Europe as Utopia and Destiny

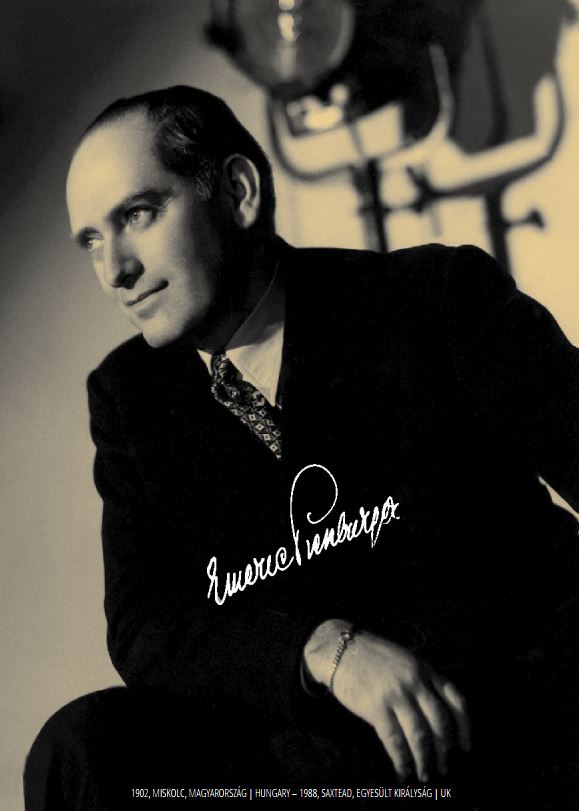

Emeric Pressburger

Europe as Utopia and Destiny – A Few Thoughts and Observations

A Prologue

Some decades ago, I sat next to an elderly and, quite obviously, refined gentleman on a transatlantic flight from New York. We came from very different fields of life. Before his retirement, he had been working as a technical engineer in Great Britain. During the flight I started browsing through the books I had bought in the States. One attracted my neighbour’s attention: a paperback edition of A Life in Movies, Michael Powell’s first autobiography. „I wonder if it says anything about Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff?“, the gentleman asked. How surprised I was that he should know this extraordinary name!

In fact, he had never been able to forget it since he first saw The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp in a London movie theatre – it must have been a revival in the late 1940s or early 1950s. He had been very taken by Anton Walbrook’s performance, and especially by his monologue when he applies for political asylum in Britain in 1938. His family had left Poland the same year – wisely before the German invasion one year later. He had no reason to sympathize with a German, a soldier to boot, but with this character he did. In fact, he identified strongly with him, because Kretschmar-Schuldorff was in the exact same position that his family had been in. I gave him the book to read, and he finally found out who had invented the fabulous name that had stuck in his memory. He also discovered that Emeric Pressburger was writing about himself when he created this character.

When Imre became Emeric

In his indispensable biography of Pressburger, Kevin MacDonald translates the first short story Pressburger published in German: Auf Reisen (in English: Travelling, 1928). It’s a whimsical, lighthearted piece about passengers flirting while travelling. Naturally, this sketch is a far cry from the spiritual journeys of A Canterbury Tale and I Know Where I’m Going!. But you can already find the germ for them here: the betrothed (fiancés and fiancées, husbands and wives) are absent in the short story as in the two films, and the journeys become opportunities for romance and even seduction. Notably, on a few pages it tells a story within a story – already a hint of the self-reflecting examinations of storytelling that will occupy him later with Michael Powell.

Pressburger learned the screenwriting trade when the German film industry was at a turning point: the arrival of sound. He worked on about a dozen films during his stint at UFA, some of them multi-language versions of the same films that were common in the early days of sound. His command of several languages came in handy. Also, his early films already transcended cultural borders.

He also found lifelong friends at UFA, among them the producer Günther von Stapenhorst and the composer Allan Gray. He worked mostly on (musical) comedies. His outstanding screenplay of this period however is a dramatic film. Farewell (Abschied, directed by Robert Siodmak in 1930) takes place entirely in a boarding house in Berlin where several destinies and storylines cross. The characters live only temporarily in these cramped quarters. In other words: they don’t have a home. It is an ensemble piece that respects the unity of time and space. It makes inventive use of sound. There is a vivid cacophony of voices and urban noises in the boarding house that makes the film an early masterpiece of atmosphere. Kevin MacDonald regards Farewell as one of Pressburger’s most experimental films – of which there would be many more to come.

Child’s play

In Germany he collaborated twice with Erich Kästner, who was already famous for his children’s books. Unfortunately, I’d Rather Have Cod Liver Oil (Dann schon lieber Lebertran, 1931) – a short film and the directing debut of Max Ophüls – is lost. But the storyline shows Pressburger’s penchant for anarchic fantasy. Actually, it is his first foray into heaven: A boy’s prayer is granted, and the roles of children and adults are reversed. While his parents go to school, he smokes a cigar after breakfast.

The second film is a classic from 1931: an adaptation of Kästner’s novel Emil and the Detectives (on which the young Billy Wilder worked as well) about a young boy from the country whose money is stolen on the train ride to Berlin. There, he befriends a gang of youngsters that already foreshadows the adventurous children in the Powell & Pressburger films, for example the kids playing at battle in A Canterbury Tale (1944).

Powell & Pressburger’s collaboration came full circle in The Boy Who Turned Yellow, the last film they made together for The Children’s Film Foundation in 1972. In this strange mixture of magic and realism, the world of the children and the world of the adults are distinctively apart.

In Pressburger’s novel Killing a Mouse on Sunday, adapted in by Fred Zinnemann in 1963 as Behold a Pale Horse, this alienation is tragic. The resistance fighter in exile doesn’t believe the young boy warning him to go back to Spain. The boy is central to the story, he carries its moral weight. His plight is drawn great empathy: an orphan who wants revenge for the assassination of his father and is in search of friendship.

Target for tonight: Stuttgart

Powell & Pressburger were famous – and infamous – for creating charismatic or even likeable German characters. Pressburger knew the country well, he felt obliged to make a distinction between German culture and Nazism. That took courage in wartime. The films were even more daring than that.

Both The Spy in Black (1939) and the The 49th Parallel (1941) are told from the point of view of German invaders. Conrad Veidt as the captain of a German submarine is not yet a completely sympathetic character but ambiguous enough. He displays decency and a code of honour in the end and almost becomes a tragic figure.

The captain of the Panzerschiff Graf Spee in The Battle of the River Plate (1956) is an epitome of this ambiguity. A confirmed patriot, he takes a difficult decision that is bound to make him fall out of grace. He sacrifices his ship, because he would rather be responsible for a thousand surviving seamen than have a thousand dead heroes on his conscience.

On the other hand, isn’t it interesting that heaven in A Matter of Life and Death (1946) is populated only by soldiers from France, Great Britain and the US? No German seems to be allowed in!

(A Footnote: The mission to bomb a German city in One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942) takes the crew not to the more strategically decisive targets Berlin, Hamburg, Dresden or Cologne, but a city in southern Germany that played an important role in Pressburger’s early travels and travails: Stuttgart.)

Resistance and bonding

One of Our Aircraft Is Missing deals with the resistance movement in the Netherlands – which is a rather uncommon subject; resistance in France or Germany itself are a much more prominent subject in war films. Powell & Pressburger continuously broaden their perspective on Europe. On his own, in his novel To Kill a Mouse on Sunday – the basis of the film Behold a Pale Horse – Pressburger treats the resistance against fascism in Spain, another chapter of European history that has been largely neglected by the cinema.

With the notable exception of Clive Wynne-Candy in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), Powell & Pressburgers soldiers are ready for peacetime. They fulfill their duty but are able to look beyond it. Also, they never stop being the people they were before the war. One of the best examples is the GI from A Canterbury Tale who comes from a family of lumberjacks and befriends a local woodcutter and carpenter.

Pressburger’s characters have a talent for spontaneous bonding. The Spanish resistance fighter in Killing a Mouse on Sunday, a confirmed atheist, bonds with the catholic priest. They are antagonists, but share a moment of camaraderie when they realize they grew up in the same town in northern Spain. The most beautiful bonding is, of course, the friendship between Clive Candy and Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff. And above all, the one between Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger.

T’is better to miss Naples than hit Margate

The crew of The Archers was famously assembled among emigrés: composer Allan Gray hailed from Austria; art directors Alfred Junge and Hein Heckroth were German, as was cinematographer Erwin Hillier and were the actors Walbrook and Veidt. They unavoidably and proudly brought a continental sensitivity to the British film industry. The Archers were instrumental in establishing the exile community as an important, vital part of this industry (Pressburger also supported fellow screenwriter Carl Mayer financially when he fell on hard times in England).

It certainly helped that Alexander Korda was such an influential and powerful player in the business. But Powell & Pressburger went even further in their desire of opening the British mindset: They made an immense effort to strengthen Anglo-American relations in their war films. This relation is often challenged and seldom harmonious – they made no clear-cut, simple propaganda films -, but the treatment is always respectful of national identities and perspectives.

How to be an alien

As a foreigner, you often see the idiosyncrasies of a people much clearer. You are struck by particularities that seem self-evident to the natives. But I can’t think of another screenwriter in exile who was so extraordinarily alert to British lifestyles, mores, social rituals, customs and folklore. He is clearly fascinated by them, as well as by national identity and the class system. (Just think of the distinction Torquil makes between „poor“ and „not a lot of money“ in I Know Where I’m Going!.)

Pressburger’s screenplays are especially sensitive to language, to figures of speech and to their local diversity. Very often, they are not taken for granted. The „landgirl“ from London and the American GI in A Canterbury Tale have a hard time understanding the people in Kent; Joan Webster in I Know Where I’m Going! (1945) is confronted with an exotic language (Gaelic) once she arrives in Scotland.

The two films have a sense of place that is extraordinary. Just compare the two with The Spy in Black and you’ll see what progress they made in terms of rooting their stories in their respective locations. The two later films seem to be populated by characters that really live there. Of course, Powell knew them intimately; he was raised in Kent. Pressburger seems to have been a miracle of cultural assimilation. But it also took his outsider’s point of view to create this magical sense of place – and the impact it has on characters.

The screenwriter deeply understands the experience of exile and the longing for home. The „frustrated“ journey to Kiloran in I Know Where I’m Going! is really a metaphor for both: Joan wants to reach an island and can’t; Torquil wants to reach his home on the island and can’t either. But that’s not just a question of metaphor. It is very concrete and visual because of Pressburger’s lyrical alertness to the beauty of the landscapes. Kretschmar-Schuldorff’s monologue about feeling homesick for his wife’s homeland comes straight from his heart: „Very foolishly, I was thinking of the English countryside“.

Mainstream Avantgarde

The inventiveness of the Powell & Pressburger films knows no limits. The narration of A Matter of Life and Death even opens from a cosmic point of view! It has always my conviction that they made experimental films in the realm and in the confines of narrative cinema. Experimental films about light and darkness (A Canterbury Tale), about colour and black & white (A Matter of Life and Death), about atmosphere and its seductive, transformative power (I Know Where I’m Going! and Black Narcissus), about time and memory (The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp), about sound and silence (The Small Back Room). The list goes on and on: they defined in a new way how ballet and opera can be shown in cinema etc.

Their visual inventiveness is widely celebrated. But I think it firmly has its basis in the writing they did together. Their magical timeskips (or time warps) like the one in the Turkish bath in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp were written first and directed second. Another example is the cut from the falcon to the aircraft at the beginning of A Canterbury Tale: It allows the film to pass over six hundred years in history. It also prefigures the famous moment in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey when the monkey’s bone transforms into a spaceship. Powell & Pressburger knew every magician’s trick in cinema.

Leave out the indispensable

French director Bertrand Tavernier once confessed to me that he made every film thinking of Powell & Pressburger. They were responsible for his strategy to become the producer of his own films. They influenced his mise-en-scène in a profound way. The colour palette of Tavernier’s Life and Nothing But (La Vie et rien d’autre), a film from 1989, is informed by the use of technicolor, especially in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp: Start with muted colors and then introduce the bright and strong ones.

But an even more decisive one seems to me the eccentric, whimsical structure of the screenplays, their nonchalance and their daring conversion of narrative conventions. They rely on bizarre ideas as plotpoints (like the „Glue man“ in A Canterbury Tale), they mix genres, fantasy & realism, comedy & seriousness; A Caterbury Tale is in parts a detective story.

What Powell & Pressburger taught Tavernier most of all: Skip the indispensable scenes! There is a joyful, enthusiastic irresponsibility to their storytelling. They create suspense for five minutes in the scene before the duel in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp – and then, once it has begun, the camera pans outside and leaves us guessing what the outcome might be. The ellipses, the holes in the stories are daring; they create curiosity. Towards the end of The Battle of the River Plate they lose sight of their nominal hero – the German captain – for almost half an hour and switch to the perspective of the British navy. After that, we look at the captain with different eyes.

The most profound impact of this nonchalance on Tavernier’s films can be seen in Safe Conduct (Laissez-passer) from 2002 . The changes in tone are pure Emeric Pressburger, the film switches from the dramatic to the comic, from the heroic to the trivial, from the sublime to ridicule. It’s maybe no coincidence that it tells a story of resistance against fascism – in this case, the Nazi occupation of France.

An Epilogue

The Polish-British gentleman I met on the flight from New York to Europe really used the long hours well. He took his time to read extensively in Michael Powell’s memoirs. One observation impressed him above all others. At a certain point, Powell writes, his friend Emeric refused all the invitations he received. As an exile he had been the guest too long – now he wanted to be the host. My neighbour understood that very well.

Gerhard Midding

© FIPRESCI 2022