The Singing Blackbird

“Once Upon a Time There Was a Singing Blackbird“

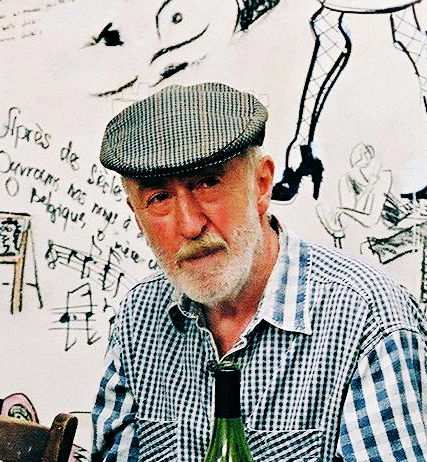

A Short Letter About Otar Iosseliani

By Salome Kikaleishvili

Shortly before his death, I caught a glimpse of him not far away from his home. He was led by his daughter, Nana, walking arm in arm, slightly hunching over, taking small tardy steps down the sidewalk. They turned into a dark archway, and the tall black contours of a man seemed even more drooping in the low-key lighting. I copped out of approaching him, fearing that it would ruin this magical black-and-white shot. This reminded me of Once Upon a Time There Was a Singing Blackbird – my favorite among his films, one with a nail hammered into the wall and the tickling of a clock.

Learning of his passing once again brought back the memories of Once Upon a Time There Was a Singing Blackbird, inspiring me to put it on and muse over time. He returned to Georgia almost 2 years ago – returned quietly, without fanfare. References to France as his “second home” irritated him. “I have one home, Georgia,” he would brush everyone off. “I just work, make movies in France. When I am not able to shoot films anymore, I will return”.

He was forced to move to France to work and make movies in the 1980s. His films made in Soviet Georgia were threatened with banning or “burning,” while the director himself often ended up doing what he hated so much, wasting time and answering dumb questions from dumb functionaries. Hundreds and thousands of letters and article were written to assert that Iosseliani was an embarrassment to the country, and its Socialist people, that “this is not what we are,” that “this is not how Georgians behave.” And yet, even the shorts and feature films he made in Georgia alone would have been more than enough.

Before filmmaking courses, there were mathematics and music schools of higher education, two professions that made their presence felt in his polyphonic cinema, in which there is no time or place, no climax or tension. Everything in his films is so simple and light, it seems as though Iosseliani – like Gia, the main character in Once Upon a Time There Was a Singing Blackbird – were sitting by the window, documenting things with a camera instead of a telescope.

Above all else, Otar Iosseliani was an observer.

Starting from his first film, he always worked with storyboards. A film in its entirety would be sketched out in detail, a task that later involved help from his daughter, artist Nana Iosseliani, who plays Eduki in the movie Pastorale. Actor gestures, internal framings, and camera movements would be defined down to the grad. Before setting out for principal photography, he and his long-time cinematographer, William Lubtchansky, would go through every detail in these “pictures,” ultimately transforming black pencil drawings into onset cinematic images. He would go through his address book in search of characters for his movies – reluctant to work with professional actors, he would say that they tend to ruin films. He had it all worked out on the set and took part in every aspect. He spoke individually with every actor – or maybe we should call them “film participants” – explaining who was supposed to play one role or another, how they were expected to walk, make a turn. And he demonstrated it all for them in person. “Here we are, Otar!” his old friends would say on the set. “What you want us to do?” “Nothing much. Let me have a smoke and I’ll show you.”

As a rule, filming involved a coterie of old associates: the director of photography, gaffer, sound mixer, also production designer Manu de Chauvigny and the scraggy and skinny Carpentier resembling a Modigliani painting, all doubling as actors once in a while. For him, filmmaking was about interaction with friends and like-minded people. He used to say, I make films for my friends.

He told me once that Alexandre Dumas had a habit of jotting down exciting stories on a handkerchief and then integrating them into his novels. I remember how Iosseliani himself kept stories on pieces of paper in the drawers of his big desk in Paris. Before tackling each new movie, he would pull his black notebook from one of the compartments, spreading the stories contained therein like solitaire cards and taking his time contemplating them, with some stories eventually taking part in the new movies while others disappeared back into the drawer.

In 2005, I attended one of his filming sessions. The movie was called Gardens in Autumn (“Jardins en Automne”). I never heard him raise his tone or being rough to anyone, even when the performer did everything wrong for the 100th time. He never parted with his white flat cap and whistle throughout the shooting. “You see, one whistle, and everyone is in place,” he told me once after another deafening shrill. No walkie-talkies or radios. Sometimes, the whole crew would freeze in their tracks, with their hands over the ears and their eyes squeezed shut even before his whistle reached his lips. A short whistle meant “stand by,” while a long one meant “quiet on set, action!” He kept a bottle of vodka or cognac next to his director’s chair. Similar to his film characters, he too was fond of drinking, toasting, friends, and black-and-white photos of ancestors – and he was as honest and stubborn as his heroes.

Falling Leaves, Once Upon a Time There Was a Singing Blackbird, Pastorale, Favorites of the Moon, Chasing Butterflies, And Then There Was Light, Farewell, Home Sweet Home, Monday Morning – one simple story after another, characters taking a back seat to one another, and you too obediently go along with the author in this vicious circle that he portrays with sadness at times and a cynical smile at others. A laureate of Cannes, Venice, and Berlinale, and a repeated winner of the Louis Delluc Prize and the FIPRESCI Award, he was hailed as “the last of the Mohicans” by some and “a living legend of world cinema” by others. But he did not care a bit about these epithets, nor was it important to him where to display his yet another major award. Some he would stick somewhere quite awkwardly, saying that he had run out of room.

On December 17, everything ended just like it does in his movies, unhurriedly and leisurely, with an eye on time. I believe that, first and foremost, he himself stayed there as observer. The same vintage furniture around, and black-and-white photos of his ancestors on the walls of his home: his brawny father in a military uniform, portraits of his mother and aunt in long dresses, and then he himself, most likely 7-8 years of age, with a serious expression on his face, probably told to sit still for a picture. In this room, where he spent his final days, photographs are pinned to the walls to portray those with whom he has worked and whom he loved – pretty much everyone is here. Toward the end, after he lost the ability to speak, family members would put his films on video-player, so the film would run in loop on TV screen in the same room, close to his bed. The last night it was Falling Leaves.

Otar Iosseliani was buried without pomp, surrounded by friends and young filmmakers madly in love with his cinema, next to his parents, aunt and granny, in an old grave fenced with slightly rusted bars, in the old Vake Cemetery.

The world of film has lost a most unyielding and noblest enfant terrible.

Salome Kikaleishvili

© FIPRESCI 2023

FIPRESCI 100: Homage to Klaus Eder at the 42nd Filmfest Munchen

FIPRESCI Returns to the Mar Del Plata International Film Festival After 7-year Hiatus

FIPRESCI Concludes a Special Participation at 78th Cannes Film Festival

FIPRESCI Jury at the Montreal International Documentary Festival

FIPRESCI Announces a New Collaboration with Millennium Docs Against Gravity Film Festival

FIPRESCI Signs a MOU with the Saudi Film Commission

FIPRESCI Unveils a New Design to Celebrate 100th Anniversary

Directors Georgi Djulgerov and Mohammad Rasoulof Receive FIPRESCI 100 Platinum Award

Klaus Eder receives the German Film Critics' Honorary Award for Life Achievement

In Memoriam Umberto Rossi

In Memoriam Sadullo Rakhimov (1951-2024)

Discovery Award – Prix FIPRESCI 2024

Discovery Award – Prix FIPRESCI Nominees 2024

FIPRESCI at the Classic Film Marathon 2024

Aruna Vasudev, 1936 – 2024

Working Conditions for Film Journalists - A Venice Press Release

Grand Prix 2024 to Yorgos Lanthimos

The Warsaw Critics Project 2024

Mohammad Rasoulof Sentenced to Prison

Masterclass Malgorzata Szumowska

Belgium Critics Vote on the Best of 2023

US Critics Vote on the Best of 2023

The Singing Blackbird

Discovery Award – Prix FIPRESCI 2023

Michel Ciment's Voice