Can a robot be a true companion to a human? What is the connection between man and machine? Android Kunjappan Version 5.25 (2019) poses these questions in a humanistic, gently humorous way, and invites us to explore and speculate, and come to our own conclusions.

The film, which won the FIPRESCI award for the Best Debut Malayalam feature at the recently concluded IFFK ( International Film Festival of Kerala), is based in a small Kerala village. That makes the location extremely specific in terms of the culture, apparel, and other accoutrements. But the idea of empty nests, ageing parents, and the impact of loneliness, is universal. Who doesn’t dread leaving the elderly to their own devices? Ageing comes with some certainties, and not all are pleasant : the possibility of debilitating illness invariably weighs heavily upon adults having to live and work away from home.

Bhaskara Poduval (Suraj Vejaramoodu), refusing to age gracefully, is beset by the fear of dying alone. His son, Chubban (Soubin Shahir), shackled to the old man who refuses to leave the homestead, is left scratching his head. The solution is unexpected but perfectly apt : the human droid Chubban is assembling in a Russian city, is able to function as a home nurse. Why not place one such droid in his own home? The idea comes from the pretty Hitomi (Kendy Zirdo) a half-Japanese, half-Malayali colleague. In the faraway town, the two strangers from different parts of the globe find themselves drawn to each other : he is amazed that she speaks Malayalam ; she likes the fact he is so invested in his father’s well-being.

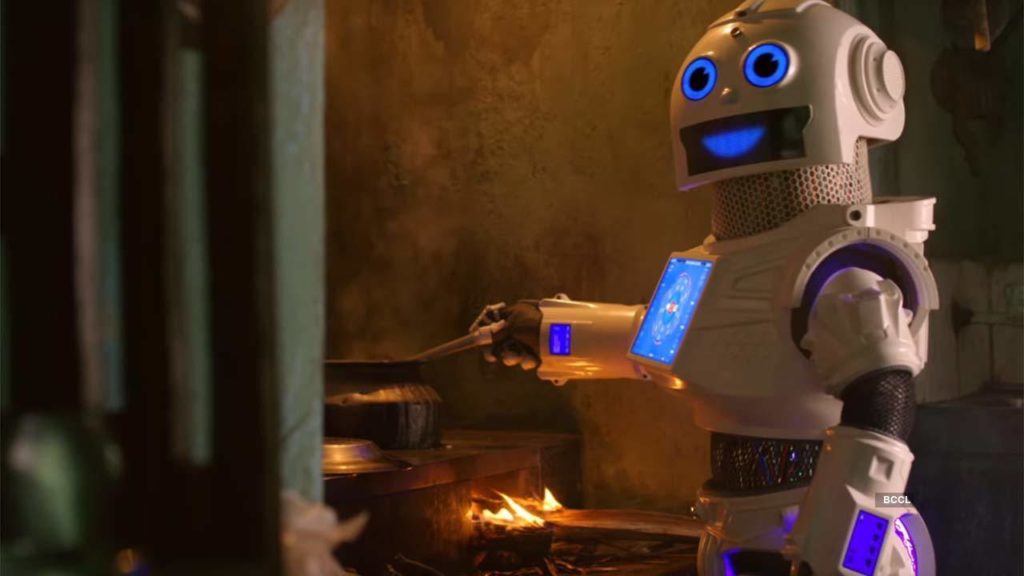

The most endearing part of the film, directed by Ratheesh Balakrishnan Poduval, comes from the interludes between the irascible, grizzled Bhaskara and the ‘cute’ android, whom he starts calling Kunjappan, a generic Malayalam endearment for ‘little one’. Kunjappan not only helps the old man with the activities of daily living, he becomes the eyes and ears of Chubban, who is able to ‘see’ his father through the droid’s computer generated information circuits.

The inevitable jealousy that can arise, even from the most unexpected quarters, is the fulcrum on which the film pivots. How can Chubban, despite all his adult rationalisations in place, see his father’s affections focussing on what is, essentially, a machine? It’s also interesting how we, the viewers, are seduced by the old man’s growing fondness for the android, whom he has begun treating as a son. We know that Kunjappan is a machine, but we can’t help smiling when we see the droid dressed as a young Malayali fellow, a ‘veshti’ draping his lower body. If we can attribute human qualities to animals, why can’t we extend the same courtesies to a machine which appears to have more empathy and emotional intelligence than most humans? The way the film ends is a tad clunky, but for most of its duration, Android Kunjappan Version 5.25 does justice to its thought-provoking premise.

In one of those co-incidences that are so much a part of the movie-going universe, I watched a film at the recently concluded Berlinale, which has a similar theme. ‘I Am Your Man’, by Maria Schrader, dangles a handsome droid in front of a highly educated social scientist whose work involves excavating the past. It is her present that’s more concerning for her, however, when she finds herself confused and bewildered by the closeness she starts feeling for Tom. What’s the point of a perfectly cooked egg, which Alma spends so much time boiling to a perfect hardness, for an entity which doesn’t eat?

The resolution in both films is different, but what stuck me is the core similarity. The need for humans to make connections is primal. So what if it is a machine that will fulfil those desires? And an even more vexing, deeply philosophical question : will there be a time when we can’t tell the difference?

Shubhra Gupta

© FIPRESCI 2021