Sitting down, standing up: on facing the ugliness

When jury president Patricia Mazuy took to the stage to announce the winners of the 29th Sofia International Film Festival, she spoke of a world that is “bad, violent and ugly.” Such was the backdrop to an International Competition that comprehensively surveyed the depths of a rotten socio-economic landscape across Europe, with a couple of notable incursions overseas for US productions.

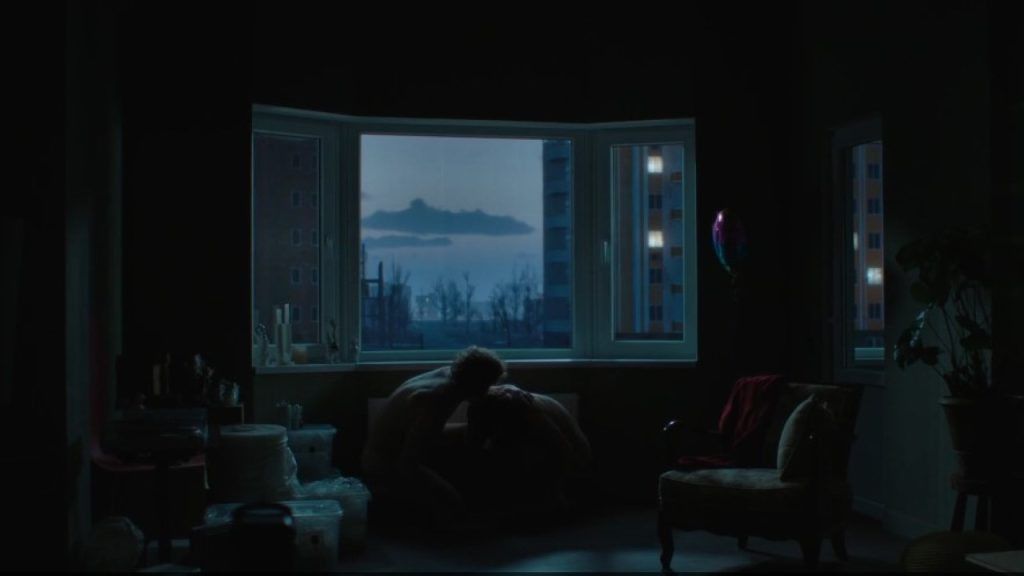

Of course, Mazuy’s statement referenced most directly the night’s big winner, which added a Young Jury Prize to its Best Film award. Zhanna Ozirna’s Honeymoon (Medovyi misiats) deals with the immediate aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, recounting the events following February 24th, 2022 – alarms, explosions, tanks in the street, and people fleeing their homes – by retreating deep into the nuclear, domestic realm of a couple hiding away in their apartment and evading the attention of invading enemy troops.

With what is in many ways the only viable setup for a low-budget film (made with the help of Venice’s Biennale College development program) that still wants tell fictional stories in a country at war, Honeymoon manages to shrewdly elevate its premise by turning the couple’s new beginning into a last stand. Having just moved into their apartment, they are surrounded by signifiers of a life not yet lived, marked by boxes and paint swatches, and with future furniture only existing in the form of a taped outline on the walls. The contrast with the unseen menace lurking outside is effective, and in the face of an all-too-real apocalypse the two characters begin to inhabit the space around them with a snail-like choreography and an intimate pacing performance.

Elsewhere, the danger posed to people’s homes was less urgent and lethal, and instead steeped in institutional decay. Sometimes quite overtly, as in the case of Polish entry Under the Grey Sky (Pod szarym niebem) and its fictional tribute to real Belarusian journalists persecuted by Lukashenko’s regime. While terse in style, the work of Polish-Belarusian director Mara Tamkovich exudes – just like her uncompromising protagonist – a quiet and straightforward determination to make its story known. And if tales of the country’s authoritarian crackdown on free press and targeting of private citizens are still somewhat under-reported across the continent, the Belarus-born director has to be lauded for her account of how dissent gets choked out by the state, one home at a time.

There’s an ideal link between that film, which features a lawyer backing down from her client’s defense in fear of governmental retaliation, and a scene from Croatia’s Hallway to Nowhere, in which a police officer admits to a girl in need of protection that the system is too corrupt and inefficient to help her – suggesting she shoots the unwanted tenant in her home instead. Zvonimir Munivrana’s dark twisting of the domestic thriller genre imagines the inside of yet another apartment as a contested frontier, surrounded by a moral wasteland and almost nihilistic levels of distrust in Croatia’s institutions, to a degree that makes it impossible not to think of the recent anti-corruption protests in neighboring Serbia.

Serbia itself was represented by Cat’s Cry (Mačji krik), a modest but touching drama once again pitting the individual against the state, this time through the lens of healthcare, in the shape of a newborn affected by a rare genetic syndrome. Only the girl’s grandfather Stamen (a towering performance from veteran Bosnian actor Jasmin Geljo) steps up to care for her amidst a toxic blend of small-town prejudices and bureaucratic challenges, which director Sanja Živković navigates earnestly. She took home the Special Jury Prize thanks to a few astute directorial touches and some genuine warmth in the treatment of her characters.

From a newborn to a deceased, and bringing it all back home to Bulgaria, it was Pavel G. Vesnakov’s sophomore feature Windless (Bezvetrie) that left a lasting impression with its arresting visual style and lived-in atmosphere. The last in a long list of characters sitting across a government official and pleading for assistance in what felt like a leitmotif of this SIFF 2025 International Competition, its protagonist Kaloyan (Ognyan Pavlov) has left the country for a life abroad but carries with him the kind of intergenerational pain that sticks to the skin like the ink of his extensive tattoos. His return to rural Bulgaria is of the archetypical variety, as he symbolically buries his father by practically dealing with paperwork and disposing of his material possessions, neither of which he holds a particular interest in. But being there, if you stick around for long enough, is a virtue of its own. And listening to echoes of a past life that now reverberate in others might yet move even the most indifferent among us.

By Tommaso Tocci

Edited by Savina Petkova

Copyright FIPRESCI