Berlinale Talents 2015 – Day 2

Ana Sturm, Nobody Wants The Night

– Artistically empty and stereotypical portrait of naive female explorer –

Ana Sturm, Sometimes Things Are just Bad

Heitor Augusto, Keeping It Simple

– Joaquim Pinto’s and Nuno Leonel’s documentary on artisanal fishing manages to be more than a pure registry –

Julia Cooper, Sex in Brooklyn: Joanna Arnow’s “Bad At Dancing”

Monty Majeed, Trying to Stay Afloat

Oriana Franceschi, A Tangled Web that Children Weave

Nobody Wants The Night

Artistically empty and stereotypical portrait of naive female explorer.

By Ana Sturm

A delicate, pale face, covered with strange futuristic glasses, is wedged in a pile of furry animal skins, a gramophone plays while a group of arctic explorers crosses the infinite white landscape on a dog sled. Mrs. Josephine Peary is a woman on a mission. Her mission is to follow her husband to where no one has ever set foot before – the geographical North Pole.

A delicate, pale face, covered with strange futuristic glasses, is wedged in a pile of furry animal skins, a gramophone plays while a group of arctic explorers crosses the infinite white landscape on a dog sled. Mrs. Josephine Peary is a woman on a mission. Her mission is to follow her husband to where no one has ever set foot before – the geographical North Pole.

“Nobody Wants The Night” (Nadie qiere la noche, Spain, France, Bulgaria, 2015) kicked off this year’s Berlinale Competition. The fact that it was made by an acclaimed female director, Isabel Coixet, and that it tells the story of two women who find themselves in the deadly embrace of one of the longest and coldest “nights” of their lives, made us expect a more modern female-driven piece than the one it actually delivered.

We could admire Josephine, for her courage, intensity and craziness are far greater than that of her male companions, but the film draws our attention to her beautifully designed dresses and her bourgeois manners — only serving the aesthetics of the film. In the end she becomes a tragic stereotype of naive female explorers, which is, sadly, far from who she was in real life.

The film also vaguely tries to explore some racial and humanistic matters. The two main characters, Mrs. Peary and Allaka, are strangers from two different cultures. But what does that really mean in the empty wastelands of the far north? There is no society, no rules and no judges. Only wide open spaces and the extreme cold. The only thing that matters is survival.

Life in the “winter desert” is stripped down to the basics. You have to eat and you have to stay warm. You have to stay alive. The pulse that sustains their lifeline comes from inside. Compassion slowly melts the thick ice-shield that surrounds the two of them. But what happens when only one of them can survive? Who can safely return home and who is sent into the night?

Ana Sturm

Sometimes Things Are just Bad

By Ana Sturm

A toxic film monster that shows us a slowly degrading relationship between two long-time friends.

A toxic film monster that shows us a slowly degrading relationship between two long-time friends.

If “Listen Up Philip” (USA 2014) was a dramatic comedy about two horrible men, the Berlinale Forum film “Queen Of Earth” (USA 2015) comes across as some scarily weird, but at the same time, extremely exciting hybrid between mumblecore, horror and psychological thriller, dealing with the trope of broken women. It’s a toxic film monster that shows us a slowly degrading relationship between two long-time friends.

Elisabeth Moss is brilliant as Catherine, a young woman, trying to cope with some very recent and abrupt changes in her life. Her inability to deal with the death of her father and a broken relationship with her boyfriend increases her depression. Catherine’s narcissistic sense of entitlement also brings about passive-aggressive behavior in her friend Virginia. Much of the film consists of long conversations between the two. Mean dialogues and extreme close-ups create a tense environment in which everybody (including viewers) feels nauseated.

The time-shifting narrative, which is brilliantly underlined by a very misleading score, creates the film’s increasingly unpleasant tone. Whenever we feel that we know what is going on, the music ads on another layer of meaning and completely changes our perspective of the story. We are constantly lost in the process of trying to understand what the hell is going on.

Even though the characters inhabit idyllic natural surroundings, they are suffocating under the weight of their own fear and anxieties. The fresher the air, the more the epidemic of depression spreads. When they are in the city and surrounded by the normalcy of other neurotics and misanthropes everything is fine, but when they leave the city, they face only nature and themselves, and slowly fall into madness.

Alex Ross Perry is quickly becoming one of the strongest voices of his generation. With “Queen Of Earth” he has established himself as a brilliantly uncompromising contemporary auteur. He doesn’t spare any of his miserable characters anything. He show us all of their faults, shortcomings and endless uncertainties. Because sometimes things are just bad.

Ana Sturm

Keeping It Simple

By Heitor Augusto

Joaquim Pinto’s and Nuno Leonel’s documentary on artisanal fishing manages to be more than a pure registry.

Joaquim Pinto’s and Nuno Leonel’s documentary on artisanal fishing manages to be more than a pure registry.

“Fish Tail” (Rabo de peixe, Portugal, Berlinale Forum) is a documentary about an artisanal fishing village in the Azores. We see the daily routine of the workers, try to understand their dialect, observe their faces, feel the threat of death from the sea, and share their dilemmas as a community and as individuals. What could have been just an ordinary documentary about a traditional form of fishing becomes instead, through Joaquim Pinto’s and Nuno Leonel’s powerful shots, a visual essay on honest friendship, and a poetic comment on redefining one’s identity while getting in touch with a new environment. This is a tender registry of a world whose very existence is nearing its end because of the impeding implementation of the Euro Zone.

Pinto’s and Leonel’s approach to their material is rooted in their fascination for a place that is different than the familiar context they knew on the continent. The voiceover shows us how moved they are by the village of Rabo de Peixe. One of the strengths of this film is that the filmmakers present banal events through an enchanted perspective that reflects their genuine interest in the characters’ lives.

Rui, a farmer who becomes a fisherman after marrying and joining his father-in-law’s business, does not know how to swim, which is an obvious necessity for a fisherman. After several failures in his attempts to learn, Rui finally manages to overcome his fear of water and swim a reasonable distance without drowning. The filmmakers capture Rui’s feelings through his face which turns this simple swim into an Ulysses-like journey, as if he had returned home after a long adventure like Homer’s hero.

This is a film that stays in our memory long after the screening is over. “Fish Tale” leaves us with a bitter-sweet taste. We a feel a sadness for the end of that world, but it is accompanied by a feeling of happiness for having been fortunate enough, through this documentary, to share in these people’s lives.

Heitor Augusto

Sex in Brooklyn: Joanna Arnow’s “Bad At Dancing”

By Julia Cooper

Does the world need another coming of age story? Maybe not, suggests Brooklyn filmmaker Joanna Arnow with her latest short film running in the Berlinale Shorts Programme, “Bad At Dancing”. Set mostly in a two-bedroom walkup in New York, Arnow’s film appears frustrated with the platitudes of self-discovery typical of the genre (another NYC film, “Frances Ha”, comes immediately to mind) though it does not discard its tropes altogether. Instead, Arnow plays the cliché of late-twenties ennui deadpan and presents the conventionally angsty love triangle as hilariously lopsided.

Does the world need another coming of age story? Maybe not, suggests Brooklyn filmmaker Joanna Arnow with her latest short film running in the Berlinale Shorts Programme, “Bad At Dancing”. Set mostly in a two-bedroom walkup in New York, Arnow’s film appears frustrated with the platitudes of self-discovery typical of the genre (another NYC film, “Frances Ha”, comes immediately to mind) though it does not discard its tropes altogether. Instead, Arnow plays the cliché of late-twenties ennui deadpan and presents the conventionally angsty love triangle as hilariously lopsided.

Drawing inspiration from her personal documentary “I Hate Myself :)”, Arnow performs a version of herself in “Bad At Dancing”. Dour and lacking all sense of boundaries, Joanna repeatedly walks into her roommate’s bedroom to talk about her problems while Isabel (Eleanore Pienta) is busy having sex with her boyfriend Matt (Keith Poulson). Captured in tight frames and shot in black and white, the friends’ conversations unfold as though Joanna’s “visits” are nothing more than mere annoyance. As such, the couple’s sex is immediately naturalized, recalling the mechanical moving bodies of Yorgos Lanthimos’ “Dogtooth” or Elizabeth Olsen’s detached voyeurism in “Martha Marcy May Marlene”. The comedy of these scenes is heightened by Joanna’s unwavering monotone and slightly slack-jawed expression. When Matt looks side-eyed at a fully clothed Joanna while Isabel thrusts atop him, he suggests to his girlfriend that her roommate ought to leave. Joanna inches her face closer and chastises: “It is rude to talk about someone in the third person when they are right next to you.”

Though the film’s dialogue is monotone and its visuals monochromatic, “Bad At Dancing” maintains a witty tempo, bolstered in part by its cheeky referentiality. In one instance, Joanna sits naked in shallow bathwater squabbling with Isabel and Matt in a scene that is an unmistakable visual reference to Lena Dunham (also playing a semi-autobiographical protagonist) in the pilot episode of Girls. Yet Arnow is not an aspirational filmmaker trying to re-plot the coordinate’s of Dunham’s Greenpoint. No, when Joanna finds pleasure it is by her own hand, making “Bad At Dancing” something awkwardly and wonderfully masturbatory.

Julia Cooper

Trying to Stay Afloat

By Monty Majeed

Where’s the fun in chasing a single ball along the ground? To ten-year-old Giovanni, football is boring. So is karate, unless “it involves murder”. Instead, Giovanni has his eyes on a spot in the synchronized swimming team, competing in the Dutch National Championship. Having harbored this dream for four years now, Giovanni is just one final test away from being certified. Astrid Bussink’s short documentary “Giovanni And The Water Ballet” (Netherlands, 2014), presented in the Berlinale Generation, follows the boy as he readies himself for the big test, just four weeks away as the movie begins.

Where’s the fun in chasing a single ball along the ground? To ten-year-old Giovanni, football is boring. So is karate, unless “it involves murder”. Instead, Giovanni has his eyes on a spot in the synchronized swimming team, competing in the Dutch National Championship. Having harbored this dream for four years now, Giovanni is just one final test away from being certified. Astrid Bussink’s short documentary “Giovanni And The Water Ballet” (Netherlands, 2014), presented in the Berlinale Generation, follows the boy as he readies himself for the big test, just four weeks away as the movie begins.

“You will make headlines,” Giovanni’s girlfriend Kim, with whom he is “going steady,” tells him excitedly. If he passes the test, Giovanni would become the first boy in his country to break into the competitive world of synchronized swimming, a sport dominated by girls. Unlike other boys his age, Giovanni gets along with his teammates and thinks that girls are fun—chasing one another under water. But Giovanni is still very much isolated in this world of glittery swimsuits, nose clips, and noisy giggles. Bussink captures this beautifully in a scene where Giovanni splits from his chattering teammates to go to the boys’ locker room to change after practice. He stands alone in the blue-tiled room, drying himself with a towel as his teammates’ voices ring loudly from the adjacent girls’ locker room.

Giovanni’s story unfolds breezily, interlaced with humor and accented by an energetic background score. Bussink hits the bulls eye by interspersing the tense pool practice sessions, in which Giovanni struggles to stay afloat, with scenes that capture the innocent banter between Giovanni and Kim, striking a fine balance in capturing the stress and relief in the boy’s life. Most of the film’s humor stems from conversations between Giovanni and the ever-supportive Kim, who together, contemplate the meaning of relationships, dreams, and life. Although Bussink never shows Giovanni’s parents, it’s mentioned that they’re okay with his quirky passion. Still, exploring that angle of Giovanni’s story would have helped tie up the film’s loose ends.

Thanks to the refreshing underwater sequences—tastefully shot by cinematographer Diderik Evers, a Berlinale Talents alumnus — the film has a polished look. Because of the choreographed swimming set pieces, and Bussnik’s energetic and novel use of music, the film might appear staged to some. But as Godard has said, all good documentaries tend toward fiction. In 17 minutes, “Giovanni And The Water Ballet” both entertains and encourages us to follow our dreams—even if we are the only ones chasing them.

Monty Majeed

A Tangled Web that Children Weave

by Oriana Franceschi

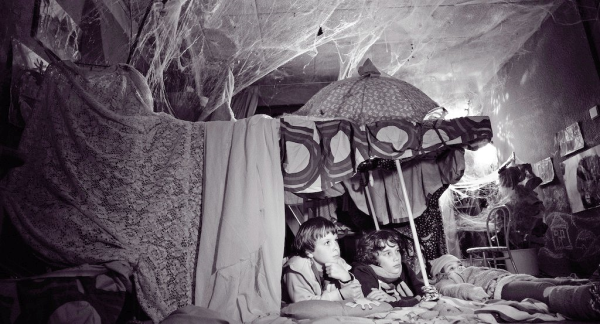

The children in “The Spiderwebhouse” (Im Spinnwebhaus, Germany) make their insect pets feel at home. They plant a stick in a saucepan of dirt and set little beetles free to roam around it, and open their dollhouse door to welcome bugs inside. The floor of their own house grows thick with leaves and a dense, webbed forest grows over the ceiling; impossibly, we can hear the tiny footsteps of spiders as they tiptoe around the house. “The Spiderwebhouse”, part of the Perspektive Deutsches Kino, is Mara Eibl-Eibesfeldt’s tale of three children, Jonas, Nick and Miechen, whose mentally ill mother leaves them so she can “fight her demons” in a mysterious land known as Sunvalley.

The children in “The Spiderwebhouse” (Im Spinnwebhaus, Germany) make their insect pets feel at home. They plant a stick in a saucepan of dirt and set little beetles free to roam around it, and open their dollhouse door to welcome bugs inside. The floor of their own house grows thick with leaves and a dense, webbed forest grows over the ceiling; impossibly, we can hear the tiny footsteps of spiders as they tiptoe around the house. “The Spiderwebhouse”, part of the Perspektive Deutsches Kino, is Mara Eibl-Eibesfeldt’s tale of three children, Jonas, Nick and Miechen, whose mentally ill mother leaves them so she can “fight her demons” in a mysterious land known as Sunvalley.

In this house, where the inside is full of outside, the child becomes the parent as Jonas (an angelic Ben Litwinschuh), determined not to let child services divide his family, cares for his siblings. Over time, hair becomes matted, jumpers are streaked with filth, and healthy young faces develop dark circles, bruises, and grimy shadows. Strange visitors begin to call at this spiderweb house: A pale old lady who calls herself Dracula, a rattling punk with a stray ladybird crawling up his neck, an unwelcome father under some spell that blinds him to anything he doesn’t want to see. They all ask the same thing: Where is your mother? In this topsy-turvy fairytale world, the wicked witch from whom Jonas must save his little sister and brother is a kind kindergarten teacher with too many questions.

Shot in eerie black and white, “The Spiderwebhouse” is reminiscent of Charles Laughton’s “Night Of The Hunter”, but lacks that film’s dark magic. Eible-Eibesfeldt teeters so temptingly on the brink of childish fantasy, that at times it feels, frustratingly, as though she’s holding something back. The film would have benefited from more near-magic moments, like the child-sized bicycles that appear from nowhere, and a night that turns to day in the blink of an eye.

“The Spiderwebhouse’s” strongest scenes are those that show the children interacting with one another; they’re funny and touching. In their wild living room, the children build themselves an indoor cave of blankets and live inside it like babes in the wood. Close and affectionate, they fall asleep with their arms around each other, lying on the back of a giant toy tiger. If we listen closely enough, we can hear it purring with love.

Oriana Franceschi