The Berlinale at a Distance

In the run up to this year’s Berlinale there was much doubt about the festival’s decision to take place as an in-person event: Could the festival really go ahead in times of curfews, strict hygiene measures and the lack of international guests due to ongoing travel restrictions? Would attempting to pull-off such a festival be irresponsible? What if the Berlinale turned into a superspreading event during its ten-day run? Would the festival’s reputation be at stake?

“We believe,” explained the artistic director Carlo Chatrian, “that flexibility must now be replaced by firmness in the context of a project that can no longer forsake its primary role. This is based on the certainty that a festival like the Berlinale can only exist under specific conditions. This is not about imposing one modus operandi (in-person) in opposition to another (online), but rather about acting as the guardian of a space that is at risk of disappearing. Seeing a film in a theatre, being able to hear breathing, laughter or whispers next to you (even with correct social distancing), contributes in a vital way not only to the viewing pleasure, but also to strengthening the social function that cinema has, and must continue to have. If films claim and aspire to depict human beings and the world in which they live, they must address a community, an audience, and not a collection of users each with their own login.”

The promise has worked out. The 72nd Berlinale took place as planned from 10th to 20th February. There was criticism on the festival’s decision to allow audiences at screenings around Potsdamer Platz, a large square in the heat of Berlin, and at the festival’s official premiere venue, the Berlinale Palast. So far, however, it seems that these events did not cause large scale spreading of the virus. During the festivals, 256 Films were shown and an impressive number of tickets sold, the hygiene regulations were strict and elaborate admission controls were perceived as “typically German”. Despite a few technical glitches, the films started on time. At this point. it seems none of the doubts and fears were justified.

Nevertheless, the Berlinale was very much dominated by the virus and the usual festival excitement could hardly be felt. Due to the routines of masks wearing, daily testing and an overall reserved mood, the atmosphere had something inevitably padded and sterile. It was a Berlinale at a social distance.

On the other hand, rarely in the past has the festival gone as smoothly as this 72nd edition. Outside, in front of the cinemas, small groups of people gathered to discuss the films they had just seen. They met and talked. That was a special phenomenon this year. Normally, everyone, especially journalists, rush past each other, wrapped up in thick winter coats. The Berlinale takes place in the Berlin winter, so woolen hats, scarves and several layers of clothing are mandatory before you leave the house. And this year? There were no long queues in front of the cinemas, no crowds trying to get hold of the best seat in the auditorium. The ticket system was based on confirmed seat numbers, and the thick winter coats lied comfortably in the neighboring seat. Because only every second seat in the cinema was occupied, there was plenty of space to indulge in the movie pleasure. The seat in front also remained free, so one had a good view of the subtitles (this year, even many of the German films had additional subtitles). The mood of the audience was quite laidback.

In fact, the Berlinale has never been so relaxed, which is certainly a win. And yet, the heat of excitement was lacking. In the evenings, the Potsdamer Platz was only sparsely visited and the city was less involved due to the lack of parties, a buzzing film market and the young Berlinale Talents party people. Big stars on the red carpet were also hard to find. The tribute to Isabelle Huppert had to take place without the guest of honour herself. Madame Huppert caught the virus a day before the ceremony and could not be present, like so many who were banned from participating in the festival due to its strict Covid regulations. Furthermore, the program was also greatly reduced in all sections although, according to the press conference, the number of film submissions this year was particularly high.

Films related to dealing with the global pandemic were available in all sections. However, in the films in this year’s competition, most directors kept their distance to Covid-19 and showed no traces of the pandemic in their stories. With two exceptions: Both Sides of the Blade (2022) by French filmmaker Claire Denis, who competed for a Golden Bear for the first time, and The Novelist’s Film by South Korean director Hong Sangsoo were the only films that showed their main actors appearing with masks in front of the camera without taking the matter further. The virus only accompanied these two very different stories in the background.

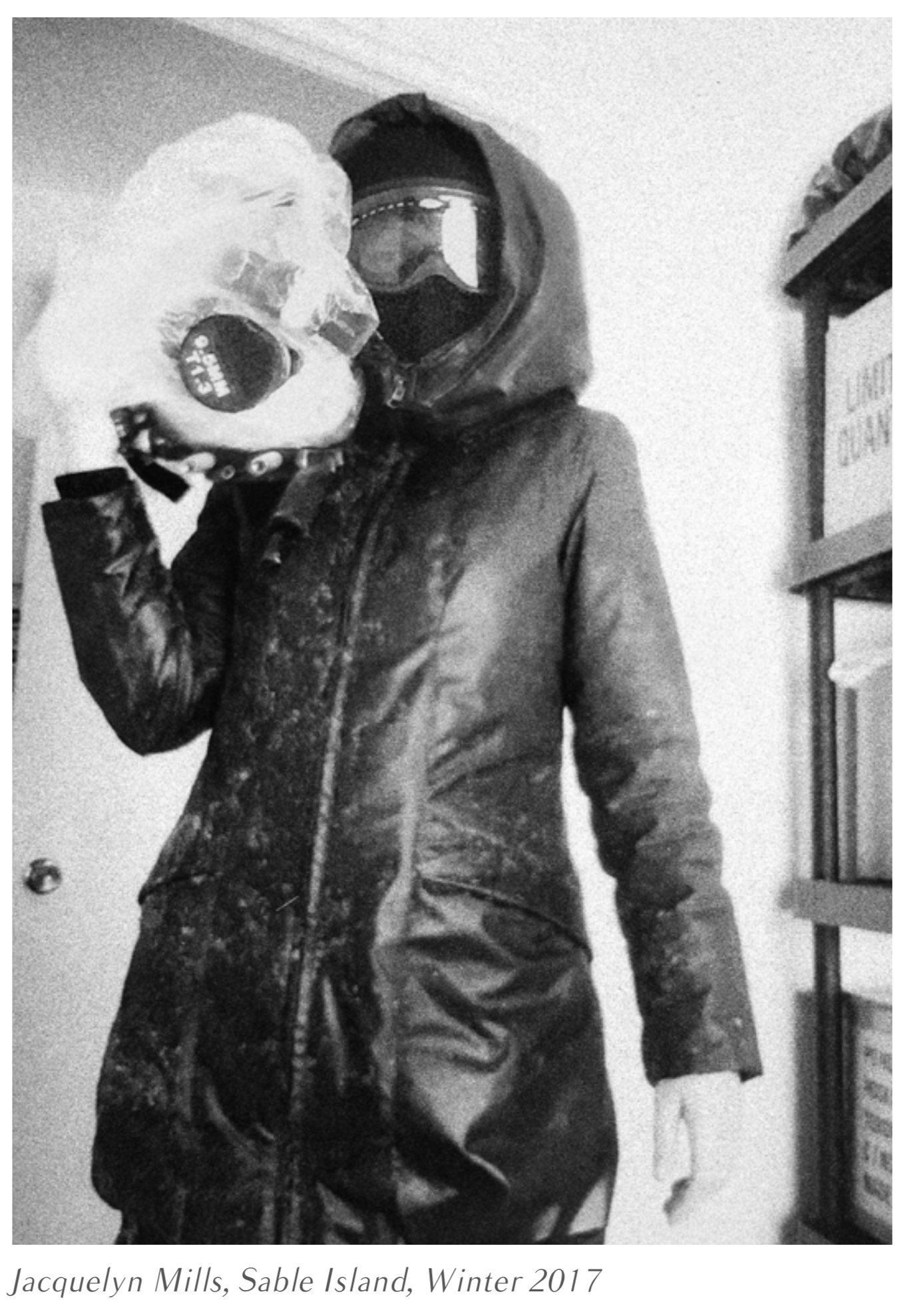

Instead, there were many films about solitude and isolation. This shows the real effects of the pandemic on our lives and our psyche after two years of fighting the disease. Dealing with loneliness or, in this case, a self-imposed solitude long before Covid was the theme of a film that stood out in the program and made viewers think: Geographies of Solitude (2022) by Jacquelyn Mills, which was shown in the Forum section, centred around questions about the self: What if I had found a basic topic in my life that would give me spiritual independence and a life task that fulfills me, come what may? Would this make me feel more secure in life?

Mills, an experimental filmmaker from Canada, travelled to Sable Island, a thin strip of land in the Atlantic, to accompany the Conservationist Zoe Lucas at work. Lucas has been cataloguing the island’s flora and fauna for decades, being the only permanent inhabitant of the island. She was an art student when she went there for the first time in the 1970s and has been living on this remote strip of land for decades now, mostly alone. Mills filmed Lucas on her daily trips around the island. Her studies of Sable Island’s population of wild horses, for which the island is famous, and of the general biodiversity have made the self-taught scientist an esteemed expert. Collecting the alarming amounts of plastic washing up also forms part of Lucas’s everyday life. Mills filmed on 16 mm, which lends a special beauty to the barren landscape. Science and art merge in the two women’s activities, each enriching the other. When Mills loads the final film reel into her camera, it is not just the shoot that is coming to an end, but also a special encounter between two people. Solitude takes on a new meaning in this film.

Was the decision right to let the Berlinale at Potsdamer Platz take place during the largest wave of Covid-19 in Germany since the start of the pandemic? Yes, it was. The strict safety measures and a fine selection of films made it possible. It was worth the risk. Mariette Rissenbeek, Executive Director, and Carlo Chatrian, Artistic Director, have shown courage and resilience. Now, we must withstand the current crisis of cinemas to make all the fantastic films in the programme accessible to a large audience. Watching films in the cinema is an elixir of life. This year’s Berlinale at a social distance was the proof.

Bettina Hirsch

Edited by Pamela Jahn

© FIPRESCI 2022