First Day

Evicting History By Adefoyeke Ajao

Open Wound By Archana Nathan

The Enemy Imperfect By Asli Ildir

Up Down Fragile By Christopher Small

Freedom oasis By Héctor Oyarzún

Growing up in the Deep South By Petra Meterc

Before the World Ends By Richard Bolisay

Evicting History

By Adefoyeke Ajao

The architectural masterpieces that dot Abidjan’s landscape take centre stage in Laurence Bonvin’s AVANT L’ENVOL (BEFORE THE FLIGHT, Switzerland), selected for Berlinale Shorts. For 20 minutes, the filmmaker offers an expedition of the current functions of monumental buildings – especially the designs of French architect, Henri Chomette.

The architectural masterpieces that dot Abidjan’s landscape take centre stage in Laurence Bonvin’s AVANT L’ENVOL (BEFORE THE FLIGHT, Switzerland), selected for Berlinale Shorts. For 20 minutes, the filmmaker offers an expedition of the current functions of monumental buildings – especially the designs of French architect, Henri Chomette.

The direction of this film is not immediately evident until a seamless montage of scenes moves from one edifice to another, incorporating visuals that proceed from sign posts to the buildings’ interiors – abstractly linking original use with the current usage and state. Was the condition of the structures a reflection of the current state of Ivorien society? Bonvin leaves this unanswered by focusing more on the inanimate.

With the camera concentrating on portraying the various states of the public structures, human dialogue is rendered negligible. When humans do make an appearance in the frame, they are depicted holding informal interactions within the structures. Thus coming off as passive occupants, indifferent to the surrounding nuances of national heritage, but more in tune with the busy streets of Abidjan (which have more human traffic than the monuments). Instances such as students conducting a prayer session in an empty classroom and a casually-dressed lady slouched at an office reception, while laboriously reading a document are just a few examples of the contemporary appropriation of Abidjan’s historical places.

Bonvin evokes a sense of indifference to historical artefacts through the portrayal of deserted masterpieces occupied by self-absorbed bystanders. Even for someone familiar with Ivory Coast’s turbulent history of coups and rebellion, the director does not entirely give a motivation for the significance of the featured buildings. With the various structures being in partial use or in states of dilapidation, only bats seem to be at home within them, roosting and taking flight as they please.

Nostalgia is fleeting in a country characterised by socio-political upheavals, a prevailing scourge on the African continent. Why would people be concerned with buildings from a glorious past when they have more pressing things on their minds? While structures can serve as a reminder of the past, they seem to offer no refuge from the despair of the present. AVANT L’ENVOL is a subtle reminder of what was and what could have been; the anti-climax of post-independence enthusiasm within the African continent.

Open Wound

By Archana Nathan

Filmmaker John Trengove does not believe in comfortable resolutions. And after watching his debut film, THE WOUND (which opened the Panorama section), one begins to see why.

Filmmaker John Trengove does not believe in comfortable resolutions. And after watching his debut film, THE WOUND (which opened the Panorama section), one begins to see why.

Set against the backdrop of Uk Waluka, a ritual that initiates boys into manhood within the Xhosa people of South Africa, Trengove tells a compelling story about same sex desire, one that is as disquieting as the ritual of circumcision that he opens the film with. “None of us can really know what it can mean to hide a part of yourself at all costs and the kind of violence that that can engender”, he says.

THE WOUND is about an impossible relationship between two young men of the Xhosa community recruited to be mentors of young boys who have just gone through their initiation ceremony. We discover their forbidden love story through the eyes of a boy from the city, sent to the mountains of the Eastern Cape to be turned into a man.

In more ways than one, it is this boy that serves as our entry point into the narrative. And as Trengove admits, the boy often tended to be his voice too. “I knew that same sex desire would be the lens with which I would enter the film. I’m a South African filmmaker, a queer filmmaker, but in the context of the initiation rituals, I definitely was the outsider. And I needed to embrace that fact. I think there is a lot about the ritual that I learnt gradually, but felt that it was really not my place to comment on them. What is not known about the ritual is the transformative effect it has on a lot of men. It helped to have an outsider be my voice,” says Trengove.

An alumnus of Script Station at Berlinale Talents, Trengove plans to release his film in South Africa sometime in the middle of this year and he does anticipate controversy. “The ongoing discussion on Twitter gives a sense of the kind of disparate responses the film is likely to have. It is going to be an interesting year for me”.

The Enemy Imperfect

By Asli Ildir

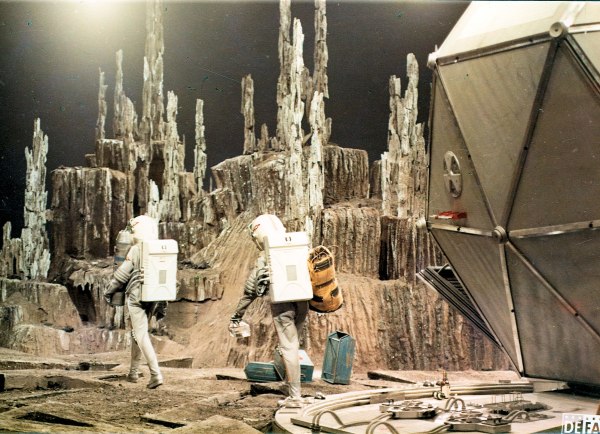

One of East Germany’s hidden treasures, EOLOMEA (Herrmann Zschoche, East Germany) is part of the 67th Berlinale Retrospektive programme “Future Imperfect,” a wide selection of science fiction films from different eras and nations. EOLOMEA premiered in 1972, the same year as Andrei Tarkovsky’s more celebrated SOLARIS, but took a less auteurist and more commercial approach than its Russian contemporary. Looking back 45 years later, EOLOMEA deserves interest by giving a vision of the future imagined within the conditions of the sci-fi genre during the détente period of Cold War era.

One of East Germany’s hidden treasures, EOLOMEA (Herrmann Zschoche, East Germany) is part of the 67th Berlinale Retrospektive programme “Future Imperfect,” a wide selection of science fiction films from different eras and nations. EOLOMEA premiered in 1972, the same year as Andrei Tarkovsky’s more celebrated SOLARIS, but took a less auteurist and more commercial approach than its Russian contemporary. Looking back 45 years later, EOLOMEA deserves interest by giving a vision of the future imagined within the conditions of the sci-fi genre during the détente period of Cold War era.

Moving past the 1950’s “us against other” narratives typified in Hollywood sci-fi films like WAR OF THE WORLDS (1953) or INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS (1956), EOLOMEA takes on the notion of crossing new frontiers. In a future world where human civilization has spread to other planets, the film is built on the mystery around the disappearance of eight space ships during a mission to discover more planets to inhabit. Two scientists, Maria and Tal, are responsible for deciding whether to find or abandon the space ships, while Maria’s cosmonaut lover Dan desperately tries to turn back to Earth. Instead of the “friend or enemy” conflict of Cold War science fiction films, EOLOMEA features its characters listening to each other and learning to communicate, which can be appreciated within the political context of the détente period.

Shot in 70mm, Herrmann Zschoche applies sweeping wide-angle shots to a range of visuals, juxtaposing bright, open beach scenes that take place on Earth with the cold metallic spaceships floating in space. The film uses its non-linear structure to create a sense of nostalgia, telling the story of the love affair between Maria and Dan with humorous flashbacks to their old times on Earth. He also adds some unexplained, abstract interludes between scenes of the past and the present, with imagery that suggests a microorganism changing shape under a microscope, or a “big bang” explosion in the outer space. These contradictory ways to regard the same images summarize the general feeling in EOLOMEA: in a post-Cold War world, seeing and recognizing your enemy is not that easy anymore.

Up Down Fragile

By Christopher Small

Laura Schroeder’s filmic approach in BARRAGE (Berlinale Forum) presents as many obstacles for the inquisitive viewer as it does open-doors and opportunities. Schroeder’s compartmentalisation of her subjects’ bodies – an early scene sees a young girl in the heat of a tennis match spliced into close-ups of hands, arms, and torso – coupled with an overarching feeling of placidity in the way events and emotions dissipate into nothing, eats away at the film’s obvious central tension. She depicts a clash between generations where big feelings are stifled, depression, confusion, and aggression characterise the family members’ interior and exterior lives, and acknowledgement of past trauma is left unspoken.

Laura Schroeder’s filmic approach in BARRAGE (Berlinale Forum) presents as many obstacles for the inquisitive viewer as it does open-doors and opportunities. Schroeder’s compartmentalisation of her subjects’ bodies – an early scene sees a young girl in the heat of a tennis match spliced into close-ups of hands, arms, and torso – coupled with an overarching feeling of placidity in the way events and emotions dissipate into nothing, eats away at the film’s obvious central tension. She depicts a clash between generations where big feelings are stifled, depression, confusion, and aggression characterise the family members’ interior and exterior lives, and acknowledgement of past trauma is left unspoken.

With three generations of women at play, the emotions are either muted or outsized, either understated or bordering on hysteria. And yet, the sudden emergence of big emotion at intervals throughout is almost frustrating; instead of escalating and accelerating the drama, these moments tend to stick in the air, contrasting the otherwise evasive, half-muttered way that emotions play out in this world.

Of course, one could argue that such is life; that in our world as in BARRAGE emotions percolate and erupt inappropriately, are muffled and abbreviated and surrounded by what looks like total calm. But this stop-start sensation of shifting emotional states and, eventually, the introduction of a kind of warped dream level to the film, does not feel like part of an organic or complex design. Schroeder has a remarkable way of letting scenes play out without calling attention to their length; she is sharp when it comes to focusing our attention on one side of a conversation –editing so that sound becomes an integral part of our perspective on key events – and yet never seems like that much of an avowed formalist convinced of the integrity and immutability of her well-composed frames.

It should be enough to say that this light touch and roundabout way of tackling intensity of feeling is refreshing. But in the end one gets the sense that the whole architecture of the project – an intergenerational crisis of parenting and an equally-monumental crisis of struggling to express feelings candidly – is jeopardised by the exquisite ornateness of its images.

Freedom Oasis

By Héctor Oyarzún

“Casa Roshell” is a real club in Mexico City where Roshell Terranova gives “personality lessons”. Men who are afraid of showing themselves publicly as transvestites learn how to dress correctly, wear make-up convincingly, and explore what it means to be a “women” in a safe place. Like in Donoso’s previous film NAOMI CAMPBEL, CASA ROSHELL, challenges social definitions of gender.

“Casa Roshell” is a real club in Mexico City where Roshell Terranova gives “personality lessons”. Men who are afraid of showing themselves publicly as transvestites learn how to dress correctly, wear make-up convincingly, and explore what it means to be a “women” in a safe place. Like in Donoso’s previous film NAOMI CAMPBEL, CASA ROSHELL, challenges social definitions of gender.

The film’s introduction takes an observational documentary approach to Roshell’s transformation process. Donoso makes a slow-paced depiction of a transvestite’s make-up process and films it with an odd blocking that doesn’t let us see her face directly. We see her back from different angles, but all the moments we can see her are exclusively in reflection. When Roshell’s transformation is over we can finally see her taking frontal control of the frame. The shy person who was calmly preparing appears now as a master of ceremony of a secret club.

From this moment on the film takes a leap from observation to a chaotic collage of daily moments that wanders through casual conversation and romantic encounters based on the club’s real events. It is in these casual conversations where Donoso’s political perspective appears. Masculine and feminine qualities are discussed in a place where men presenting as women flirt with “masculine” men. In one conversation, a bisexual asks a straight male, how he can be a heterosexual at this club, to which he answers “but they are women.” This shows that inside “Casa Roshell” social gender rules are absent, and anyone can choose their gender or, as Roshell would say, “their personalities”.

With the highest rate of transgender killings in Latin America, there is severe discrimination and danger in Mexico’s capital, but Casa Roshell deliberately ignores the outside world. Donoso doesn’t speechify on these issues, and shows a different kind of political resistance. It is a film inspired inevitably by a larger world of violence, which it choses to answer through this community based on friendship and freedom.

Growing up in the Deep South

By Petra Meterc

DAYVEON by American director-composer Amman Abbasi is screening in Berlinale Forum and is also cross-sectioned with Generation 14+. It seems as though the director himself wasn’t quite sure whether he wanted to make a slice-of-life art film or a coming-of-age drama.

DAYVEON by American director-composer Amman Abbasi is screening in Berlinale Forum and is also cross-sectioned with Generation 14+. It seems as though the director himself wasn’t quite sure whether he wanted to make a slice-of-life art film or a coming-of-age drama.

The film depicts the 13-year-old boy Dayveon living near Little Rock, Arkansas, who, having lost his brother in a gang-related shoot-out, lives with his sister’s family. He spends his time as most of the boys his age do: riding bicycles, playing video games, scrolling on their phones, smoking blunts. However, in this poverty-stricken rural environment, free time also involves joining a local gang.

The cinematographic portrayal of Dayveon and those close to him, well-executed by DOP Dustin Lane, mixes a documentary approach with a stylized blurring in and out in scenes of movement, as well as playing with natural light by illuminating faces or various interior spaces.

On the other hand, the 4:3 Academy ratio framing works well with symmetrical compositions of bodies in small rooms, as well as with the many close-ups which emphasize the personal perspective that the film adopts. The close-ups often completely cut-out the surroundings and the camera lingers on characters’ faces or even parts of their faces which brings intimacy to these characters portrayed by non-professional actors. Their introspective expressions are highlighted within these everyday scenes.

Rather than the typical depiction of urban gang-violence, refreshingly, Abbasi chooses to focus on teenage gangs within a rural environment. For research, the director workshopped the script with several boys involved in gangs, however the film would have worked better without the all too familiar narrative tropes. There are many clichés that appear in the otherwise casual dialogues, and the melodramatic Yann Tiersen-like piano score feels like Abbasi is instructing us on how to feel. The ongoing metaphor of swarming bees, the interpretation of which preoccupied the audience during the Q&A, didn’t seem to get its point across either.

All in all, the realistic violence and threatening atmosphere together with the poetic cinematography would suffice – they are effective on their own and do not need to be explained through the one-dimensional script which should either be more unconventional or completely minimized.

Before the World Ends

By Richard Bolisay

“The designers of the first atomic bomb were concerned that a nuclear detonation might ignite the earth’s atmosphere and kill every living thing on earth. They went ahead and tested the nuclear device anyway.” This is the first fact about nuclear weapons listed in the programme notes distributed at the Berlinale screening of THE BOMB (Kevin Ford, Smriti Keshari, Eric Schlosser, USA). Such information supplements the harrowing yet completely engrossing experience of seeing it, as the subject relates to dangers of a global scale but one that has been mostly overlooked over the decades.

“The designers of the first atomic bomb were concerned that a nuclear detonation might ignite the earth’s atmosphere and kill every living thing on earth. They went ahead and tested the nuclear device anyway.” This is the first fact about nuclear weapons listed in the programme notes distributed at the Berlinale screening of THE BOMB (Kevin Ford, Smriti Keshari, Eric Schlosser, USA). Such information supplements the harrowing yet completely engrossing experience of seeing it, as the subject relates to dangers of a global scale but one that has been mostly overlooked over the decades.

Initially presented at the 2016 Tribeca Film Festival as a multimedia installation, with floor-to-ceiling screens and live music at the center, the version shown in the Berlinale Special section is a 61-minute film that combines archival footage from countries with nuclear weapons such as the United States, Japan, India, the United Kingdom, and North Korea, from the 1940s to the present. Art-directed by Stanley Donwood, these images are manipulated with incredible attention to detail — small and large texts, numbers and scribbles appear and disappear on-screen — an effect that heightens the emotional heft.

Enriching it further is the live music by the four-piece rock band The Acid, whose layers of sounds provide THE BOMB with a rather soulful quality. With their perfectly timed crescendos and evocative interstices — with simulations of testing and attacks, as though the viewers suddenly found themselves in the middle of a nuclear war and felt its effects — they are crucial to the creation of an overwhelming atmosphere of alarm, one that goes beyond technical innovation and towards something more meaningful: a call for action to look into humanity’s worst crime, and a reexamination of the role of governments to prevent the total destruction of the world.

It is only understandable that with this multimedia work, the three key people behind it come from different backgrounds. Ford is a director, editor, and cinematographer; Keshari is a multimedia artist; and Schlosser is a journalist and writer known for his essays on Hiroshima and nuclear war, and whose book, “Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety”, has inspired the project. With numerous audiovisual elements, its effect is full. More than letting the audience experience the enormity of nuclear technology, THE BOMB displays an emotional core that looks to humans for answers and solutions. It is a strong statement on how this urgent problem can be addressed: there is no way to undo all the harms caused, but only humans themselves can mitigate a looming extinction.