A Unique Cinematic Experience

Jóhann Jóhannsson’s feature debut, Last and First Men (2020), is an experimental work that uses black-and-white images, a beautiful soundtrack, and a captivating voice-over to address the circularity of history, the repetition of important events, and the finitude of our existence.

Though this was his first job as a director, Jóhannsson had an extensive career as a composer. He composed scores for over 40 films and received Oscar nominations for The Theory of Everything (2014) and Sicario (2015).

Sadly, Jóhannsson died in 2018 and was not able to see his film come to full fruition. His narrative domain and the inventiveness with which he composes the images (combined, of course, with an excellent soundtrack) evinces the loss of not only an excellent composer but, also, a talented filmmaker.

The film is a free adaptation of a book written by Olaf Stapledon in 1930. Stapledon’s work is considered innovative for proposing a dialogue between contemporary humanity and an advanced society that lives more than two billion years in the future. Written by Jóhannsson himself in partnership with José Enrique Macián, the script uses an idea from the book but transposes it in an unconventional way.

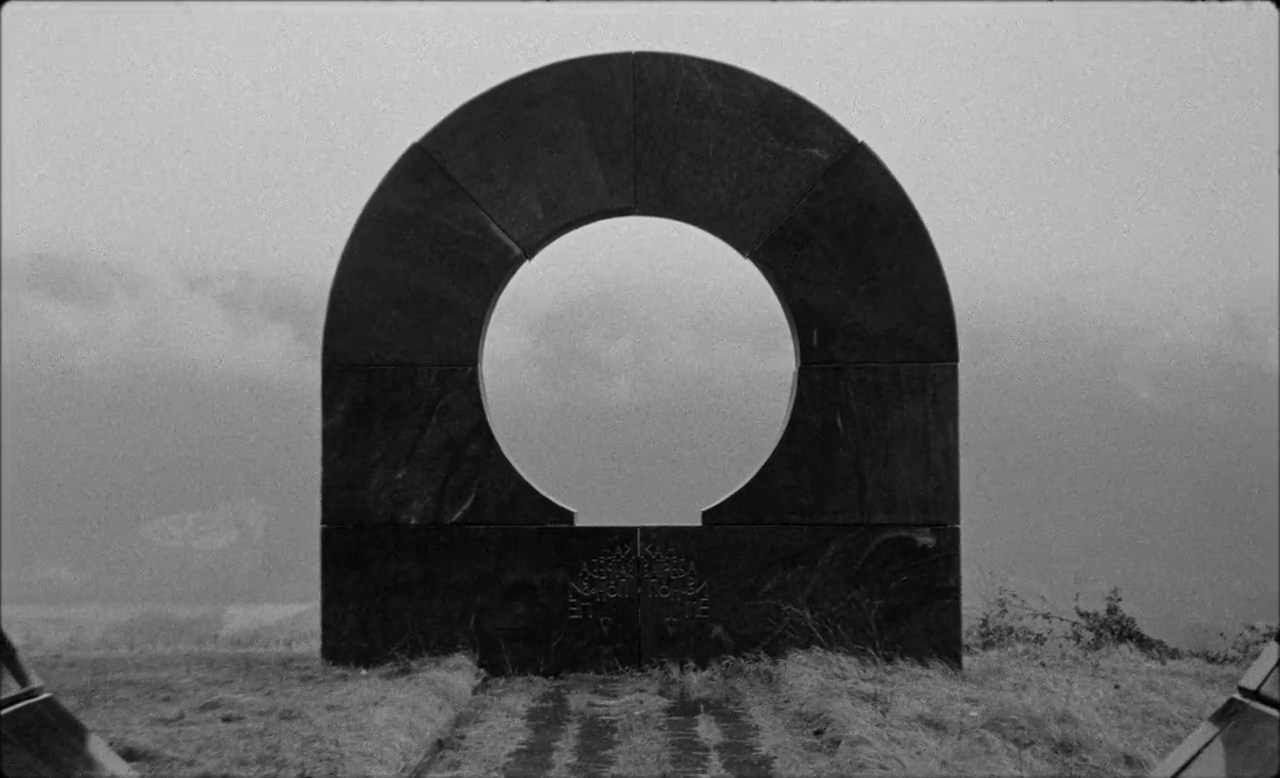

The plot is reduced to a narration performed by Tilda Swinton. The actress gives voice to an extremely advanced human race, passing on her knowledge, story, and experiences backward across time. But we never see these futuristic humans or their world; instead of showing images of tomorrow’s mankind, the director presents us with shots of an abandoned monument from ancient Yugoslavia, entitled Monument to the Revolution of the People of Moslavina.

With its distinct look, the monument was created by sculptor Dušan Džamonja in the 1960s and serves as a backdrop for Swinton’s monologue. It is notable, therefore, that the beautiful black and white photography (from the cinematographer Sturla Brandth Grøvlen) and the creative camera angles manage to give that place a futuristic and nostalgic aspect at the same time.

Past and present come together through this circular historical trajectory. As the film shows us, major events (and, in many cases, tragic events) tend to repeat themselves throughout history. It’s also remarkable how the film dialogues with our current pandemic reality: Last and First Men was made before everything that is happening in the world today.

The project was conceived and presented as a musical performance. At the performance, the mesmerizing images were complemented by Jóhannsson’s captivating soundtrack, performed live. After Jóhannsson’s death, image and music were united to form this movie. It is, therefore, a different experience from that envisioned by the director, but by no means a less impactful one.

As stated by Yair Elazar Glotman (co-composer of the movie), the world created by Jóhannsson is “broad enough and rich enough that everyone could kind of follow a single element or make their own connections and basically have their own experience and see something new every time you watch it”.

In his seminal article The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, German philosopher and sociologist Walter Benjamin introduced the concept of “aura”, used to define the uniqueness of a work of art. A painting has an aura because there is only one of it (all the rest are copies). A theater presentation too, because although the text remains the same, each presentation is unique.

The original project for Last and First Men had an aura. Each performance was its own snowflake. When transformed into cinema, the project loses its aura. But, as Glotman stated, the public’s perception is never the same. It is renewed at each screening and each revision. This is the timeless strength of Jóhannsson’s work.

Daniel Lucas de Medeiros

© FIPRESCI 2020

Edited by José Teodoro