Second Day

The Shape of Our Inner Fears, by Elizabeth Chege

A Romanticized Attachment to Home, by Isabella Akinseye

Depicting the Refugee Crisis, by Rasha Hosny

Digging the Past, by Ruben Demasure

The (Alien) Children Are Watching Us, by Sergio Huidobro

Music as a Trope of Palestinian Landscape, by Sevara Pan

The Vibrant Bunker, by Xin Zhou

Casting Directors, Career-Makers, by Tara Karajica

We Are all Theatre, by Sevara Pan

A Raw Glimpse at the Morality of Crime, by Elizabeth Chege

The Shape of Our Inner Fears

By Elizabeth Chege

Structured in the style of a dream, “Der Nachtmahr” (in the Lola @ Berlinale section) centers on teenage girl, Tina (portrayed brilliantly by Carolyn Genzkow), who stumbles upon a strange and frightening creature after a drug-fueled late night rave. While initially it seems to be the outcome of her imagination, when the blind creature turns up in her home, we know it’s there to stay. This grotesque figure succeeds in terrifying her and the encounters morph into visceral, all-consuming experiences. To the detriment of Tina’s mental wellbeing, this apparition is only visible to her, which leads to fractures in her friendships and family relationships. With the threat of being placed in a mental hospital looming heavily, the only choice left is to find a way to deal with her new circumstances and protect her fragile psyche. After her psychiatrist surprisingly advises her to talk to the beast, challenges pile up when the creature refuses to obey. She soon realizes that she and her newly found companion are stuck together.

Structured in the style of a dream, “Der Nachtmahr” (in the Lola @ Berlinale section) centers on teenage girl, Tina (portrayed brilliantly by Carolyn Genzkow), who stumbles upon a strange and frightening creature after a drug-fueled late night rave. While initially it seems to be the outcome of her imagination, when the blind creature turns up in her home, we know it’s there to stay. This grotesque figure succeeds in terrifying her and the encounters morph into visceral, all-consuming experiences. To the detriment of Tina’s mental wellbeing, this apparition is only visible to her, which leads to fractures in her friendships and family relationships. With the threat of being placed in a mental hospital looming heavily, the only choice left is to find a way to deal with her new circumstances and protect her fragile psyche. After her psychiatrist surprisingly advises her to talk to the beast, challenges pile up when the creature refuses to obey. She soon realizes that she and her newly found companion are stuck together.

Artist and filmmaker Akiz aimed to portray the ogre as a manifestation of Tina’s fears. In a similar vein to Aronofsky’s “Requiem Of A Dream”, Akiz uses camera techniques, non-chronological editing and color to convey the inner unravelling of our protagonist. We are often told to “overcome” our fears, but an interesting idea posited by Akiz is that perhaps there is something to be said about feeding those fears instead. After growing accustomed to the presence of the creature, Tina starts to literally feed it, suggesting that she is on her way to mastering her own phobias.

While the director succeeds at presenting teenage angst realistically, “Der Nachtmahr” falls short of convincing us that the character’s journey evolves, even in light of what appears to be her final acceptance of the newfound state of affairs. The initial premise of a macabre psychological thriller is sidestepped when the director chooses to offset the story and moves in a disappointing direction in the final coda. Where the film truly triumphs is in its strong performances, stunning visual effects, non-linear structure and soundtrack whose dissonant score is in line with the film’s disorientating tone.

A Romanticized Attachment to Home

By Isabella Akinseye

The Berlinale Competition film “Letters From War” (Cartas da guerra, Portugal) is based on a book by renowned Portuguese author António Lobo Antunes. The film focuses on the letters that Antonio, a young army doctor, sent to his wife from Angola between 1971 and 1973 during the colonial war.

The Berlinale Competition film “Letters From War” (Cartas da guerra, Portugal) is based on a book by renowned Portuguese author António Lobo Antunes. The film focuses on the letters that Antonio, a young army doctor, sent to his wife from Angola between 1971 and 1973 during the colonial war.

Ivo Ferreira’s film is narrated chronologically, starting from Antonio’s first letter dated Jan 14th 1971, which he wrote when still on board the Vera Cruz sailing to Luanda, Angola. Antonio expresses sadness about leaving his pregnant wife behind in Portugal. This sets the tone for a series of letters he would write throughout the three-year period. His wife, who has very limited screen time, is heard reading each of his letters. We are only given glimpses of her responses or lack thereof through Antonio’s missives.

The director presents the Portuguese soldiers in a positive light; as victims fighting a ‘stupid war’ which they neither understand nor support. Paradoxically, the black soldiers are the ones killing their fellow black Angolans, a sight that Antonio cannot bear.

Despite his fascination towards African landscape and the warm reception he receives from the locals, Antonio does not fully blend in and remains faithful to his wife and country. While he becomes a godfather to one of the newborn babies and even temporarily takes in an orphaned child, his views on African traditions remain imperialistic. Witnessing a child marriage, Antonio expresses his disgust towards it in one of his letters. Yet he is powerless to do anything when a man says that he’d rather have his wife dying at home than having her moved to a nearby town for medical testing. “Only elephants go away to die,” he says.

While the film succeeds in presenting a romanticized version of his attachment to his homeland, one finds Antonio’s attitude inconsistent, vacillating between hope and despair without ever coming to his own. In what feels like an abrupt ending, he urges his family to join him in Angola in a last letter written against a picturesque rising sun.

Depicting the Refugee Crisis

By Rasha Hosny

“It is hard to film these crises in cold blood as if it is a calm and ordinary situation”, said German filmmaker Philip Scheffner, one of the participants in the “No Time to Remember: Films on the Move” panel, one of the Berlinale Talents 2016 events. Moderated by Rasha Salti, the discussion focused on the role of both narrative and documentary filmmakers in depicting the refugee crisis around the world.

“It is hard to film these crises in cold blood as if it is a calm and ordinary situation”, said German filmmaker Philip Scheffner, one of the participants in the “No Time to Remember: Films on the Move” panel, one of the Berlinale Talents 2016 events. Moderated by Rasha Salti, the discussion focused on the role of both narrative and documentary filmmakers in depicting the refugee crisis around the world.

Scheffner’s phrase reflects one point of view on these filmmakers: to refuse filming with sentimentality. On the other hand, he considered his films to be about looking and observing: “As a refugee, you look at certain points to find the horizon and say the future is over there on the other side. But it could be the border also.”

Avo Kapealian, the director of “Houses Without Doors”, filmed his documentary about the daily routine of his Armenian neighborhood in Syria from his balcony, showing how war affected people’s everyday activities. “When I was a child, there was a very big book in my house about what happened to the Armenians, it was full of pictures, and it made me wonder how somebody can capture these photos without thinking about doing something else at that very special moment. That leads me to think about documentaries and how they could be effective in such situations,” Kapealian said. The personal experience was Kapealian’s approach in making his documentary.

Most of the participants have experienced migration and displacement, such as Khalid Abdel Wahed, who was raised in Syria and went to the United States for one year. His short film “Slot In A Memory” is about two Palestinian and two Syrian children playing on a swing as bombs explode outside their refugee camp in Lebanon. The camp once only served Palestinians but now is also receiving refugees from Syria. “Children in this camp have a shared memory even in different political situations,” Khalid said, suggesting that politics leads history to repeat itself.

Digging the Past

By Ruben Demasure

“I’ve been picturing this place in my mind for years,” begins Burma-born and Taiwan-based filmmaker Midi Z in his documentary “City of Jade” (Fei cui zhi cheng, Taiwan/Myanmar). He’s talking about the jade mines in Myanmar’s war-torn Kachin state on the border with China. Because of the conflict, companies left the site to illegal treasure hunters, the filmmaker’s missing brother being one of them. He had been released for opium abuse, the family last heard. In the film, the director finds his sibling who left sixteen years ago on his gemstone exploits. Midi Z’s mission mirrors Robert De Niro’s attempt in “The Deer Hunter” (1979) to save a close one from drug-infused risk-taking in a Hanoi hellhole and bring him back home.

“I’ve been picturing this place in my mind for years,” begins Burma-born and Taiwan-based filmmaker Midi Z in his documentary “City of Jade” (Fei cui zhi cheng, Taiwan/Myanmar). He’s talking about the jade mines in Myanmar’s war-torn Kachin state on the border with China. Because of the conflict, companies left the site to illegal treasure hunters, the filmmaker’s missing brother being one of them. He had been released for opium abuse, the family last heard. In the film, the director finds his sibling who left sixteen years ago on his gemstone exploits. Midi Z’s mission mirrors Robert De Niro’s attempt in “The Deer Hunter” (1979) to save a close one from drug-infused risk-taking in a Hanoi hellhole and bring him back home.

The director’s quest to gain a picture of his brother and these mythical mines has taken different iterations. For his documentary debut “Jade Miners” (2015) he wasn’t allowed to travel to the region himself and so he made a compilation of footage that locals shot for him. At this year’s International Film Festival Rotterdam, he presented the project in an installation, “My Folks In Jade City” (2016). Right at the beginning of the “City Of Jade” shoot, the director’s camera equipment was confiscated by the Burmese army. Therefore, all the footage was shot in secret with consumer cameras.

The technical restrictions result in an arresting aesthetic with the mountain landscape drenched in a digitally noisy, saturated color palette. Matte-like gold and orange hues haunt the hills and contrast with the stark blue tarps on top of the miners’ shacks. It brings to mind Richard Mosse’s Venice Biennale installation, “The Enclave” (2013), in which the use of infrared stock turned his war imagery pink. Here, the colors cast the environment as an expressionist, surreal and psychedelic impression of his brother’s mental landscape. Just like the miners manically turn over a stone to check it for cracks from all sides, the brother doesn’t expose his core that easily.

The (Alien) Children Are Watching Us

By Sergio Huidobro

“Midnight Special”, Jeff Nichols fourth feature and his third premiere at the Berlinale, merges road movie formulas with a sci-fi plot.

“Midnight Special”, Jeff Nichols fourth feature and his third premiere at the Berlinale, merges road movie formulas with a sci-fi plot.

Regarding his previous features, it’s clear that Jeff Nichols has some respect for seventies and eighties Hollywood mainstream classics. It’s also clear that he’s not going after any proven formulas or nostalgic advantages. As Nichols’ “Mud” (USA, 2012) revealed a fortunate appropriation of coming of age narratives, his recent premiere in the Berlinale Competition, “Midnight Special”, takes a creative, personal twist on sci-fi thriller materials which recall Spielberg’s alien-themed films or an “X Files” episode.

Starring Nichols’ amulets Michael Shannon and Sam Shepard, along with Joel Edgerton, Kirsten Dunst and Adam Driver, “Midnight Special” follows a father (Shannon) and his sickly child (Jaeden Lieberher) as they are pursued by both a religious group and the federal government when they learn that the kid has special powers. Joined by the child’s mother (Dunst) and a deserter trooper (Edgerton), they are all on the run both to evade the NSA to make a foretold appointment so that the kid can go back “where-he-come-from”, which could mean either death or an alien abduction.

That’s only an example of how the film constantly deals with ambiguity and disseminated information. But ironically, it’s unclear if it even succeeds in doing it or not. Sometimes it does and sometimes hints are left strangely unsolved. Surely it takes too long to know what is really going on or who isn’t insane, since everyone seems to have deep religious, political, scientific or new-aged expectations entrusted in the boy’s unusual skills. Nevertheless, Nichols’ script is compelling when it comes to building suspense and mixing drama with thrilling action sequences.

Nichols’ screenplay may evoke references such as “The Twilight Zone”, but “Midgnight” still feels like a pure Nichols film. It has the same ethical ambiguity as seen in “Mud” and that mood of menace upon an average American family that made “Shelter” work so well, and with Shannon playing a similar role here. Does that make Nichols an auteur? Maybe it doesn’t. But it makes him a filmmaker that’s worth watching.

Music as a Trope of Palestinian Landscape

By Sevara Pan

“A Magical Substance Flows Into Me” (Palestinian Territories), showing in the Berlinale Forum, opens with a crackly recording of the voice of Robert Lachmann, the Jewish-German ethnomusicologist who emigrated to Palestine in the 1930s and initiated a radio programme to explore the musical traditions of the various ethnic groups of Palestine. Inspired by Lachmann’s radio programme, Palestinian artist Jumana Manna sets out in search of the musical diversity in Israel and the Palestinian territories. Manna follows in the footsteps of Lachmann but instead of inviting the musicians to the studio, she visits them in their homes and places of worship.

“A Magical Substance Flows Into Me” (Palestinian Territories), showing in the Berlinale Forum, opens with a crackly recording of the voice of Robert Lachmann, the Jewish-German ethnomusicologist who emigrated to Palestine in the 1930s and initiated a radio programme to explore the musical traditions of the various ethnic groups of Palestine. Inspired by Lachmann’s radio programme, Palestinian artist Jumana Manna sets out in search of the musical diversity in Israel and the Palestinian territories. Manna follows in the footsteps of Lachmann but instead of inviting the musicians to the studio, she visits them in their homes and places of worship.

The film achieves an incredible degree of intimacy by engaging with the musicians within their own homes, in their living room, places of work, and often in their kitchen where warm yet difficult conversations transpire. Here politics are inextricable from music and life, present while they prepare dishes or make traditional coffee. Through the kitchen window, we look onto a conversation of an Israeli family talking about their Iraqi friend Yitzhak who sings the songs of Umm Kulthum to remain optimistic through his political exile. Music not only aids the narrative but propels it. What do songs sound like when performed by the Kurdish, Moroccan, Samaritans or Bedouins in today’s Israel and Palestine? Apart from revisiting the songs, the film returns to the musical history of the local ethnic groups of Palestine. Once immersed in the soundscape of the Palestinian vernacular music, I found the instructive voice-overs of the history lessons at times jarring me out of the cinematic experience. Although these lessons were insightful, staying within the moment of them singing or playing the rababa and saz would have created a more lasting impression of the music.

The Vibrant Bunker

By Xin Zhou

Colombia-raised and New York-based artist Mike Crane traveled to Lithuania and found a training camp that unemployed teenagers are sent to at the expenses of the European Union. The purpose of these camps is to recreate the socialist way of life in order to remind the younger generation of the benefits of the free market.

Colombia-raised and New York-based artist Mike Crane traveled to Lithuania and found a training camp that unemployed teenagers are sent to at the expenses of the European Union. The purpose of these camps is to recreate the socialist way of life in order to remind the younger generation of the benefits of the free market.

We sat down to discuss the artist’s unexpected discovery, the choice of the image in the video, and the difference between re-enactment and re-staging. Crane’s films “Bunker Drama” premiered in Berlinale Forum Expanded.

What was the history of the bunker that you shot this piece in?

It was an audiovisual archive that stored 16mm newsreels. The idea is that if the Soviet Union was destabilized by nuclear war, they would broadcast all of the films in the bunker, which contained every newsreel that the Soviet Union ever produced. It was never used, because nuclear war never broke out. Essentially, it’s a site outside of the Soviet Union that was intended to be the go-to place, to continue to broadcast and to make it look like the Soviet Union is doing fine.

Could you talk about the resolution of the film? Why did you intend to make it low-definition?

I chose to work with a camera that has a super 16mm sensor that simulates the look of a super 16mm film. It’s a little Black Magic Pocket cinema camera, small, and light-weight. I was interested in using a camera that simulates the way that those 16mm newsreels simulated the era. The intentional use of artifice, simulation, and staging is what the work really focuses on.

Can you talk more about the context of these military drillings that the teenagers undergo in the bunker?

January 2016 was the 25th anniversary of the independence from Soviet rule in Lithuania. It was also the 25th anniversary of the US bombing of Baghdad, which initiated the first Gulf War. Both of these events are being replayed today. The ongoing war in Iraq led to the US extraordinary rendition program using foreign black sites for torturing suspected terrorists, which we’re now learning Lithuania played a role in, and the rising fears of a Russian takeover of the Baltic states in light of the recent events in the Ukraine. Many of the fears expressed by the Soviet General’s impersonator in the camp touched upon the repercussions of these two contemporary scenarios.

Casting Directors, Career-Makers

By Tara Karajica

Tara Karajica talked to Prague-based US casting director Nancy Bishop (“The November Man”, “Mission Impossible 4”) about the importance of a casting director, the difference between the casting process in Europe and Hollywood and between casting stars and younger actors at the beginning of their career.

Tara Karajica talked to Prague-based US casting director Nancy Bishop (“The November Man”, “Mission Impossible 4”) about the importance of a casting director, the difference between the casting process in Europe and Hollywood and between casting stars and younger actors at the beginning of their career.

Tell us about the importance of casting directors and what made you become one?

Well, it happened by accident for me. I was a theater director and I was in Prague at a time when there were many film productions coming to shoot there. And so, I knew the talent and I knew the talents who were working so they would come to me. I had skills with actors, I could direct, I could get a performance out of them. So, that’s how my career started. It wasn’t really intentional. Casting directors assemble the talent, work as part of the production team and we create a palette of faces and talent that get together, that synergize, that have chemistry…

What is the difference between the casting process in Europe and in Hollywood?

Well, I would say it’s similar. And, you know, if you have a big budget film, I think it’s the same in Europe as it is in America, which is that you need some kind of big name talent to get the budget going. I think one difference is that in Europe, small countries have a film commission which finances films, and if it is already financed then you don’t have to worry so much about having a big talent for the green light. But in America, you’ve got the studios that finance the films but then, independent filmmakers have to raise the money themselves. There is no American film commission that gets them the money and they can’t apply for grants.

What is the difference between casting a star and actors like shooting stars or the Berlinale Talents actors?

The ones who are less known have to read for it. They have to go through the audition process. We give them part of the script and we work with them. And then, of course, with big stars, we just offer the part to them.

Do you love your job?

Sure! Yeah!

We Are all Theatre

By Sevara Pan

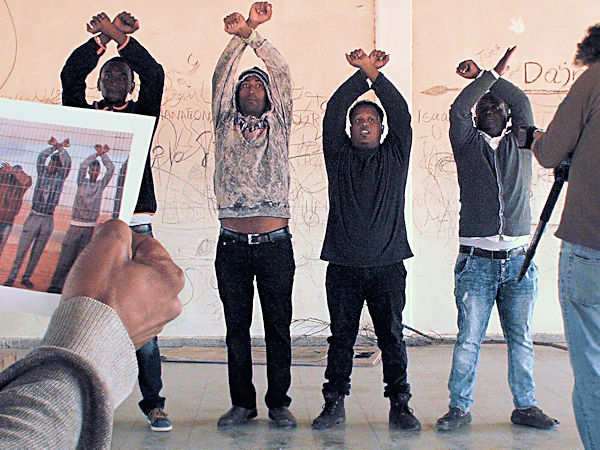

Following the principles of Augusto Boal’s “Theatre of the Oppressed,” “Between Fences” (Israel/France, Berlinale Forum), directed by the great Israeli auteur Avi Mograbi and theater facilitator Chen Alon, aims to bring about legislative change and social justice through art. The director engages both African asylum-seekers and Israeli citizens in a dialogue and critical reflection on the refugee crisis by introducing them to theatre. The film documents workshops in the Holot detention centre near the Egyptian border which houses thousands of rejected asylum-seekers whom the state of Israel officially designates as dangerous infiltrators but is unable to deport due to the country’s policies. Asylum-seekers from Eritrea and Sudan stage scenes from their own lives – roleplaying the drama of those who decide to stay and those who decide to leave. By filming theatre acts in an empty hall or wardroom, the director draws our attention to the African asylum-seekers turned actors, who are often mere “shadows on the streets of Israel” as Mograbi himself pointed out during the Q&A.

Following the principles of Augusto Boal’s “Theatre of the Oppressed,” “Between Fences” (Israel/France, Berlinale Forum), directed by the great Israeli auteur Avi Mograbi and theater facilitator Chen Alon, aims to bring about legislative change and social justice through art. The director engages both African asylum-seekers and Israeli citizens in a dialogue and critical reflection on the refugee crisis by introducing them to theatre. The film documents workshops in the Holot detention centre near the Egyptian border which houses thousands of rejected asylum-seekers whom the state of Israel officially designates as dangerous infiltrators but is unable to deport due to the country’s policies. Asylum-seekers from Eritrea and Sudan stage scenes from their own lives – roleplaying the drama of those who decide to stay and those who decide to leave. By filming theatre acts in an empty hall or wardroom, the director draws our attention to the African asylum-seekers turned actors, who are often mere “shadows on the streets of Israel” as Mograbi himself pointed out during the Q&A.

The use of ordinary objects such as chairs or kerchiefs denies us the opportunity to deflect from the raw emotion of drama which feels far too real to be fictional. In some scenes, actors are seen sculpting their own bodies into static images that depict their internal feelings of forced migration and discrimination. While the notion of theatre in prison has been explored in earlier documentaries from the Middle East (e.g. Zeina Daccache’s “12 Angry Lebanese!), Mograbi’s “Between Fences” not only erodes the stigma associated with prisoners but also dramatically reverses established roles, thus negotiating the concept of the Other in society. As the theatre workshop unfolds, Mograbi makes a daring move by involving Israeli men and women in the theatre troupe and assigning them the role of African refugees who are trying to cross the Israeli border. “This is not very real,” one of the African actors says. “Well, the words are real, but the colour is not,” he adds. “Between Fences” is a compelling and poignant film that shows how the temporary identification with the oppressed fosters a more profound understanding of what it means to be free in a society that detains those seeking protection.

A Raw Glimpse at the Morality of Crime

By Elizabeth Chege

A stolen car is methodically peeled of its previous owner’s belongings in a beautifully choreographed, devastating sequence – a stunning visual metaphor of the unfeeling crime world which our two protagonists inhabit. Russell (Legend’s Charley Palmer Rothwell) and Waylen (This Is England’s Thomas Turgoose) are car thieves. JACKED, a narrative short by Rene Pannevis running in Berlinale Generation, creates a stunning miniature portrait of two characters forced to a moral crossroads when they discover an item in the car that reveals more about its owner than they cared to know. A slice of their day is then spent in the grip of their indecision about what to do next.

A stolen car is methodically peeled of its previous owner’s belongings in a beautifully choreographed, devastating sequence – a stunning visual metaphor of the unfeeling crime world which our two protagonists inhabit. Russell (Legend’s Charley Palmer Rothwell) and Waylen (This Is England’s Thomas Turgoose) are car thieves. JACKED, a narrative short by Rene Pannevis running in Berlinale Generation, creates a stunning miniature portrait of two characters forced to a moral crossroads when they discover an item in the car that reveals more about its owner than they cared to know. A slice of their day is then spent in the grip of their indecision about what to do next.

Close-ups of Russell’s hands suggest a hardened life of physical altercations and sustained reckless behavior. At one point, he even set fire to the palm of his hand for a bet. Pannevis says that this was an aspect he elaborated during his research for the character. He even went to the gym to learn how to box in an effort to portray the character accurately. Coincidently, Rothwell’s own father used to be a boxer – a fact that was unknown to Pannevis until filming begun. Fatherhood is a motif reiterated throughout the film and is subtly introduced in a discussion about music between the two characters. The presence of a Lionel Richie album in a scene triggers a humorous conversation hinting that the characters, Russell in particular, don’t believe that sensitivity in a man is desirable. The mood changes when Waylen discovers a box of old audio cassette tapes of oral letters by a dying man and sets the two characters’ friendships on a course of conflict. While Waylen immediately recognizes their value and is desperate to return the car, Russell while affected, is ambivalent and unsentimental.

Pannevis is attracted to stories about young people in the criminal world having to make moral decisions, saying that he sometimes feels philosophical about it since he views it as a largely understated theme, “in most films dealing with these (decisions)… there are usually people who are smarter or older”. Rothwell agrees, adding that it’s a big moment when you become aware that what you are doing is wrong.” Pannevis adds that it was a life-changing moment in his own life when he chose to leave friendships with troubled friends behind.