The Talents 2017: Selfies

The Talents 2017: Selfies

Participants at the 2017 Talent Press Workshop, at Berlinale

Adefoyeke Ajao, Nigeria

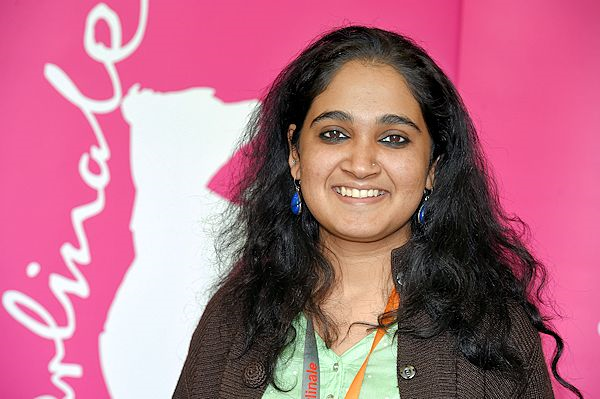

Archana Chidambaranathan, India

Asli Ildir, Turkey

Richard Bolisay, Philippines

Christopher Small, UK

Héctor Oyarzún, Chile

Petra Meterc, Slovenia

Rowan Abdelrahman Ahmed Mahmoud El Shimi, Egypt

Press Pass, Limited Access

By Adefoyeke Ajao, Nigeria

While growing up, I was endeared to film criticism by the cheeky but fair reviews that I read in the British tabloids my father brought home. They made me realise that movies should not be fleeting images targeted at a passive audience, but should instead be instruments of ‘edutainment’ and amenable to critical analysis. Hence, my unconscious urge to assess every film I watch. How best do these films reflect the past and current state of the societies they are trying to depict and what value do they add to the teeming audiences that throng the cinemas and DVD stores just to grab a copy of the next blockbuster?

While growing up, I was endeared to film criticism by the cheeky but fair reviews that I read in the British tabloids my father brought home. They made me realise that movies should not be fleeting images targeted at a passive audience, but should instead be instruments of ‘edutainment’ and amenable to critical analysis. Hence, my unconscious urge to assess every film I watch. How best do these films reflect the past and current state of the societies they are trying to depict and what value do they add to the teeming audiences that throng the cinemas and DVD stores just to grab a copy of the next blockbuster?

Nigeria boasts of a film industry that dates back decades, even if it just earned the sobriquet ‘Nollywood’, about twenty years ago. However, film criticism is still an emerging art, probably because it remains a largely academic field that is usually overshadowed by literary criticism. I use the term ‘emerging’ because despite being a colossal movie industry, Nollywood has been mostly neglected in terms of mainstream scholarly critique accessible in dedicated film columns. Film magazines and full-time critics are few and far between in Nigeria, although the industry churns out films in large numbers and aspires to emulate its foreign counterparts by celebrating its products with glitzy premieres, awards and festivals.

Yet this is changing as media outlets – mostly online – are beginning to dedicate column space to reviews, recaps, and rejoinders from filmmakers. Conversations about films often take place on individual social media profiles or blogs. These developments, to an extent, have reduced the impression of the critic as an antagonist who offers no meaningful recommendation. However, reviews might sometimes bear the tone of commissioned press releases or hatchet jobs that do not adequately engage the work of the filmmaker – raising the problem of objectivity among film journalists.

In addition, the critic is sometimes daunted by constraining factors such as press ownership; the horde of fans who find criticism of their beloved filmmaker unbearable, as well as the wrath of the filmmaker, distributor and commercial cinema management, who regard the critic as an agent of sabotage. Nonetheless, I believe a film critic owes the filmmaker and the average cinephile a fair opinion, withholding such would be depriving these stakeholders of a satisfactory evaluation of the motion picture.

One needn’t have the last word as a critic

By Archana Chidambaranathan, India

India is and has been a cinema-crazy country for years. Whether it is the elaborate rituals that are performed in parts of the country before the release of a film each week, or the numerous fan clubs that adorn the inner lanes of cities where the birthdays of actors and actresses are celebrated with an unimaginable splendour, the life of cinema in India extends much beyond the screen. Growing up, I’ve imbibed and recognised a similar kind of fascination (albeit minus the fanaticism) for cinema within me and gradually saw myself being drawn to study it as well. Writing about a film is an extension of my love for the medium, its potential and its universe.

India is and has been a cinema-crazy country for years. Whether it is the elaborate rituals that are performed in parts of the country before the release of a film each week, or the numerous fan clubs that adorn the inner lanes of cities where the birthdays of actors and actresses are celebrated with an unimaginable splendour, the life of cinema in India extends much beyond the screen. Growing up, I’ve imbibed and recognised a similar kind of fascination (albeit minus the fanaticism) for cinema within me and gradually saw myself being drawn to study it as well. Writing about a film is an extension of my love for the medium, its potential and its universe.

There isn’t one National cinema but many cinemas of India; each region has nurtured its own industry, icons and traditions of filmmaking. Naturally, the scope for discussion and criticism is amplified with a plethora of voices—genuine and PR driven– contributing to the debate about what makes a film work or an industry tick. A critic, therefore, in such a vibrant atmosphere, is one among the many voices contributing to the reception, history and documentation of a film. Often, a critic also introduces one part of India to another, through cinema.

The country is currently going through an interesting phase. Independent cinema in the recent past has gained a larger viewership, financial and cinematic experiments in filmmaking have seen success too. Therefore, film criticism is poised to play an important role: to note, follow and analyse the developments of burgeoning cinemas in the country. But there is a growing need for more honest voices as well.

Last year, in an interview for The Hindu, the publication I work for in India, Peter Bradshaw, The Guardian’s Chief Film Critic said something which stood out for me. He said, “I hate the idea that a critic is reliable.” It is perhaps easy to bask in the self importance and glamour that the role of a film critic brings with it, perhaps even more in the current era of a social media boom. But if there is one skill I would deem is important for a film critic, it would be the ability to not take oneself too seriously. For me, this skill liberates the critic and the writer in her. It paves the way for an unfettered study and analysis of a piece of cinema, perhaps the closest to an honest one as well. It also privileges the film over its critic; the latter is ideally in service of the former.

WRITING ABOUT “A HELL OF A TRUTH”

By Asli Ildir, Turkey

Talking about the national cinema and film criticism in one’s country to an outside audience has always felt impossible to me. Even though I accept a total subjectivity in my words, I doubt the truth of my own subjectivity, too. This becomes more problematic when it is the global “East,” which Turkey is a part of, that needs to be explained. The hazards of orientalist and self-orientalist tendencies in both film criticism and filmmaking and the burden of the political “realities” and the desperate endeavor to represent those realities “properly” with the limited financial resources are the ongoing curses and limitations that makes the creative industry timid and withdrawn. A scene from a recent film from Turkey called Why Can’t I Be Tarkovsky? (2014) by Murat Düzgünoglu teases out this dilemma Turkish cinema faces in one of its scenes. A filmmaker who has to shoot commercial films for a living tries to get funding from the European Film Foundation for his screenplay. His girlfriend advises him to shoot something about the “West and East relations, cultural amalgamation or refugees” in order to get funding and to be realistic about his own ideas. There is an ongoing clash between the expectations from the movies or criticism of movies in Turkey and the actual creative purposes, or agenda in the film industry in Turkey.

Talking about the national cinema and film criticism in one’s country to an outside audience has always felt impossible to me. Even though I accept a total subjectivity in my words, I doubt the truth of my own subjectivity, too. This becomes more problematic when it is the global “East,” which Turkey is a part of, that needs to be explained. The hazards of orientalist and self-orientalist tendencies in both film criticism and filmmaking and the burden of the political “realities” and the desperate endeavor to represent those realities “properly” with the limited financial resources are the ongoing curses and limitations that makes the creative industry timid and withdrawn. A scene from a recent film from Turkey called Why Can’t I Be Tarkovsky? (2014) by Murat Düzgünoglu teases out this dilemma Turkish cinema faces in one of its scenes. A filmmaker who has to shoot commercial films for a living tries to get funding from the European Film Foundation for his screenplay. His girlfriend advises him to shoot something about the “West and East relations, cultural amalgamation or refugees” in order to get funding and to be realistic about his own ideas. There is an ongoing clash between the expectations from the movies or criticism of movies in Turkey and the actual creative purposes, or agenda in the film industry in Turkey.

Film criticism does not have any financial support from the Turkish government, and unfortunately, it also doesn’t have a wide audience. Lack of financial support and interest has lead film critics to establish their own independent magazines. This opened up space for more free thought and an inclusive policy regarding Kurdish, Armenian, queer and feminist cinema, and therefore politicized the content, too. I consider film criticism as a crucial philosophical inquiry into the perception and interpretation of movies in their context. Especially in Turkey, which has been in a political crisis since the beginning of 2016 including a lot of violence toward filmmakers, academics, journalists, students, and politicians, it has become a place where there is an epistemological transition in intellectual discussions and daily conversations. Everything is politicized in chaos. This politicization, which may be considered a way of coping with the political trauma, is pregnant with dangerous political consequences, a widening polarization. The perception of the movies, especially the movies that are necessarily politicized in the post-2010 period is crucial because the proper representation and interpretation of the contemporary atmosphere has the possibility to bring some kind of balance, a moment of breathing, a space for contemplation. Experiencing and observing the artistic inquisitions, and trying to understand the historical moment through cinematic moments are what made me a film critic.

Being a Film Critic from the Philippines

By Richard Bolisay, Philippines

I live in Manila, the capital of the Philippines, a country whose historical and cultural richness and diversity offer countless stories to its artists. Burdened by centuries of colonial rule and currently by neocolonialism, the Philippines itself — with its thousands of islands, and thousands of traditions — has always been a strong reason for my love of cinema. In every article I write there is an unconscious, yet not unnatural, attachment to this country I call home, and my path as a film critic has been defined by it. Over the years, my purpose has become clearer: to promote our national cinema and develop a better understanding of it.

I live in Manila, the capital of the Philippines, a country whose historical and cultural richness and diversity offer countless stories to its artists. Burdened by centuries of colonial rule and currently by neocolonialism, the Philippines itself — with its thousands of islands, and thousands of traditions — has always been a strong reason for my love of cinema. In every article I write there is an unconscious, yet not unnatural, attachment to this country I call home, and my path as a film critic has been defined by it. Over the years, my purpose has become clearer: to promote our national cinema and develop a better understanding of it.

I am a graduate of Film and Audiovisual Communication from the University of the Philippines — the finest local institution that offers an extensive and intensive study of film, to which I owe the foundation of my writerly pursuits. Like many universities, it is unapologetically filmmaker-centric: you study film to make films. And that’s sad because I belonged to a small group that sees the significance of criticism, especially since this field is often overlooked and under appreciated, financially and professionally. There is a stigma to being a film critic, and one can easily notice the scarcity of people in the past and present who pursued it. Clearly, we don’t have a strong culture of film criticism. Despite the rise in the number of movies produced because of digital technology, not much has improved in terms of film studies — we still have fewer platforms and opportunities for writers and critics.

This is a shame because Philippine cinema has always been a rich source of discussion: from the constant concerns with art and entertainment, as well as mainstream and independent production, the problems with accessibility and distribution, the growing number of local festivals, the proliferation of and fascination with love teams, the development of an audience receptive to bolder narratives, the importance of alternative screening venues, to the stories that come from different parts of the country, forming a complex, multifaceted identity covering not just poverty, survival, nationalism, religion, freedom, and dissent, but also a whole stream of varied personal, cultural, and political issues — all specific to us. As a film critic, providing a well-rounded perspective on Philippine cinema is my priority, and my work for almost ten years as a writer, editor, programmer, lecturer, jury member, and selection committee member has given me knowledge and experience to represent it as best I can.

The State I am In

By Christopher Small, UK

By Christopher Small, UK

My country has been under the grip of austerity for more than six years. The UK Film Council was disassembled shortly after our centre-right government took the reigns of power. Our national cinematheque, the BFI Southbank, has been slowly pulped and tenderized by our government’s vast slashing of state-sponsored arts programmes. I’m told that a vibrant, diverse, bountiful place for cinephiles to congregate in communities has been massively reduced in scale. As is the story in many European, state-funded cinema museums, the funding is drying up. Though it’s still a special place, the big events that now dominate the schedules leave little room for discovery.

There is little choice but to seek these things abroad, to reclaim cinema as an international pursuit, to undertake an annual pilgrimage to lands with richer cinematic soil, as well as cheaper drinks, than the United Kingdom. What does this lead to? Cinema as a private obsession, as an expensive holiday in an exotic land, as an alternative to reality? Does this make the idea of taking film seriously something only possible in elite outposts distant from the world of jobs, friends, pets, bills, family?

Perhaps. But an unlikely consequence of all this depression and reduction is that the cinema has become, to me, private and international, simultaneously. The internet too, with its colossal reach, unites the disparate private worlds of critics, as well as the communities that coalesce around certain films and filmmakers and, in a certain sense, makes it easier to connect when the opportunity comes to forge connections in person.

Being a critic has its bonuses. I consider person-to-person connection vis-a-vis movies the most important thing about writing about film, other than maybe seeing the film and meeting your deadline. I have learned more about film criticism in person from these people—met largely at film festivals—than in any other environment, including film school. Being a critic also lets me see more movies for free; this is perhaps the best excuse I use to justify the truly dismal pay involved.

But I am a critic because I like movies. The day I stop being interested in the way films make me feel, and in the ideas they propose, is the day I will lay down my pen. I am also a writer: I get pleasure from the material act of translating my thoughts into words, filtering them through a vocabulary and a syntax that I consider worthwhile and interesting in and of itself, though there are certainly many egotistical benefits to living inside my own head as well.

Reconstructing memories

By Héctor Oyarzún, Chile

My decision to become a film critic was always driven by how I conceive cinema in my country. Chile had one of the most prolific cinematic movements between 1964 and 1973, but it was suddenly cut by president Allende’s assassination. After our USA-financed coup d’État, our brand-new dictator Augusto Pinochet disappeared and tortured dissidents, and then tried to disappear any trace of culture that was seen as “Marxist”. Millions of books were burned, and Allende’s cultural project went up in flames. Literature had this symbolic destruction, yet cinema had a quieter one. Our main filmmakers were sent into exile, and the ones who remained were forbidden to shoot. Our nascent film culture disappeared, and the 70s and 80s saw an incredibly low number of films released in Chile.

My decision to become a film critic was always driven by how I conceive cinema in my country. Chile had one of the most prolific cinematic movements between 1964 and 1973, but it was suddenly cut by president Allende’s assassination. After our USA-financed coup d’État, our brand-new dictator Augusto Pinochet disappeared and tortured dissidents, and then tried to disappear any trace of culture that was seen as “Marxist”. Millions of books were burned, and Allende’s cultural project went up in flames. Literature had this symbolic destruction, yet cinema had a quieter one. Our main filmmakers were sent into exile, and the ones who remained were forbidden to shoot. Our nascent film culture disappeared, and the 70s and 80s saw an incredibly low number of films released in Chile.

After the dictatorship was over, Chile re-constructed its film history piece by piece, but in the 90s, Chile didn’t return to its past glory; it wasn’t so different from our previous decades.

But now, after all this time, it seems that Chile has renewed its interest in cinema. Chile is finally struggling with its demons through cinema. Last year, we saw this historically homophobic country release films such as Rara (Pepa San Martín) and Nunca vas a estar solo (Alex Anwandter), our failed educational system was put on trial [?] in Si escuchas atentamente (Nicolás Guzmán) and El primero de la familia (Carlos Leiva), and directors such as Pablo Larraín and José Luis Torres Leiva are constantly talking about memory in their films.

While cinema has renewed its symbolic power, film criticism is a little bit behind. Film criticism in Chile is not on the same path as our new cinema. These new films are making a political statement through cinematographic language, while our criticism is constantly ignoring which technical aspects can turn a film into a political statement. Criticism should be capable of building bridges and should try to discover where our films are guiding us. This is why I think criticism is important on Chile. These films are talking about our present, but our criticism is not making links between them. After a long time, Chile is reconstructing its lost cinematic culture, and this reconstruction should touch all fields, including how we think about film. Criticism is a way to present the bigger picture, a way to see what art is telling us.

The self-invention of the non-existent profession

By Petra Meterc, Slovenia

It was always about the storytelling. From early visits to the local library as well as the local video shop, the urge to discover different realities through media has stayed with me. I kicked off my work as a journalist writing about literature, and although I have made a gradual crossing into reflecting my cinephilia through film criticism, books have always been there. I believe it is reading, be it fiction or theory that pushes you to evolve in writing. With cinema, I seek to be an independent curator of the viewers’ interests. My focus is in the non-western, independent authors that create on the margins of the mainstream and well-established (either commercial or arthouse) milieu of cinema. Presenting and inviting people to discover other voices, while also inevitably trying to depict the wider, often political context (in content, not in topic), places me within the cinephile criticism with a slight inclination towards film and other theory.

It was always about the storytelling. From early visits to the local library as well as the local video shop, the urge to discover different realities through media has stayed with me. I kicked off my work as a journalist writing about literature, and although I have made a gradual crossing into reflecting my cinephilia through film criticism, books have always been there. I believe it is reading, be it fiction or theory that pushes you to evolve in writing. With cinema, I seek to be an independent curator of the viewers’ interests. My focus is in the non-western, independent authors that create on the margins of the mainstream and well-established (either commercial or arthouse) milieu of cinema. Presenting and inviting people to discover other voices, while also inevitably trying to depict the wider, often political context (in content, not in topic), places me within the cinephile criticism with a slight inclination towards film and other theory.

It is mostly self-taught criticism that is produced and read in Slovenia, with the editors having too much work with the formal and technical part of publishing while lacking time for real mentorship or rigorous editorial process. The only other approach falls into the domain of short texts merely filling the cultural pages of magazines or newspapers, usually devoid of any actual critique or in-depth reflections. Of course, as almost everywhere else, none of us are only film critics; the precarious freelance work not only means that all of us multitask to make our living, but there are also only a handful of real experts to learn from. Slovenia has no film education in its educational system and there is no film studies in higher education, which means that both the viewers, as well as the critics, lack knowledge of film history, theory, and discourse. Luckily, the situation is changing for the younger generations due to the energy of several small organizations carrying out film education projects through various platforms.

Slovene filmmakers produce five to ten features a year, and although in the eyes of the Slovenes, contemporary Slovene film is often stereotypically regarded as too rigid and stuck in search of its identity, there are always authors, from feature to documentaries, as well as animation, that definitely defy those pessimistic generalizations. As for myself, I wish to see more such defiance, not only in filmmaking, but also in the work of the critics. Let us keep re-inventing our profession; after all, its existence seems similarly elusive and fluid like the moving picture itself.

Film criticism in Egypt: Observing blossom out of challenge

By Rowan Abdelrahman Ahmed Mahmoud El Shimi, Egypt

Egypt has a long standing cinema industry. It is one of the oldest in the world and is the oldest in the Arab region and Africa. While Egyptian cinema flourished in local and regional production and distribution from the turn of the nineteenth century until the 1950s, it was largely monopolised by the state for nationalist purposes to establish Egypt’s new modernist socialist state in the 1950s and 1960s. The decades that followed saw a wave of realist cinema capturing stories from the margins of society. Since then the industry has largely fallen victim to several economic crises affecting both the quality and quantity of films produced – that’s not to say there weren’t several shining productions in the past decades.

Egypt has a long standing cinema industry. It is one of the oldest in the world and is the oldest in the Arab region and Africa. While Egyptian cinema flourished in local and regional production and distribution from the turn of the nineteenth century until the 1950s, it was largely monopolised by the state for nationalist purposes to establish Egypt’s new modernist socialist state in the 1950s and 1960s. The decades that followed saw a wave of realist cinema capturing stories from the margins of society. Since then the industry has largely fallen victim to several economic crises affecting both the quality and quantity of films produced – that’s not to say there weren’t several shining productions in the past decades.

There is a long history of film critics observing and commenting on Egyptian films and the industry’s development. An official university programme that trains critics in Cairo, as well as established publications that offer space for their writing has paved the way for several generations of critics, who have their own association. However, film criticism circles are not bound by these academic credentials. Workshops and field learning account for most of the education young critics in Egyptian cities are exposed to.

Currently, the industry is largely shaped by comedies and crowd-pleasers. However, there are several significant contributions from filmmakers and producers in both the commercial and independent realm. While most do not enjoy commercial success at home, they receive wide critical acclaim and hefty festival runs abroad. Yet ongoing issues with both film censorship and restrictive legal conditions on production has made making films a challenge for artists within the commercial and independent industry in Egypt.

These restrictions tend to make film critics serve not only as commentators on the art form, but advocators of a certain plight of freedom of expression – both for themselves and the filmmakers they engage with. Social media has also played a role in creating more channels for film criticism beyond the traditional newspapers, whether through online media, film centred blogs, youtube channels or simply Facebook posts. These platforms have supported the creation of a whole wave of young critics eager to reach the public and are slowly establishing themselves within the industry.

This is where I find much of my writing pivoting: in a space between critical engagement with the films themselves and dealing with topics related to censorship, access to knowledge, centralisation of the industry and festival management. It really boils down to telling the stories of these artists who, in spite of their challenging environment, create their own communities and initiatives to bring their films to light.