A Portrait Of Age And Simple Lives That Is Both Luminous And Heart-Breaking.

Egyptian director Ahmad Abdalla has placed Middle East on the world map, leading a new wave of independent cinema in the Arab World.

Presented in the International Competition at the Cairo Film Festival, in world premiere, his latest 19B (also written by him) is a modern tale of solitude and isolation.

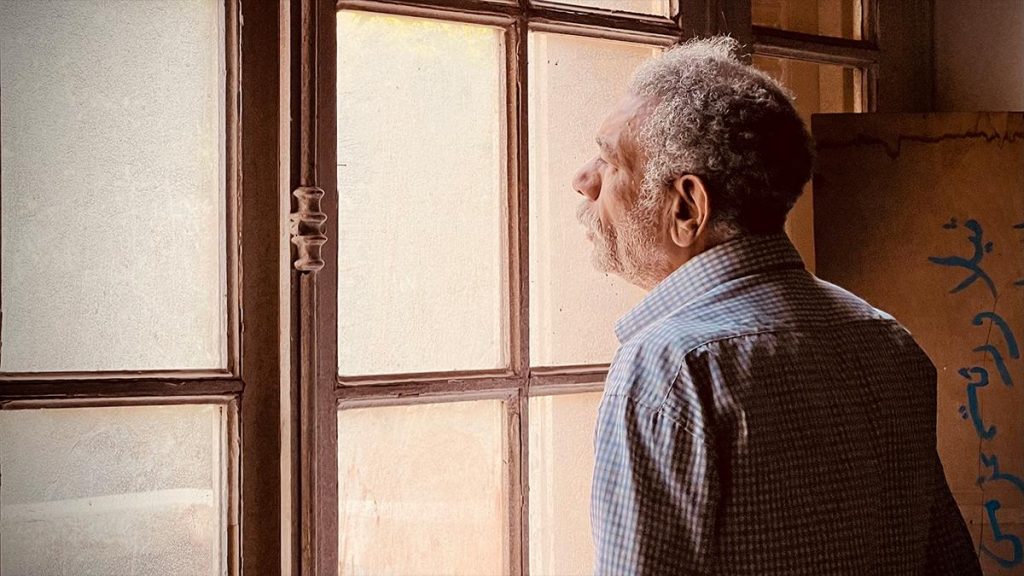

Our protagonist is an old man, Antar, who lives a reclusive life in an old villa where he has been the caretaker since the 1960s. He never hears from the owner of the villa, but his salary drops into his account every month and every day his routine is the same: opening the windows while in his pyjamas, feeding his cats and dog; he syphons electricity from next-door neighbour Sokkar, occasionally receives visit of his married daughter, Yara, and from the local doctor who loves animals and wants to rehouse a kitten. A collapsing wall gets ignored by the local authority. The old man and the old house, have something in common, age at first, a certain pride and an aristocratic aspect. The walls of the house—a large stone house off a side street, have something from the past, like Antar’s face, so sharply lit by the cinematography.

Antar’s trouble starts when Nasr, a petty criminal recently released from prison, arrives at the villa and identifies it as the solution to his needs. Rejecting his new housemate, Antar ends up sleeping on a bench of the garden of the villa. But what else can he do? Can he call the police? He is not the owner, but only the caretaker. Then a council inspector turns up to investigate a ‘complaint’ that Antar has bitten a child, an obvious lie, but it makes Antar think that there is not much left to do.

Ahmad Abdalla’s film has a remarkably simple story to tell, but the director seeks to render that story intensely poignant, full of poetry and compassion and showing a profound understanding of the human psyche.

Here he paints a sobering picture of the margins of society. A quiet narrative, underpinned with authenticity. In 19 B life is a simple matter and its mechanism is captured in its essence. Everything starts in a seemingly banal and unpretentious manner: an angry dispute with a man who insists on parking in front of the gate, the proverbial storm in a tea-cup.

This is a movie about invisible people that become visible to us, they are people trapped by their position in the world, lonely people, trying to endure their loneliness. But the sadness here is not inevitable; it is a consequence of a social structure, a political pathos. Antar and Nasar, the central figures of 19B embody a general defeat, and yet remain unique. Thus, it is a great urban film—set in Cairo, but that could take place in any big city of the world—leading us within the unseen (to middle-class eyes) city of the poor. The film permits us to penetrate both this teeming metropolitan world and enter the individual life, drawing us in with an attentiveness to sorrows which we might otherwise fail to consider. The film lays a claim on us with the unemphatic assertion that we ought to bear witness to such existence and tragedies. Here human beings are unguarded, naive, and possessed by a simple faith in life. The film never forgets how hard life is, and how in the end the only escape for the underprivileged is to leave the confines of the Earth altogether, like Antar and his neighbour, happily drinking tea at the end. But this is also a movie with a subtle message, full of love: what is left at the end of life is not what we have but how we have lived. Just as Antar does not own the property but is it’s a proud caretaker. In a society where modern buildings are eating old buildings, Antar’s strength is standing still, making him a modern hero.

This is a movie that takes one back to the glory days of art-house neorealism film in the 1960s and 70s, when you left the cinema not in need of food or drink, but a sympathetic person with whom discuss the film.

Rita Di Santo

© FIPRESCI 2022