discussed, and validated.

A second question follows closely. The films that won or deeply resonated this year were not “absolute stunners” in the conventional sense. In a world where stories circulate endlessly at the touch of a screen, very little feels entirely new. What, then, moves us?? The answer lies not in the originality of the plot, but in the integrity of the vision. It is the craft, abstinence and sincerity of feeling that touch the audience- the human being behind the data profile, the so-called high-value customer of the digital universe.

Against a cinematic landscape dominated by superhero franchises and reverential biopics, If on a Winter’s Night and Desire stand out as quiet but towering beacons of radical empathy and technical grace. Both films probe the enduring and often brutal boundaries of social exclusion, examining the fragile antidotes required to heal a deeply toxic world.

At its core, If on a Winter’s Night taps into a narrative painfully familiar to Indian audiences: the migrant’s (?) search for belonging in an unfamiliar city. This is not merely a story of economic hardship but an unflinching examination of cultural, linguistic, and visual discrimination, of how cities police belonging through accent, appearance, and unspoken social codes. The original title Khidki Gaav is itself a provocation. It functions as a metaphor for a society that peers through metaphorical windows- intrusive, vigilant, and steeped in conservative prejudice- habitually breaching the private lives of others. In this sense, the film extends beyond personal struggle to comment on a culture of constant surveillance and moral policing. While the broad contours of Khidki Gaav echo earlier works such as The Namesake ( 2096) , Minari (2020) , Citylights ( 2014) and the art house classic Gaman ( 1978), the film’s power lies in its execution rather than its premise.

Sanju Surendran’s objective perspective is essential in this context. We sense what might be approaching in the narrative, yet the film resists melodrama. Instead, it anchors itself in production design and a tightly observed screenplay that compels the viewer to remain emotionally invested. Prejudice, societal pressure, and financial instability are not fore grounded as dramatic events but embedded into the everyday texture of life. In this regard, the film evokes the spirit of Basu Chatterjee and Basu Bhattacharya– Piya Ka Ghar (1972), Rajnigandha (1974), Anubhav (1971), Avishkaar (1974)- where intimacy, routine, and small gestures carried profound social meaning. Yet If On a Winter’s Night remains distinctly contemporary, capturing the ruthlessness of present-day relationships while preserving tenderness through minute details of daily life: gestures of care, cycles of conflict and forgiveness, and the quiet spring of love under pressure. In one of the film’s most affecting sequences, a worn-down Abhi finds himself beside a live musical performance, joins the band without premeditation, and lets the moment breathe. What follows is a brief but powerful pause- music becoming a balm that tunes itself to the complexities of modern love and emotional survival.

Desire, on the other hand, is structurally and tonally unpredictable. Where Khidki Gaav derives strength from restraint and familiarity, Moham thrives on uncertainty. The film unfolds like an emotional chase, refusing the viewer narrative comfort. We move with Amala- played with haunting understatement by Amrutha Krishna kumar- through fractured memories, PTSD, and longing. Her performance stands out in the Malayalam competition for its subdued physicality, water-brimmed eyes, and sustained vulnerability. Amala does not demand empathy; she earns it through silence and endurance.

Contrast is the defining grammar of both films. If On a Winter’s Night, Sara (Bhanu Priyamvada), a pragmatic professional, is paired with Abhi (Roshan Abdul Rahoof), an easy going and endearing artiste. In Desire, Amala’s fragile interiority collides with Shanu (Ishak Musafir), a volatile, vengeful presence. These contrasts generate situations that oscillate between tenderness and recklessness, intimacy and danger. Importantly, neither film reduces its characters to moral binaries. Instead, they inhabit flawed, contradictory human spaces.

The denial of anticipated narratives sets apart Desire. The viewer is compelled to surrender control, following Amala as she follows the motorbike through roads, memories, and the darkest recesses of desire. The trio- Amala, Shanu, and the bike – becomes a moving metaphor for compulsion, escape, and emotional inertia. The film’s power lies in this surrender, in asking the audience not to judge but to accompany. Though one can discern a subtle echo of Sridevi’s iconic performance in Sadma (Moondram Pirai, 1983) within the emotional architecture of Desire. In Sadma, Sridevi’s childlike attachment to the puppy, Hari Prasad – an image that came to symbolize the film’s romanticized portrayal of amnesia- served as a fragile emotional refuge. Similarly, Amala’s fixation on riding the motorbike in Desire functions as a psychological anchor. In both films, desire is not indulgent but therapeutic, operating as a coping mechanism that offers fleeting relief from intense anxiety and emotional rupture.

Together, these films underscore why festivals like IFFK matter. IFFK strengthened my belief in cinema and the passion I carry for. The films selected remind us that cinema’s relevance today lies not in scale but in sensitivity. Films like If On a Winter’s Night and Desire do not shout for attention ; they whisper, linger, and stay. In doing so, they reaffirm cinema’s oldest promise: to make us see ourselves, and each other, with greater clarity and compassion.

Aparajita Pujari

©FIPRESCI 2025