Notes on Havana: Some Shapes of the Stars

There’s something beautiful about that

That strange

That of

Programming and writing about films

A globalizing, neoliberal project, stalks hearts

And then

Pam!

A world that wants us isolated

And governments that individualize and nullify empathy.

And then we sit down

Sit down

So full body

Sit down

To look for the points in common

The things that some images share with others

And then

Pam!

A naive idea

A childish intuition

We (film critics and programmers) never work alone

The smallest unit of life is not a particle (or film), but the relationship between two

Sometimes films remind me the tenderness of the encounter and the possible imaginary communities of light

Movies remind me of many things

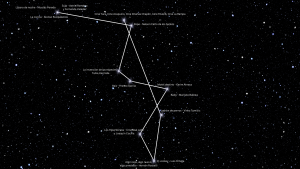

and suddenly, I’m sitting here, like a spectator of the sky

watching dots of light pierce the deep darkness of a movie screen

I sit down and wonder what the films can tell us about this thing that worries me so much, and I insist on calling it, a community? It is assumed that this text will work as a coverage of the 45th edition of the Havana International Latin American Film Festival. When I think of movie screenings, I almost always remember turning my head while the film was playing to see everything happening around me.

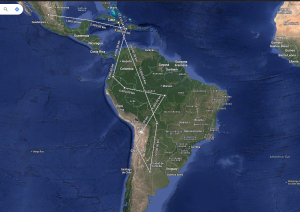

This was my navigation chart to write this text:

The points of light (i.e. the constellation that more or less indicated where I was walking) had the following shape:

There were 12 films spread out on a map of Latin American cinema. I approached, with care, the shape of this constellation (which every film program forms), and when trying to find out what they shared, some coordinates appeared.

The coordinates of this walk on a luminous geography were the film projectors and the Ceiba tree (Ceiba Pentandra). These coordinates, or cardinal points that emerged in my experience as a spectator -who now writes about what she saw-, are all the result of things that happened next to the films. That is to say, they were not objects properly or events that happened within the stories but were things that, while the films were happening, were also happening in all the life that revolved around them.

As I write, I review my few notes about each movie in my notebook. I didn’t say much because I wrote about the people sitting next to me, about the humid climate of a body of land surrounded by a huge body of water, about the power outages, and the snails I saw offered on the roots of a tree in front of the necropolis.

I feel that I am groping (in Spanish, the verb is “tantear”) with my hands, the shape of the words.

I searched the internet for the etymological root of the word “tantear” in Spanish:

“The word “tantear” has the meaning of “to calculate an amount” and comes from the suffix -ear (used to create verbs from nouns) on the word “tanto” and this from the Latin tantus = “quantity, number, portion”.” (own translation)

The word “groping” led me to the word “tentacle” (in Spanish, both have common roots):

“The word ‘tentacle’ comes from the Latin ‘tentaculum,’ which refers to certain animals’ tactile and prehensile organs. The word is formed with the suffix ‘-culum,’ over the root of the verb ‘tentare’ (to feel, to grope). This verb ‘tentare’ has a double origin, as it is both a vulgar form of ‘temptare’ (to attempt, to grope, also to touch and feel) and a vulgar iterative form of the verb ‘tendere’ (to extend, to stretch, to direct towards)”. (own translation)

I tend to head towards the light, with all my mobile limbs, with this tentacular writing, with this animal body with which I always touch life.

Through a crack, little by little, a strange animal appears, little by little. It is a film that approaches, it is an animal that wants to be taken care of. It wants to be fed. And then it falls asleep.

Two spots are drawn on the skin of this mammalian animal (although sometimes it is a bird, sometimes an amphibian, sometimes an insect). Spots that, like the lines on the palm of a hand, tell me the following about this Latin American map of movies (or dreaming animals):

- The Ceiba tree: And suddenly, those suspension bridges that we call movies appear.

In some Andean communities, the verb ‘criar’ (to raise) describes various occupations. For example, cultivating the land is a kind of mutual nurturing. It’s a shared caretaking process where the land is worked by a body that gives it time and patience, and in return, it offers something beautiful, like a squash.

Care and attention interweave a complex fabric of living relationships, crafts, are mutual nurturing. Elvira Espejo wrote Yanak uywaña to refer to the mutual nurturing in the artistic work.

I think of all the mutual nurturing: the mutual nurturing of the word, the mutual nurturing of weaving, the mutual nurturing of light. With the latter, all the sounds of a movie theater keep appearing in my head: bodies breathing, shouting, clapping or falling asleep. Something strange in that dark space invites us to gather to have a light source illuminate our faces. I think of all the motivations that can motivate one to go to a movie theater. I try to think a little bit more, tracing what could be that mutual nurturing of light. I almost always come back to the same idea: to meet with several people in the same space. Once again, I believe what intrigues me the most about cinema is what happens around it.

If the place of power is to deny the encounter

then what are all these bodies together in a room?

almost as if we were raising-mutually-a-mystery

All the signs of the films seen remain on these hands that write. The film appears, showing me its seed body. One of the days, after a lot of walking, I went late and by mistake I attended one of the screenings, which was another film I had planned to see.

This was the image: The night sky from the Amazon in Brazil.

What I saw: A lot of stars.

Where I was standing: An island, all surrounded by sea.

The image of the sky was followed by the image of a giant Ceiba tree in the jungle.

Outside the cinema, very close to it, there is a beautiful Ceiba tree, and sometimes people gather and leave offerings in its roots. Coconut. Sea snails. Sacrificial pigeons and chickens. The Ceibas have impressive roots, which connect with other things that are surely in the afterlife, like subway bridges. When I think of people leaving things at the root of the Ceiba, I also think of a mutual nurturing of the spirit. I see the tree in the streets of Cuba and on the screen of a cinema in Havana, and I think: They both have in common to gather a group of people to raise a mystery. Both people believe in something.

Sometimes, it seems that it becomes more difficult to believe in something with time.

To believe in something, like, for example, movies.

Or whatever it is that they generate.

However, the mystery re-emerges: the Ceiba and the film have in common that they are a bridge between two worlds.

- The projectors: The spiral temporality, the light coming from behind our backs.

In “The history of the gaze”, old Antonio, an indigenous man from the mountains of Chiapas, tells how the first men and women did not know how to “look”, even though they had eyes. Although they had the organs to see, they lived stumbling and bumping into each other, not knowing how to use their eyes correctly. The gods, responsible for the creation of the world, realized this evil and taught the first humans to look: not only to see, but to understand what they observe, to look at the other, at the heart of the other, and to recognize the look reflected in others.

The conclusion of the story is that one learns to look by looking at the look of the other. That is to say, looking is not something you learn alone. To learn to look, you have to do it in the community.

The films always give us back their gaze

they are the look of the look of the other that we

as spectators

are watching

cinema reminds us that light always enters through the cracks

through the cracks with which we have learned

to name the world

and there is a relationship of love

between this language, this life and this light of the films.

it is a mutual nurturing which sustains the mystery of learning to look at the other’s look.

looking at the look of the other

As I browse the book from which I took the story “The Story of the Gaze”, many snails appear in the drawings that illustrate it. Trying to look up the meaning of these, I found a note I took out of a book (I don’t remember which one):

“Snail is the paradigm of the symbolic thought of the Mayan people. When the universe and time burst out of the darkness and formless chaos simultaneously (in a correlation that Einstein reminded us of), even before the corn man populated it and the sun shone, the snail suddenly emerged with its bundle of years. That is to say, with the markers of time that we call calendar, and establishing the concrete time that we call history to reappropriate the world.” (own translation)

The snail presents us with a different form of time: forward, instead of the future, goes the past because it is what we can see. Behind, in the back, goes the uncertain future. That is why the children are carried there, hanging, ahead of time. But as everything is a spiral, the front and the back are reversed, or even sometimes, the back becomes the right side, the left side becomes the front, and all the cardinal points become one and the same: a bundle of years in the form of a spiral.

I think again of our bodies sitting in a movie theater: in the back, there is the projector, and in the front, there is the screen. Right in the middle are us, our bodies, which are like the threshold through which the light of cinema passes. Perhaps it is because the body was the first camera and our photosensitive skin harbors phantasmagorias of light. I try to arrange this geography of the cinema on the snail: the projector is the future, and the film’s image is the past. Once again, the bridges of a light that palpitates emerge in a subterranean way, with light communities that exist as long as the projection lasts.

Perhaps the cinema can still be that, a hope.