Default Choices, or an Assertion of Preferences?

in 36th Ljubljana International Film Festival

by Shahla Nahid

International festivals are not merely cinematic meeting points, they also offer a window onto the state of the world and the individual concerns of its inhabitants. Through their works, directors of all nationalities deliver, often implicitly, a multitude of unspoken truths. When looking at all the films in competition—like a rubbing that reveals hidden patterns—recurring themes emerge which, far from reassuring, raise questions.

A clear trend has emerged over the past two or three years: Young filmmakers seem to be distancing themselves from major global issues—climate change, wars, the erosion of democracies, the rise of narco-crime, youth violence, or the lowering age of delinquency. Should this be seen as the effect of saturation in the face of an anxiety-inducing information flow, pushing them toward denial, or as a deliberate choice made by selectors? In both cases, the viewer is faced with works that leave them indifferent, as they reflect situations sometimes experienced even more brutally in his or her real life. Worse still, these films give the impression of belonging to a series or episodic format, always built on the same model.

A revealing selection: the Ljubljana case

The “Perspective” competition section at the most recent Ljubljana festival illustrates this trend perfectly: of the ten films presented, seven draw from the very personal experience of their directors, often centered on family conflicts in a bucolic setting (cats, dogs, roosters, fieldwork filmed ad nauseam). These narratives of survival and struggle against prejudice, set in closed and hostile environments, seem to choose attractive landscapes to divert attention from their cinematic shortcomings: unbalanced sequences, fragile scripts, shallow characters, and a lack of originality in visual language. Some films, such as A Sad and Beautiful World by Cyril Aris, struggle even to justify their presence in the section.

Works that are overly personal, with limited cinematic potential

Contrary to the norms which require putting the big winners of a festival at the top of the article, I would like to start with those that did not induce any particular enthusiasm. So, let us begin with the films that would benefit from substantial revision. At the top of the list is The Devil Smoke (El Diablo Fuma) by Mexican director Ernesto Martinez Bucio, which squanders a promising subject: Romana, forced to care for her five grandchildren abandoned first by their unstable mother and then by their father, instills in them a fear of the devil and drives them to live reclusively until social services intervene. The confused, scattered script is worsened by shaky handheld camera work, compounded by the incessant screaming of the children. The final five minutes attempt a conclusion, but the excessive use of poor-quality video footage and the imbalance among the film’s sections make any deeper reflection impossible.

A similar disappointment is Sandbag Dam (Zečji nasip) by Croatian filmmaker Čejen Černić, which attempts a parallel between an impending devastating torrent and the loss of Christian values through the homosexuality of its protagonists. Too many unnecessary details weigh down the narrative, the characters lack depth, and the soulless film seems to use a still-taboo subject to mask its cinematic shortcomings. Yet, despite the appeal of the theme—which often attracts attention and clouds the objectivity of audiences and juries—the absence of tension and the exhausting music make it a dull and unfinished work.

Blue Heron, by Hungarian-Canadian director Sophy Romvari, draws on her own childhood to depict an immigrant family in Vancouver whose balance is shaken by an asocial teenager.

Wind Talk to Me, by Serbian filmmaker Stefan Djordjević, revisits once again the mother-son relationship in a rural setting, while Traffic (Reostat), by Romanian director Teodora Ana Mihai, tackles a heist organized by Romanian workers in Western Europe without ever finding the rhythm or tension required for the genre. However, it is scripted by the important Romanian filmmaker Cristian Mungiu (4 months, 3 weeks and 2 days).

When talented actors save a film

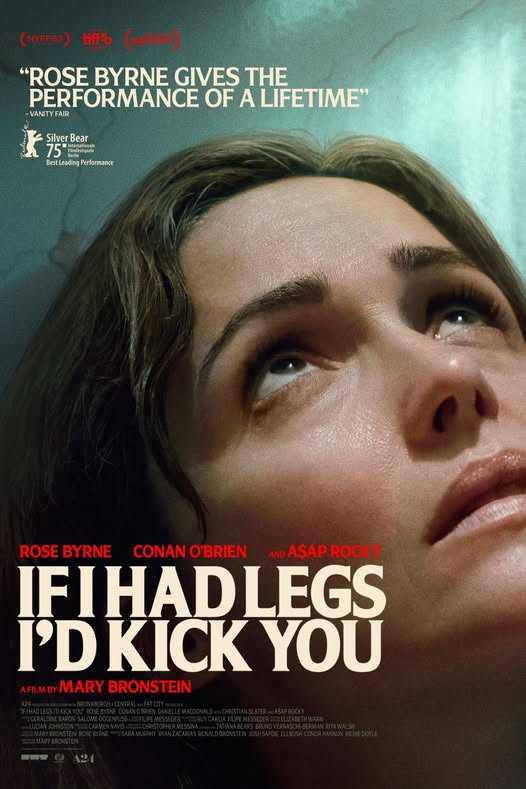

If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, by American director Mary Bronstein, captures attention thanks to Rose Byrne’s remarkable performance (winner of the Best Actress award at the Berlinale) as a psychotherapist tormented by her own demons. While the film once again explores the mother-daughter relationship, the child’s unnamed illness and the heavy-handed allegories (such as the vision of a hole or the tearing out of a tube) eventually become exasperating. Yet the mother’s determination to break the cycle of despair and reclaim her own lost childhood—symbolized by a reversal of roles—gives the film a poignant conclusion.

If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, by American director Mary Bronstein, captures attention thanks to Rose Byrne’s remarkable performance (winner of the Best Actress award at the Berlinale) as a psychotherapist tormented by her own demons. While the film once again explores the mother-daughter relationship, the child’s unnamed illness and the heavy-handed allegories (such as the vision of a hole or the tearing out of a tube) eventually become exasperating. Yet the mother’s determination to break the cycle of despair and reclaim her own lost childhood—symbolized by a reversal of roles—gives the film a poignant conclusion.

The award-winning film and its uniqueness

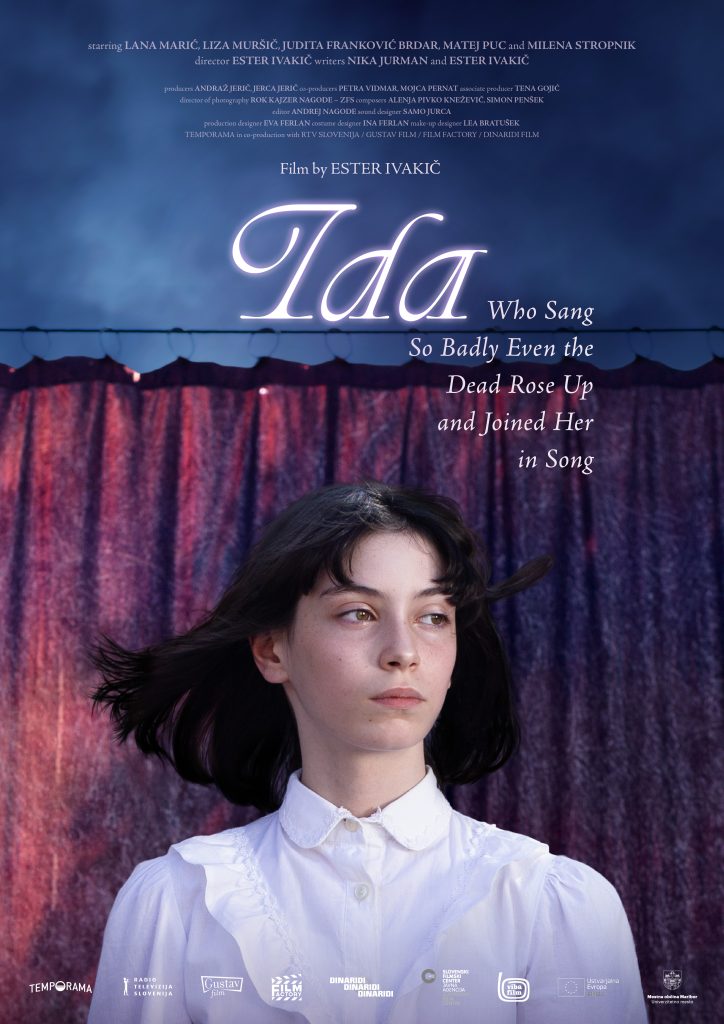

Ida Who Sang So Badly Even the Dead Rose Up and Joined Her in Song (Ida, ki je pela tako grdo, da so še mrtvi vstali od mrtvih in zapeli z njo), the first feature film by Slovenian director Ester Ivakič, stands out for its more universal questions: the relationship between life and death, set against a backdrop of family conflict and a fantastical tale. Led by a twelve-year-old girl, the film uses her discomfort within both family and school life to explore the absence of loved ones and the regret of missed opportunities. A subtle work that would gain greater prestige if it were not surrounded by so many linear, repetitive films.

Ida Who Sang So Badly Even the Dead Rose Up and Joined Her in Song (Ida, ki je pela tako grdo, da so še mrtvi vstali od mrtvih in zapeli z njo), the first feature film by Slovenian director Ester Ivakič, stands out for its more universal questions: the relationship between life and death, set against a backdrop of family conflict and a fantastical tale. Led by a twelve-year-old girl, the film uses her discomfort within both family and school life to explore the absence of loved ones and the regret of missed opportunities. A subtle work that would gain greater prestige if it were not surrounded by so many linear, repetitive films.

Peacock: refreshing originality

Peacock: refreshing originality

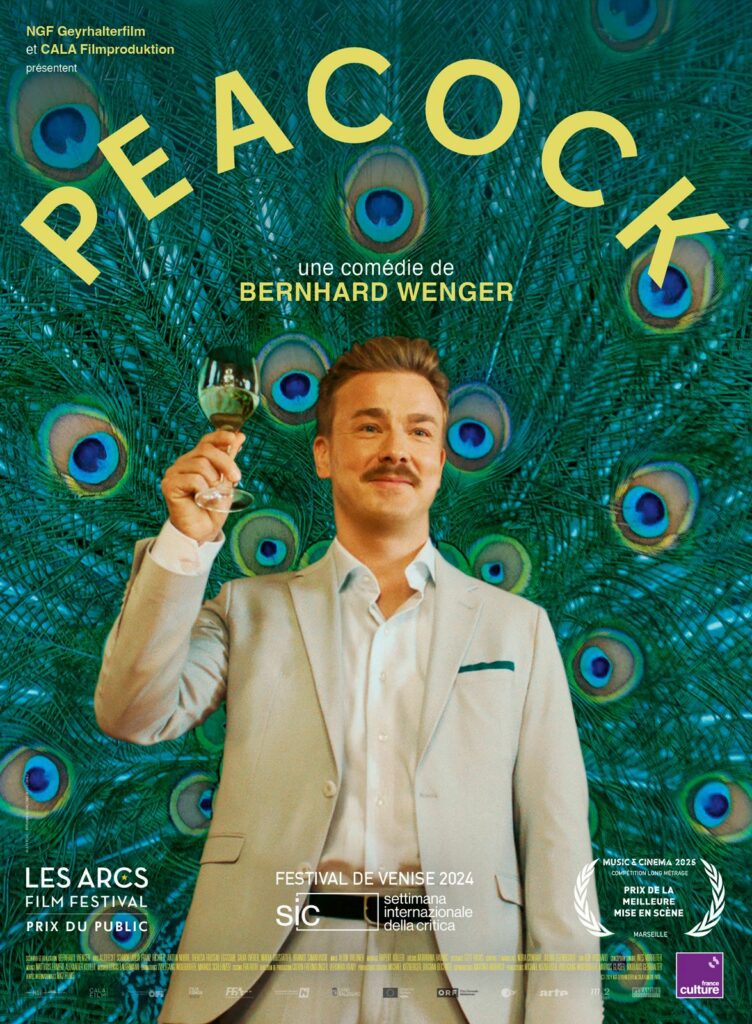

Peacock (Pfau – Bin ich echt?), by Austrian director Bernhard Wenger, stands out for its originality, cinematic mastery, and universal questioning: Who are we when we are no longer performing? This debut feature, rich in visual humor and unexpected twists, examines the excesses of modern society, where the pursuit of appearances leads to the loss of self. The metaphor of the peacock, which spreads its feathers only to seduce, is filmed with finesse. The satire—supported by evocative sets tied closely to the characters’ psychology and by the performance of Albrecht Schuch as Matthias—questions our submission to social roles and the resulting loss of authenticity.

What happens to Matthias, a coach “for all seasons,” a professional of “custom-made personas” who easily passes as many flawless characters? Like an excellent actor, Matthias excels at embodying borrowed identities. In fact, he has mastered the art of adaptation—until the day he breaks.

The film carries the viewer thanks to its fluidity, consistently steady pacing, meaningful sets, effective acting, and the camera’s constant distance, allowing the characters to remain part of their environment.

Peacock could easily have won the Best Film award jointly. Except that FIPRESCI regulations don’t allow it.

Growing Down: lying to save one’s son?

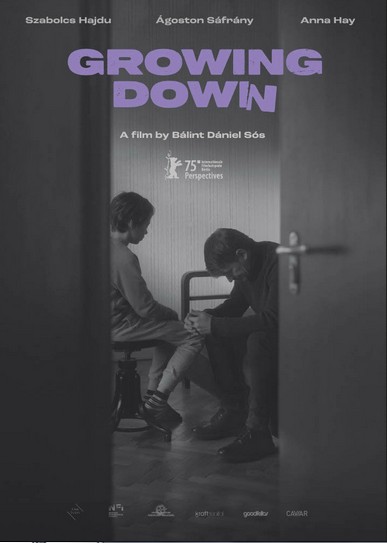

Growing Down (Minden Rendben), by Hungarian filmmaker Bálint Dániel Sós, again evokes family relationships but distinguishes itself through its minimalist visual approach, reminiscent of Béla Tarr. Shot in sometimes opaque black and white, the film plunges the viewer into the ethical dilemma of a widowed father faced with a deadly accident caused by his son. Without being a manifesto on judicial objectivity, it succeeds—thanks to a powerful final scene—in delivering a strong message: Be mindful of where you stand when judging wrongdoing, and beware of hasty conclusions. The long takes, thoughtful slow-downs and accelerations, and classical music contribute to a narrative that is both realistic and poetic.

Growing Down (Minden Rendben), by Hungarian filmmaker Bálint Dániel Sós, again evokes family relationships but distinguishes itself through its minimalist visual approach, reminiscent of Béla Tarr. Shot in sometimes opaque black and white, the film plunges the viewer into the ethical dilemma of a widowed father faced with a deadly accident caused by his son. Without being a manifesto on judicial objectivity, it succeeds—thanks to a powerful final scene—in delivering a strong message: Be mindful of where you stand when judging wrongdoing, and beware of hasty conclusions. The long takes, thoughtful slow-downs and accelerations, and classical music contribute to a narrative that is both realistic and poetic.

Conclusion: a subdued and mixed selection

Of the ten films presented, four were directed by women, so parity is broadly respected. Yet the total absence of Asia—a continent central to the global cinematic landscape—raises questions. None of the major countries whose works are usually ubiquitous at festivals and often win awards (China, Japan, South Korea, Iran) found favor with the selectors. With the exception of three films (Mexican, Lebanese, and American), the others came from neighboring European countries, creating a certain uniformity. Only Peacock stands out for its originality.

One question remains: does this “unity” in selection stem from limited access to available productions and proposals, or from a deliberate preference?

Shahla Nahid

© FIPRESCI 2025