The Persistence of Rituals

Trying to find aspects that crossed the grid of films during the 71st edition of the International Filmfestival Mannheim-Heidelberg, an element that began to acquire a certain density in my memory was an idea of the spiritual, which appeared broadly but persistently throughout the works of several authors.

The “spiritual” seems, and is – especially in current times, dominated by a resurgence of New Age eclecticism – an unreliably broad concept, since it embraces variants that can encompass things as dissimilar as institutionalized religion, astrology, the use of designer drugs, neo-hippie currents, diets, gestalt psychotherapies or business oriented mindfulness seminars. That is, the threshold of its semantic load runs the risk of extending as far as one wishes. However, digging into this term a little more, what caught my attention the most was not so much this quasi-mystical condition, but rather the ritual character of a lot of symbolic and repetitive acts scattered throughout the films. Thus, in the movies, but also in life, more than a pre-existing, ex-nihilo spirituality, there is something in the exercise of certain practices that shape these experiences -or even more, that create the necessary conditions for them to happen. A bit similar to the famous phrase by Blaise Pascal quoted by Louis Althusser of ” if you want to gain faith, act as if you believe, pray, kneel down, and you will believe, faith will come by itself”, these rites, in their repetition or in their performativity, not only provide the necessary conditions for the spiritual to appear but also make up its very texture, its true density.

Among the 18 nominated films, the rites are far from having a common root, and many times they touch on different aspects that can include the religious, the political, or the familiar. Of all the films, the one with the strongest symbolic charge was You Won’t Be Alone (winner of the first prize of the International Jury). In a strange middle ground between the quasi-ethnographic thoroughness of Robert Eggers (as he did, above all, in The Witch) and the poetic and cosmic cinematography of Terrence Malick, the film recreates a Macedonian myth, in which a witch marks a baby from birth, endowing her with shapeshifting abilities that will take true form in her 18th birthday. Most movies would focus on the most powerful and tragic meaning of this power, but in the multiple incarnations of this young woman—taking the form of wolves, cats, girls, and men—the film ends up being a grueling essay on life, resilience and cruelty. Thus, in several of the transformations we can see, as in a longitudinal cut through ages and times, the difficulties and dangers of being a woman, but also of being a peasant. Perhaps too dependent on its poetic voiceover, the film’s high points are found in the POV cinematography of different beings, as well as in the bloody but at the same time the natural condition of the rite of penetrating the skin and heart of the new vessels before arriving at a new transformation.

Another film that revolves around a mythical quality is El Agua, where director Elena López Riera takes a semi-documentary stand on a group of young people from the impoverished southeast of Spain. In the film, through these naturalistic depictions of the teenage girls, she starts to delineate some archetypical dimension of femininity as something also fluid and moldable as the title’s element. There, what seems to be a precise cut of a coming-of-age story takes on other shades between the poetic and the dirty, like that stream that carries the stinking corpse of a goat in its current, or that rain that devastates an illegal electro rave where everyone seems immersed in their true and ecstatic ritual.

Another film that encompasses this kind of religiosity with more current practices is The Portuguese Wolf and Dog, also a kind of sexual awakening film, which intersperses scenes of local religious processions with hyper-aesthetic drag queen acts. One of the great achievements of Claudia Varejão -similar to what Elena López Riera does- is being able to capture that mythical substratum with elements of everyday life, turning a roller skating scene in a semi-abandoned rink into a poetic and transcendent act.

It should be noted in this selection that all these ritualistic dimensions are traversed by something clearly political. Perhaps the film where this issue is most underlined is Ashkal, a police thriller set in Tunisia, where a strange series of suicides by self-immolation begin to make their way into the news. These crazy acts contain echoes of some famous Arab Spring protests, but in the film, the deaths are devoid of any explicit claim, which leaves the detectives baffled. Eventually, the film finds a mysterious villain, a man who manages to hypnotize his victims to make themselves set on fire. In this twist, which in its icy tone is reminiscent of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure, the increasingly relentless ritual makes one remember “The Things We Lost in the Fire”, the brilliant short story by Argentine writer Mariana Enriquez, where a group of women victims of domestic violence set themselves on fire to produce through their disfigurement an allegation more powerful than all the words and actions poured out in the public opinion. Thus, just as the wood contains within it the fire that is crouching down to come out, the film holds in the image of that gigantic final pyre, a much broader and more enigmatic meaning of political content.

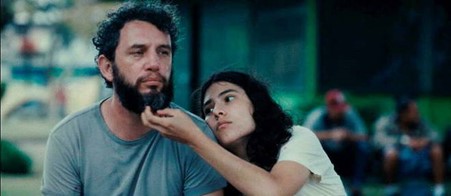

Another movie that combines mysticism with politics is Clément Cogitore’s Sons of Ramses. In the film, a kind of con artist who contacts deceased relatives for money (resorting to gadgets from social networks and previous research), begins to come across a true religious experience from the irruption of a group of poor young delinquents who storm into his apartment. At first I noticed in this film an uncomfortable incongruity between the editing and the claustrophobic spaces of the building. There, people constantly appeared from one window to another and everything seemed to have a spatial disjointment, as if there were film or script wormholes between one wall and another. However, as the film fermented in my memory, I began to understand that these apparent shortcomings contained a metaphorical charge. By these means, the intricate maze of rooms that take form in that building in which the protagonist advances ends up giving shape to its own spiritual byways. Thus, the anti-hero of Sons of Ramses has to go up, as if he were in a video game, through various rooms and stairs until he reaches the roof. A path from the basement of deceit to the roof of enlightenment.

Rites worm their way even in minuscule stories centered on the familiar. The Costa Rican I Have Electric Dreams is a powerful portrait of violence passed down from generation to generation. Between poetry, abuse and bipolar disorder, the relationship between the young protagonist and her father takes a definitive shape in the tests of pain resistance that persist between her sister and her. This act, in which the girl cinches her sister’s hair, explaining to her that the pain doesn’t really exist, that it is merely something psychological, is one of those small images that seem to contain a whole universe within, a repetitive act that drags on for years. parents, grandparents and great-grandparents passing down this pain as if it were a hereditary disease.

Finally, The Maiden -the film that the FIPRESCI jury unanimously recognized as the best work of the festival- is one of the most profound and effective portraits of the process of mourning in recent years. Shot in an immersive 16mm where everything takes on an almost palpable texture, the film follows the lives of two skateboarders who roam the forested city of Calgary, Canada, performing various stunts and tagging abandoned buildings. Until then, the structure and visual elements are reminiscent of the Serbian Tilva Ross (Nikola Lezaik, 2010) but when one of the two boys is run over by a train, the film takes another path. There, debutant Graham Foy follows in the footsteps of the survivor and the ghost of the deceased, but filming them in the same floating, almost evanescent style -thus achieving to build a kind of limbo between the living and the dead. There, the omnipresent tags cease to be mere vandalism to become a kind of spectral persistence, where every corner of Calgary seems to bring back the memory of the dead. The Maiden seems to drink as much from the rivers of Gus Van Sant’s deep Americana as from the magical neorealism of Alice Rohrwacher – even, perhaps, some of Lucrecia Martel’s work. Nostalgia has never been so palpable, and one of the main achievements is the way Foy makes those multiple slacker activities that in everyday life would seem to have no specific purpose become something magical, like the scene in which simple-minded jock displays, completely out of the blue, some unusual keyboard skills (one of the rarest and most beautiful moments in the festival). Among all these images, similar to the mystical ascent to the roof of Sons of Ramses, when the young griever skates down a steep slope, it seems that through these apparently reckless acts, he has opened a new portal, different from the world of loss and sadness. These magical and ritualistic moments, made with natural and everyday elements, are the most impressive images that the festival left us.

Agustin Acevedo Kanopa

© FIPRESCI 2022