A Tale of Two Mexican Cinemas

By Sergio Huidobro

In last year’s Berlinale Competition film “Eisenstein In Guanajuato” (UK, Mexico, 2016), director Peter Greenaway recalls the ten day visit that Soviet film pioneer Sergei Eisenstein made through the Mexican countryside in 1933. Greenaway attempts to achieve the same goal that led Eisenstein into frustration: to direct the ultimate cinematic experience of Mexican visual culture. Eisenstein’s !Que Viva Mexico! (URSS, Mexico, 1933) didn’t come out of the editing room until 1979, almost a half-century after it was shot and some thirty years after Eisenstein passed away. He died before he was satisfied with the film, as Greenaway points, for Eisenstein as an artist, Mexico held an everlasting but elusive promise.

In last year’s Berlinale Competition film “Eisenstein In Guanajuato” (UK, Mexico, 2016), director Peter Greenaway recalls the ten day visit that Soviet film pioneer Sergei Eisenstein made through the Mexican countryside in 1933. Greenaway attempts to achieve the same goal that led Eisenstein into frustration: to direct the ultimate cinematic experience of Mexican visual culture. Eisenstein’s !Que Viva Mexico! (URSS, Mexico, 1933) didn’t come out of the editing room until 1979, almost a half-century after it was shot and some thirty years after Eisenstein passed away. He died before he was satisfied with the film, as Greenaway points, for Eisenstein as an artist, Mexico held an everlasting but elusive promise.

There’s a gap between the real Mexico and the country depicted in films. Each movie that tries to bridge that divide becomes a fascinating measure of the distance between the two. Greenaway and Eisenstein’s endeavors to deliver a sincere vision of Mexico can be added to a long list that includes artists such as Breton, Picasso and Carrington, but also pop entertainment like the James Bond movie “Spectre” (UK, 2015), whose view on Mexican folklore seems as unnatural as Greenaway’s hyper-stylized mise-en-scène. Time and again, on the big screen, Mexico is more easily reduced to familiar iconography rather than drawn from reality.

Luis Buñuel’s “Los olvidados” (Mexico, 1950) could be proof or an exception to this assertion. A critical and commercial failure during its first theatrical run, its success at the Cannes Film Festival (and championed by Mexican poet Octavio Paz and surrealist artists) created a reputation back home. However, mainstream Mexican film industry-types expressed indignation towards the Spanish director’s depiction of impoverished outskirts and doomed childhoods. “That’s not Mexico,” box-office star Jorge Negrete said to Buñuel. But it certainly was.

Recent films awarded in Berlin, like successive First Feature Award winners “Güeros” (Mexico, 2014) and “600 Miles” (Mexico, US, 2015) went through a contemporary version of the same gauntlet: a paradoxical mix of critical approval and domestic viewers’ dislike. Their disappointing results are not a question of lack of industry support: they were widely released by local major distributors. It isn’t a lack of a domestic audience either: last year, Mexico ranked the tenth biggest box-office market worldwide. Nor is it matter of contempt regarding domestic talents: Mexican-directed productions gained almost $800 million US last year, including smash hits such as Guillermo del Toro’s “Crimson Peak” (US, UK, 2015) and Alejandro Iñárritu’s “Birdman” (US, 2015). Still, for some reason Mexican viewers remain unresponsive to arthouse cinema that tries to do more than provide diversion. Sixty years later, the “That’s not Mexico” reproach has evolved into another sort of self-denial: “That’s not what I paid for at the box office.”

Still, these artistically challenging, yet domestically challenged productions continue to be made. Three films that premiered in this year’s Berlinale explore social and violence-drowned contexts seen through unusual cinematic perspectives. Joaquin del Paso’s fiction feature, “Maquinaria Panamericana” (Mexico, 2016) and Tatiana Huezo’s documentary “Tempestad” (Mexico, 2016) were both screened in the Forum section, while Rafi Pitts’ fifth feature film, “Soy Nero” (Germany, France, Iran, Mexico, 2016) was included in Competition.

Given that these films have an unlikely chance for having a domestic audience that could justify their funding, it’s worth asking what sort of audience would embrace these films abroad, in the festival circuit, and for what reasons. In a recent article, Spanish film programmer Gonzalo de Pedro Amatria recalled what scholar Michael Zryd referred to as the fantasy of making the world better by watching films about social issues: poverty, war, migration.

That’s an old discussion related to cinemas of developing countries. It’s what Colombian filmmakers Carlos Mayolo and Luis Ospina used to call “misery porn” back in the seventies: that hunger of A-class film festivals for films starring beggarly children, demonic dictators or deathly guerrillas. Even nowadays, as Argentinean film critic Agustín Mango recently pointed out in a Hollywood Reporter piece, Latin-American filmmakers are thriving on and being awarded by the festival circuit, but their projects remain no match for the multiplex nor for local audiences.

Mexican cinema is certainly no exception to this tendency. The three aforementioned films that recently premiered in the Berlinale deal with some of Mexico’s prevailing issues: an unstable economy, cartel wars, immigration, human trafficking and corruption. Regarding these films, the task of film criticism is to determine whether each is bringing a renewed critical perspective about these topics, or simply reproducing the usual third world “misery porn” schemes.

Joaquin del Paso’s first feature “Panamerican Machinery” metaphorically deals with bankruptcy, populism and patriarchal economies through the story of a group of workers getting suddenly and frantically organized once they find the president of the company (a broken machinery import business) died in his office over night. The plot can be read as a critical portrait of societies that can’t discern between economic crashes and the night-before-the-dawn promises of upcoming prosperity. It’s also a tale about the fall of organized unions within neoliberal environments. The debauched company workers’ are blind to the reality, the game was, in fact, over a long time ago.

Tatiana Huezo’s documentary “Tempestad” is at once a social denunciation and a fresh take on the road film. It follows two Mexican women as they cross the country back home after being released from jail following an illegal arrest. Unlike del Paso’s concern with economic issues, Huezo focuses on a failed justice system that punishes people whether they’re guilty or not. The fact that the main characters are both women underlines a gender perspective. Just as Huezo’s first feature, “The Tiniest Place” (El lugar más pequeño, Mexico, El Salvador, 2011), “Tempestad” focuses on intimate stories rather than exhibiting obscene institutional structures.

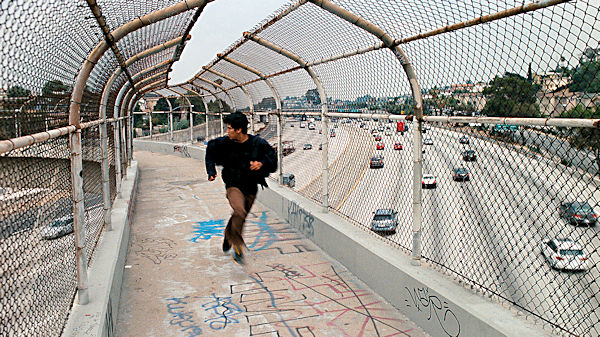

Lastly, Raffi Pitts’ “Soy Nero” (Mexico, Germany, US, 2016) deals with Hispanic immigration. The title character is determined to meet his elder brother somewhere in Los Angeles and then become enlisted in the U.S. army so that he can obtain a Green Card and American citizenship. A couple of fate twists, misunderstandings and luck both good and bad, lead him to the Middle East, only for him to find himself as un-American as he was in the beginning. “Soy Nero” is the first film Pitts shot outside Iran, but he shows a native understanding in depicting daily life on the southern border of the United States. Despite the fact that the film is dedicated to those immigrants deported after having served in the army, Pitts chose to appeal to the universal meaning of being an outsider instead of making a political statement.

Maybe the main value of these films is their sincere effort to point out the space between the real Mexico and the cinematic one. The yet unsolved question is whether they can appeal to Mexican viewers or die on the vine of festival press screenings. Regarding the domestic box-office triumph of “The Revenant” (US, 2015), it may be a good time to ask ourselves: what are Mexicans really talking about when they talk about Mexican cinema? For some, it could be a matter of prizes or international recognition. But maybe we’re talking about a deeper subject: the inner fear of sitting alone in the dark and being mirrored on the silver screen.