Glimmers of Magic in the Dark: African Cinema from the Tiger Competition

The twelve films that competed in the Tiger Competition at the 55th International Film Festival Rotterdam, which I was able to watch and analyze as a member of the FIPRESCI jury, could not be more different from each other. They represent a diverse pool of national realities and cater to different sensibilities, tastes, and anxieties. Thus, the three African films in competition offer narratives focused on distinctive social, generational, and ideological groups, with one of them addressing a real historical issue. Nonetheless, aside from depicting comparable contexts of economic challenges, these films summon fantastic, surreal, and even supernatural elements that not only enrich their already intriguing narratives but also provide cultural subtexts that acknowledge the legacy of magic from their African ancestors. Considering my personal lack of exposure to contemporary African cinemas, I rejoiced at the opportunity to highlight and discuss these three notable titles.

Ique Langa’s O profeta (2026) is the film that explicitly brings this legacy to the foreground with its depiction of an actual witch who grants the faith-afflicted Pastor Hélder (Admiro De Laura) the power he needs to cure and lead his religious community, at the cost of binding him to her own power through a pagan ritual involving a snake. In doing so, Langa does not merely acknowledge the endurance and prevalence of black magic in Mozambican society. He also insinuates that this is a more compelling source of metaphysical power for the locals like the protagonist as opposed to the country’s colonially inherited Christianity. Pastor Hélder evidently hesitates before taking this last resort, and Admiro De Laura’s convincing rendition of sweat-inducing anxiety throughout the film suggests that this man is not moved by avarice but by fear. Still, he embodies religious and even political authorities who are willing to privately benefit from the immoral ways that they preach against in public. The film’s black-and-white format visually reinforces the battle between faith and magic, and this is especially perceptible in the sequences depicting the magic ritual and the pastor’s nightmares, filled with dramatic shots evoking life and death.

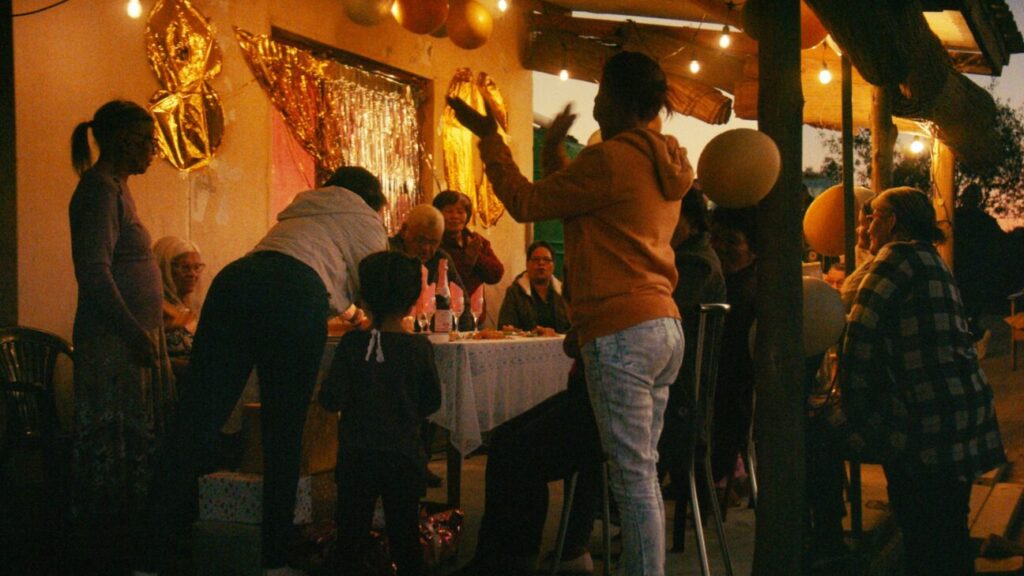

At the other end of the ideological and cinematic spectrum lies Hugo Salvaterra’s My Semba (Meu Semba, 2026), a youthful Angolan film filled with freestyle rap and vivid color that embraces and promotes Christian virtues in the face of economic inequality, abuse of power, and rampant criminality in Luanda. Spearheaded by soulful albino teenager X (Euclides Teixeira) and his “siblings” from an orphanage run by Padre Jonas (Clemente Chimuco), the film explores different kinds of problems affecting the local working class—70% of the population, as the protagonist reminds us in his verses. While grounded in social realism, the narrative’s tone is lifted by the lyrical energy from the numerous freestyle performances, especially those from X which also reflect the humility, kindness, and solidarity he learned from Father Jonas. It is a different kind of magic that enables the protagonist and his peers to survive in the concrete jungle and, against all odds, participate in a televised talent contest. Beneath the film’s Christian contemporary gospel lies a tradition of African ancestry evidenced by the Kimbundu term semba, an Angolan music genre centered on communal storytelling. In this way, Salvaterra’s feature vindicates the inherent resilience and optimism of Angolan youth.

The third film, Variations on a Theme (Jason Jacobs and Devon Delmar, 2026), stands out as a documentary focused on real governmental neglect: the unpaid services of South African soldiers during World War II. Elder goat herder Hettie is one of many descendants who sign up for a program that promises overdue reparations in exchange for a bureaucratic fee. The filmmakers closely follow her daily routine and those of her peers in rural Kambiesberg as they wait to be compensated. We therefore learn about the unspoken and unresolved traumas of their military ancestors, their own precarious livelihoods, and their plans and dreams for a seemingly richer future after they get paid.

The element of magic here lies less on the subjects and more on the film’s stylistic approach, which includes poetic compositions from mundane settings like the one of a man digging for diamonds on the floor of his own kitchen. There are also stunning transitions such as the opening and closing sequences revolving around a window in Hettie’s cottage. A more explicit rendition of magic are the swift moments of paranormal activity like moving chairs and glasses that are meant to signal the presence of Hettie’s deceased father. Bearing in mind that co-director Jason Jacobs is Hettie’s grandchild, this film also represents an intimate family portrait with wider social resonance.

All three films reflect the potential of African filmmakers to produce poignant characters, authentic narratives, distinct stylistic approaches, and luminous images despite limited budgets and other industrial constraints in their home countries. Their cinematic magic should be an inspiration to filmmakers everywhere, especially those coming from equally challenging backgrounds across the Global South. Thus, one can only hope that these titles get to be distributed and released far and wide, and to be properly experienced in cinemas. The International Film Festival Rotterdam surely serves as an exceptional launchpad for them, but the global film industry needs to figure out how these films can reach people elsewhere. My privilege as a jury member should be to watch them first but not to be one of the few in the world to watch them at all.

Gustavo Herrera Taboada

© FIPRESCI 2026