Essay Petra Meterc

All Your Corpses Now Begin To Speak – Through Film

By Petra Meterc

“But all our phrasing – race relations, racial chasm, racial justice, racial profiling, white privilege, even white supremacy – serves to obscure that racism is a visceral experience, that it dislodges brains, blocks airways, rips muscle, extracts organs, cracks bones, breaks teeth.” (Ta-Nehisi Coates, “Between the World and Me”)

“But all our phrasing – race relations, racial chasm, racial justice, racial profiling, white privilege, even white supremacy – serves to obscure that racism is a visceral experience, that it dislodges brains, blocks airways, rips muscle, extracts organs, cracks bones, breaks teeth.” (Ta-Nehisi Coates, “Between the World and Me”)

While the past year brought about several fiction films that dissected race relations and what it means to be black in America, three documentaries in this year’s Berlinale not only deal with racial issues, but address violence as the worst consequence of racism. Yance Ford’s STRONG ISLAND (2017, USA), Raoul Peck’s I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO (2017, USA), and FOR AHKEEM (2017, USA) by Jeremy S. Levine and Landon Van Soest try to understand violence as well as rewrite its narrative. The message that surfaces from all three films is that violence against blacks has not decreased from the days of the civil rights movement, and it does not seem to be getting any better.

STRONG ISLAND wouldn’t have been made if it wasn’t for a personal instance of violence – the director’s brother William Ford was a victim of a homicide in 1992. He was shot from afar, yet the official court decision proclaimed he was shot in self-defense, which led Ford to ask himself what the relationship between distance and fear is, and how the legal system measures that, since it seems that in the US, any kind of fear can legitimize such violence.

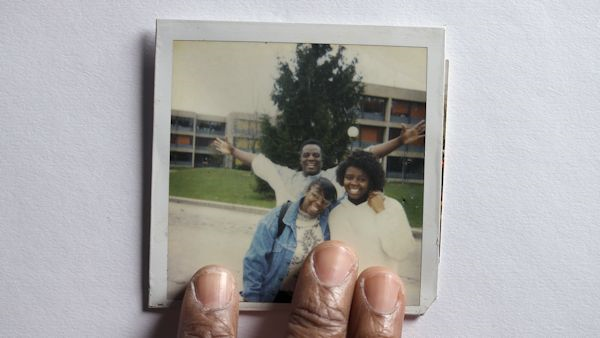

The film is a mixture of remembering and retelling of this tragic event, investigating the details of the case, but also dealing with the consequences this event had on his family. With a strong participatory tone, the film has a specific and thoughtful structure which includes “chair shot” interviews with his closest family members, displaying photographs of William and his family, Ford’s voiceover, and his frontal close-ups sharing his intimate views and emotions with the viewers.

Ford takes this act of violence and tells another version of the narrative, because as he says in the film, he is not only angry, but is also not willing to accept that someone else would define who William was. Ford regains agency and authority over the narrative by re-appropriating the media portrayal, and discounts the court’s version of this story. He does this by bringing forward the account of William Ford’s friend who was with his brother during the murder, as well as by repeatedly emphasizing the paradox of his parents moving to a Long Island suburb so that their children could live in a safer community.

The director intimately portrayed the violence that was inflicted on his brother and the personal impact it had on his family. Politically, the film reveals a harrowing account of the collective trauma and the aftermath of violence that has affected so many black families in the USA for the last 400 years. By exposing his family’s story on the screen, Yance Ford’s work is not only strong, but also extremely courageous. At the post-screening Q&A Ford also stressed that the risk of telling the story for him almost equals the risk of not telling the story at all.

In I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO, James Baldwin, the subject of the film, states that to forget the history of violence is to literally become criminals ourselves. Peck’s documentary is a mix-tape of clips from Baldwin’s lectures and interviews, of footage of the political happenings during the civil rights era and today, as well as of poignant clips from Hollywood movies that Baldwin refers to in his essay “The Devil Finds Work” (1976). The visual material is paired with a narration by Samuel L. Jackson who reads parts of Baldwin’s texts, most notably an unfinished work called “Remember This House”, in which he tells the story of America through the eyes of three of his friends, all involved in the civil rights movement, and all killed because of their activism: Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and Medgar Evers.

It appears that Peck conceives of Baldwin as the co-author of the film. In “The Devil Finds Work” Baldwin reflects that “stories are designed to reinsure that no crime was committed”. Peck shows clips from THE DIFFERENT ONES (1958, Kramer) which illustrate Baldwin’s point about the nature of racial hatred stemming from fear of blacks as a violent threat. This is also illustrated in Griffith’s THE BIRTH OF A NATION (1915), where the black man is not only docile and repressed, but is presented as a potential rapist. Peck juxtaposes Baldwin’s thoughts on violence towards blacks with scenes from Hollywood films that present a skewed image of reality which depicts whites as ever pure and innocent. In another sequence, Baldwin narrates that “when you grow up, you watch the corpses of your brothers and sisters pile up around you” and simultaneously, Peck shows several pictures of present-day victims of police brutality.

He often brings in the historical continuity of violence; spanning from gruesome images of the Wounded Knee Massacre from 1890 and violent clips from several Westerns, to graphic footage of police beatings and arrests during the civil rights era, and the Ferguson protests. This footage is seen as Baldwin narrates his view of the future. For example, Baldwin also discusses Bobby Kennedy’s patronizing claim that in 40 years we might have a black president in America. He states: “Bobby only got here yesterday and he is on his way to a presidency, while we have been here for 400 years”. Adding to this paradox, the next thing Peck shows is a video of Barack Obama, during whose presidency the violence did not decline, but rather resounded with movements like Black Lives Matter coming into existence.

In FOR AHKEEM, Obama’s portrait hangs in a St. Louis high school that the protagonist, Daje attends. We see her with the portrait in the background in one of the strongest visual compositions of the film. Echoing the point that Peck makes with Obama’s image, the directors refer here to the discrepancy between Obama’s presidency and the continually poor condition of black life in America.

While it is Daje’s personal story that is in the foreground, the strong social and political commentary of the hardships of her community is consistently present. At the beginning of the film she mentions “being shot twice” while casually chit-chatting with her friends and we see R.I.P drawings on Daje’s notebooks, commemorating her friends.

As the film evolves, the filmmakers include footage of the media coverage of the urgent protests in Ferguson, pointing out that the murdering of black youth is old news to Daje and the black community. We then see her at school presenting her assignment on the Black Panthers movement, stressing the fact that the movement started as a response to police brutality. The consideration of the future fate of black lives is another point made in this continuum of violence – coming from the intimate parental perspective of Daje, who finds out that she is pregnant and expresses the fear she already feels for her baby boy.

All three films discussed use bold personal accounts of violence, as well as explicit footage in order to re-humanize the victims and add an intimate depth to their stories. They strive to redirect the media’s narrative, the legal system, and even mainstream film production, putting into perspective the historical continuity of violence and throwing a curve ball into the hands of the ones responsible by posing direct questions filled with pride and rage.

“All your buried corpses are now beginning to speak,” said Baldwin in 1963, and we can only add that they should speak even louder today, just as these three skillful documentaries did.